Nuremberg, the latest film by James Vanderbilt – yes, the writer-director is a scion of that distinguished East Coast dynasty – contains two lead performances by Oscar-winning actors. One is extraordinary, and the other is extraordinarily bad. Yet it is a sign of how Russell Crowe and Rami Malek’s respective careers have developed over the past few years that were you invited to pick which actor is capable of greatness, and which one has descended into bizarre self-parody, it would not necessarily be easy to pick which one was which.

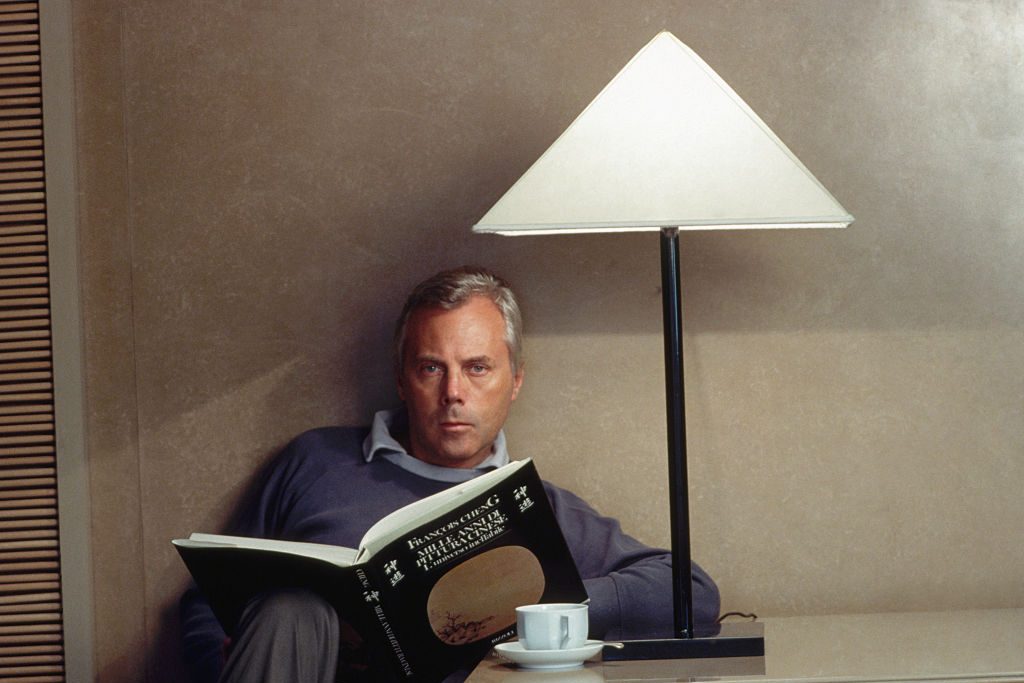

I shall put you out of your misery. In Vanderbilt’s carefully judged and largely successful recreation of the politicking and drama of the post-World War Two Nuremberg trials, Crowe gives his best performance in at least a decade, and probably longer, as Hermann Göring, the senior surviving Nazi who was put on trial for crimes against humanity by the Allies in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat. Crowe has often been a variable actor, given either to laziness or ham, but here he is focused, intense and remarkably effective as Göring, choosing to underplay the part and avoiding grandstanding in the process.

He skillfully suggests what a fascinatingly complex character the German was, and without remotely playing for sympathy or cheap emotion, conveys the sense that he may have been the greatest adversary that the Allies faced. There are points where Crowe, bulked up and dominating the frame, is giving a performance every bit as good as his seminal work in The Insider and Gladiator, and under normal circumstances, this would be a performance that would be getting serious awards attention shortly.

The reason why it probably won’t is, ironically enough, Malek. It is now obvious that his Oscar win for his Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody was both a fluke and unfair; it created a series of expectations that his increasingly arch and stylized performances have failed to live up. Playing the psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who is charged with appraising Göring’s fitness to stand trial and whether he is sincere in his claims that he was unaware of the full horrors of the concentration camps, Malek has a tricky role, but while a dozen other actors could have done something interesting, even affecting, with the part, he falls into his usual retinue of tics and twitches. There were several points that I thought that this was going to turn into something fascinating – Kelley going full American History X – but in the end, I realized it was just a miscast actor doing a poor job, and being hopelessly outclassed by a veteran pro in the process.

This inequality between the two stars means that the picture, which is never less than gripping and interesting, has a strange enigma at its core. Göring is shown, in Crowe’s carefully nuanced performance, to be entirely plausible and several steps ahead of his Allied persecutors, most notably in a (true to life) courtroom cross-examination scene in which he makes Michael Shannon’s stolid prosecutor Robert H. Jackson look complacent and ill-prepared, throwing his questions and accusations back at him and seizing a final opportunity to promote the glory of Germany under the Führer.

The film wants us to be shocked by Göring’s arrogance and self-importance, and to take the side of Leo Woodall’s sweet-natured young translator, Howie Triest, who is eventually revealed to have a very personal animus against the Nazis. Vanderbilt even includes real-life newsreel footage of the concentration camps, which is still nearly impossible to watch, even with all the distance of time, and by the end, as we watch the fascists wet themselves as they hang, we are tacitly invited to see justice being done.

Göring, of course, committed suicide by cyanide capsule before such an indignity could befall him, and it is a mark of the strange ambivalence that Nuremberg leaves us with that Kelley’s comment about his death – “He escaped” – could be seen either to connote anger at his cheating justice or a strange kind of admiration at the larger-than-life, Luciferian figure who dominates the film just as he dominated Germany. For a film so alive to issues of fascism and contemporary relevance – somewhat ham-fistedly expressed in a clumsy, Malek-led coda – it is unfortunate, if inevitable, that the abiding feeling the viewer is left with is as much sympathy for the charismatic devil at the film’s heart as it is horror at the actions of the regime that he was so much a part of. Still, three cheers for Crowe; let us hope that similarly superb performances await in the future, too.

Leave a Reply