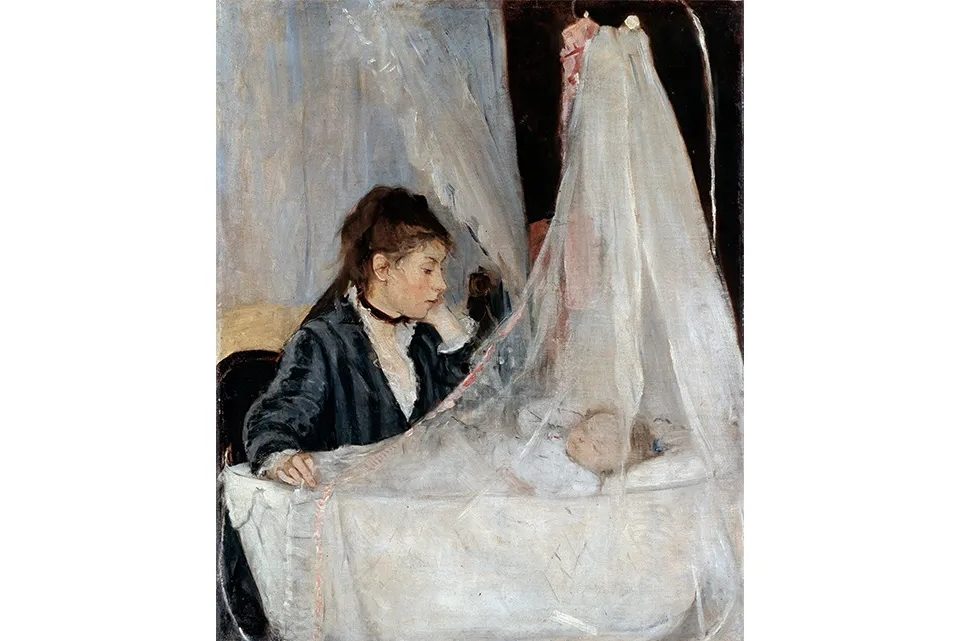

She appears in one of the most beloved paintings in Washington’s National Gallery of Art — “Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl” (1862) — but few people know her name. No longer. Joanna Hiffernan is now at the center of The Woman in White, an exhibition at the NGA that explores the close working relationship between James McNeill Whistler and his Irish model and mistress that produced some of the most beautiful and enigmatic paintings of the 1860s.

“The White Girl” is a haunting full-length portrait of a young woman, with large blue eyes and Titian-red hair, in a white linen dress. She stands on a rug made from the pelt of a wolf (or is it a bear?) and stares off into the distance, while the animal’s taxidermized head, tinged with red pigment, confronts the viewer head-on. A wilted lily dangles from her ringless left hand. The work seems charged with symbolic meaning, but as to precisely what it represents, nobody can agree.

The painting was first shown at an independent gallery in London, which advertised it as “The Woman in White,” a reference to the popular Wilkie Collins novel of the same name. (The plot revolves around a mysterious woman who is revealed to be an asylum escapee.) But Whistler insisted that he had never read the book and that the painting “simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain.”

That didn’t stop critics from trying to decode the work when it reappeared in Paris at the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Is the girl a bride or a fallen woman, they wondered. A sleepwalker or an apparition? A mad, flower-strewing Ophelia or a guilt-ridden Lady Macbeth? The identity of the model remained as inscrutable as the painting’s subject.

The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler reflects a wider movement among historians to portray models as active collaborators in the artistic process rather than silent, passive muses. In recent exhibitions around the world, flame-haired “stunners” like Lizzie Siddal and Fanny Cornforth, the working-class women who posed for Dante Gabriel Rossetti and other Victorian painters, have gotten their due. Yet until now, Hiffernan’s life remained relatively unexamined.

Born in 1843 to a schoolmaster in Limerick, a four-year-old Hiffernan and her family were among the hundred thousand Irish who immigrated to London during the Famine. The conditions in the city, especially for the working poor, were hardly an improvement — records show that her youngest sibling died of malnutrition. By 1860, however, Hiffernan was living in her own studio apartment and likely earned decent wages as an artist’s model.

That year, aged twenty-one, she met Whistler, a twenty-six-year-old American painter. A West Point dropout, he had spent the last few years studying art in Paris, where he began to develop the idea that art should not rely on moral, historical or literary subjects. “As music is the poetry of sound,” he later wrote, “so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of color.”

Whistler was struck by Hiffernan’s beauty and lively personality. The unmarried couple moved in together and embraced their status as outsiders, mixing with longshoremen and sailors, whom Whistler sketched and painted, and attended séances with Rossetti. Whistler trusted Hiffernan with a variety of business matters, and when he undertook a seven-month trip to Valparaíso, Chile, in 1866, he even gave her power of attorney.

Modeling itself was no easy task: the artist was famous for making his subjects work punishing hours. In Whistler’s case, it could also be life-threatening. To create the “Symphonies in White,” a trio of paintings including “The White Girl” that featured Hiffernan in a pale gown, he used large amounts of lead white paint. The toxic fumes made both of them so ill Rossetti, perhaps only half-jokingly, speculated it was lead poisoning that fueled the artist’s “combative” personality.

Whistler and Hiffernan’s romantic relationship deteriorated sometime in the late 1860s, and in 1870 he had a brief affair with a woman called Louisa Fanny Hanson, who bore him a son. (Whistler would later describe the child as an “infidelity to Jo.”) Hiffernan, now referred to as “Auntie Jo,” and her sister, Agnes, brought up the young Charlie Hanson. Hiffernan succumbed to bronchitis at the age of forty-four during a particularly bad winter in 1886, fading from the historical record as quickly as she appeared.

So, alas, further biographical information that might flesh out this “fiery” Jo is scarce. But if the visual evidence on view at the National Gallery is any indication, at least audiences can still rightly exclaim, as Whistler once did, “She has the most beautiful hair that you have ever seen!”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.