In the summer of 1961, Clyfford Still packed his family into a car and began driving south from New York City in search of a new home. In the Forties, Still had shocked audiences with monumental canvases covered in stormy walls of thick, dark, pigment: some of the first totally abstract paintings shown in New York. Subsequently Still had risen with the Abstract Expressionists to unprecedented heights of institutional and commercial success. But despite wielding profound influence as a founding dean of this New York School, torch-bearing wasn’t really Still’s thing.

The independent spirit who Jackson Pollock said ‘made the rest of us look academic’ became a fierce critic of the Manhattan art world, and especially its flourishing contemporary market, which he believed to have a corrupting effect on serious painting. By the early 1950s, Still had stopped working with galleries altogether. He became increasingly notorious for his hermetic detachment from critics, dealers and even fellow artists. Quitting New York entirely was the natural next move.

About four hours down the road, Still stopped in Carroll County, Maryland, a bucolic farmland country 40 miles northwest of Baltimore. The next day, he bought a house with a barn that he could convert into his painting studio. Free from city noise and careerist distractions, Still lived and worked in Maryland for nearly two decades, making painting after painting. For much of this time, few knew what kinds of pictures the reclusive artist was creating in that converted barn; many canvases have only recently been unrolled, stretched and catalogued. He continued to exhibit only rarely, selling just enough work to get by, and was extremely hesitant to place works in museums, donating to just four in his lifetime, usually with severe restrictions.

Still’s vise-like grip on his art and its presentation puzzled and exasperated many. His alertness to the eternal threat of art-world dirty dealing, however, was vindicated in October, when the Baltimore Museum of Art, one of those happy few institutions he gave to, shocked the art world by announcing that it would be selling his gift.

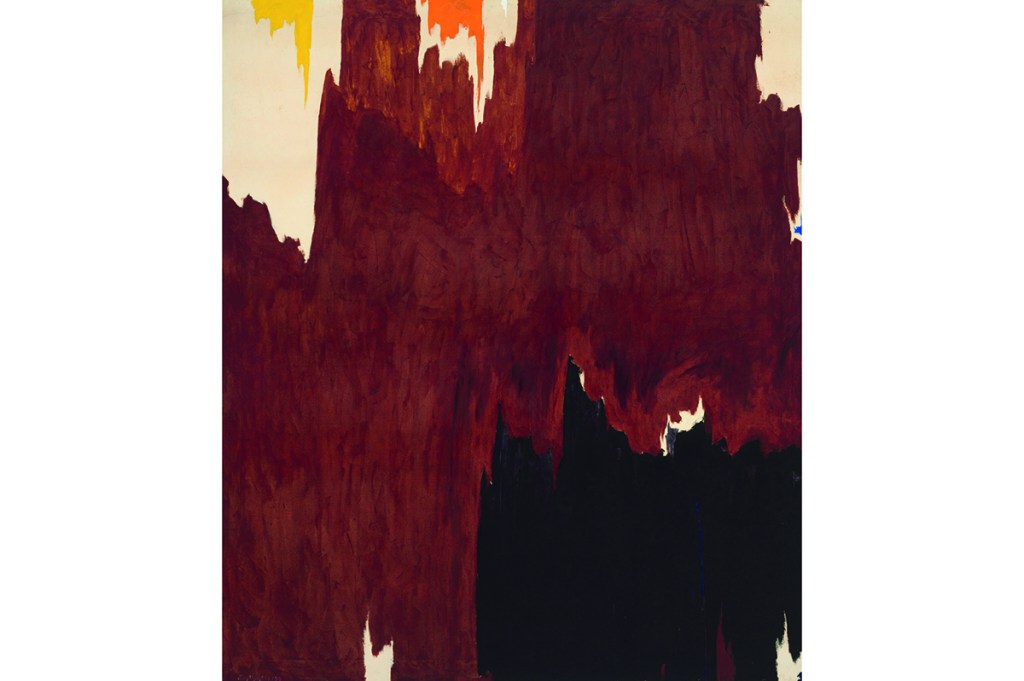

Titled ‘1957-G’, the huge painting — nearly nine by eight feet — is an unquestioned classic. Still’s signature dynamic forms predominate in rust red and black, while smaller flashes of orange, yellow, blue and white shoot out from the top and right edges. The Baltimore Museum’s decision to sell Still’s gift, along with a ‘Last Supper’ by Andy Warhol from 1986 and a large abstraction by Brice Marden from 1992, ignited a firestorm of national debate.

The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) stated its intention to use the expected windfall of $65 million ‘to help advance salary increases across the board, invest in diversity and inclusion programs, offer evening hours and eliminate admission fees for special exhibitions’. Righteous and admirable as these operational objectives may be, liquidating artworks to fund them would typically be unimaginable for a major collection. The Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), the museum world’s professional oversight organization, has strict rules, and threatens sanction, against ‘deaccessioning’ for reasons other than securing the capital to purchase new art. This spring, however, the AAMD, anticipating extraordinary financial difficulties as a result of the interminable COVID-19 lockdown, relaxed its guidelines.

The BMA, while cheerfully maintaining that it was not in financial trouble, chose this moment to offload three treasures from its collection of 20th-century modernists. Other museums also suddenly jumped to move masterpieces. By late October, the Brooklyn Museum had sold 16 works by Cranach, Corot, Courbet, Monet, Matisse, Miró, Degas and others. The Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York pawned its only Pollock. The Palm Springs Art Museum in California dumped a massive 1979 painting by one of Still’s Abstract Expressionist colleagues, Helen Frankenthaler. Museums in Indianapolis, Fort Worth, Montclair, Laguna Beach and Springfield also put works from their so-called ‘permanent collections’ on the auction block.

The magnitude and cynicism of the Baltimore Museum’s artistic offloading was outrageous even in this season of nationwide sell-offs. The museum, led by its board of trustees and its ambitious director, Christopher Bedford, appears to have chosen the Still, the Warhol and the Marden because of their enormous commercial values. This seems to violate the AAMD’s standing directive not to ‘capitalize or collateralize collections or recognize as revenue the value of donated works’. Rather, the chief criteria for deaccessioning should be works’ poor quality, redundancy or relative unimportance within the overall collection, for instance ‘a duplicate that has no value as part of a series’.

The BMA attempted arguments for each work’s redundancy, but these, as the art historian Martin Gammon wrote in the Art Newspaper, ‘don’t come close to passing the smell test’. The Brice Marden is the BMA’s only painting by the 82-year-old artist. Still’s ‘1957- G’ is the BMA’s only work by perhaps the most important painter ever to work in Maryland. The ‘Last Supper’, made just months before Warhol’s death, is far and away the most important piece by him in the museum’s collection. All three were on more or less permanent view in the museum’s galleries: the BMA’s own curators believed these works to be important elements of its collection, central to its 20th-century holdings, and not at all redundant — until suddenly they were.

Christopher Bedford’s justification for dumping the Clyfford Still was egregious. Bedford advanced a definition of redundancy so loose as to be arbitrary: redundancy, he claims, should focus ‘more on the broader narration of art history than on focusing on one particular artist’. For this, read: Still is expendable because we hold other Abstract Expressionist paintings by other white men of the time. Has the director ever actually looked at the artworks in his collection? It’s tremendously easy to pigeonhole paintings through the delimiting categories of the politicized historian — period and place, but above all race and gender — but much harder to grapple with artworks as unique creations, each expressing an individual vision.

The proposal to sell Still’s gift was all the more baffling given the director’s almost brotherly relationship with Mark Bradford. Bedford has championed Bradford as perhaps the most significant artist of our own time. He has curated Bradford exhibitions not only at the BMA, but also for the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale of 2017. Yet Bradford, who happens to be black, has repeatedly acknowledged Clyfford Still, who happened to be white, as a crucial artistic influence. In 2016, Bradford even curated a show that examined his debt to the mid-century painter. Consigning the Still to an almost certain future in some billionaire’s private viewing room would thus rob Baltimoreans of their right to see Bradford in the full context his art deserves. Most disastrously, it would eliminate the chance for young Baltimore artists to develop similarly inspiring relationships with masterpieces from decades past. I recall challenging encounters with these very artworks during my countless trips to the museum as an aspiring painter. Cutting Still’s link to Baltimore and Bradford’s link to Still is not likely to advance the BMA’s stated goals of serving as a resource for Baltimore’s minorities and economically disadvantaged.

Thankfully, voices across the country rose up to oppose this mass privatization of Baltimore’s cultural patrimony. Christopher Knight, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Los Angeles Times art critic, even eviscerated the BMA’s leadership in his weekly column:

‘The sleaze is almost too hard to wrap your head around… Baltimore’s leadership, in a sordid display that conjures the cold opportunism of disaster capitalism, exploited the deadly health crisis to raid the storerooms… The Baltimore Museum of Art is now the leading poster child for art collection carelessness…’

Black artists Amy Sherald (an art world superstar since her official portrait of Michelle Obama was unveiled in 2018) and Adam Pendleton resigned from the BMA’s board. A group of former trustees and curators wrote a letter to the Maryland Attorney General, asking him to investigate the sale. Two former board chairman canceled planned gifts totaling $50 million, and one demanded that his family name be stripped from the museum’s walls.

Emboldened, no doubt, by this national outcry, the AAMD wrote to its members. The letter, clearly aimed at the BMA but without naming names, warned that the AAMD’s relaxed guidelines for deaccessioning ‘were not put in place to incentivise [sic] deaccessioning, nor to permit museums to achieve other, non-collection-specific, goals’.

Bedford and the BMA’s trustees stood firm, reiterating their intentions — and, outrageously, challenging their critics’ dedication to justice and equality. But the next day, after 15 former directors of the AAMD — all leaders of some of the country’s most prominent museums — had weighed in and directly urged the BMA to reconsider, Bedford and the trustees finally relented. Hours before the works were set to hit the block at Sotheby’s in New York, the museum announced it would ‘pause’ its plans to sell.

The BMA talks of postponement, not cancellation, while it holds ‘further, necessary conversations’, but it also maintains that ‘our vision and our goals have not changed’. It’s unclear if the museum still hopes to offload the paintings once the outcry has died down. The hammer may yet fall on the block at Sotheby’s. If it does, it would be to Baltimore and Maryland’s shame. But the blow won’t only land on the people of Baltimore: the American public everywhere will pay for the crushing of standards and the pulverizing of collections for short-term gain.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2020 US edition.