This article is in

The Spectator’s November 2019 US edition. Subscribe here.

To gauge a man’s character, note how he spends a month in Paris. Edward Hopper, according to the catalog of his 1933 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, lodged with a ‘respectable French family’, studying French and ‘avoiding bohemia’. Asked if he met any painters during his visits, he responded, ‘No, I did not know anyone. Gertrude Stein was on the throne when I was there.’ Hopper knew it wasn’t his scene.

Isolation was a persistent theme in Hopper’s art and life. Was he dogged by isolation or did he pursue it? ‘Did anybody really know this silent, non-communicative man?’ asked Raphael Soyer in a 1981 interview, 14 years after Hopper’s death. His friends recollected a cynical and taciturn artist, self-doubting, introspective and distrustful of fame. But before Hopper became the painter of lonely figures in all-night diners, he was the illustrator of raucous party scenes and smiling couples waltzing together at summer fêtes.

Edward Hopper and the American Hotel, a rich exhibition now at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, highlights the contrast between Hopper’s early, lesser-known years as a commercial illustrator and his later eminence as laconic American icon, the serious solitary who painted crumbling Victorian boarding houses, faded hotel lobbies and highway motels.

Born in Upper Nyack, north of New York City, in 1882, Hopper lived in Greenwich Village most of his life, but regularly sought solitude in road trips across the US and Mexico, accompanied only by his wife Jo. He often painted from the viewpoint of an outsider looking in: the transient nature of travel placed him in his natural element. In a hotel, each guest is a stranger to the others, suspended between destinations and unmoored from past circumstances. From the leather-upholstered comfort of a car, pathos-rich scenes and structures fly by like pies in a revolving case.

Hopper graduated from art school as the Gilded Age began to tarnish. He found work as a commercial illustrator for trade publications like Hotel Management and the Waldorf-Astoria’s in-house magazine, Tavern Topics. On his magazine covers, men and women indulge in every stereotype of Gatsbyesque leisure. These happy, glamorous creatures are a far cry from the lonely souls of his painterly world. The contradiction is almost indecent enough to make you demand your admission fee back.

Hopper later disdained his time as an illustrator — Jo called it ‘doing the dishes’ — yet it left an indelible mark on his style. Needing to communicate persuasively and to attract customers as they walked past a newsstand, he created cover illustrations with strongly lineated forms and figures. He carried these razor-sharp silhouettes and compositions into his painting career.

In 1924, Hopper quit commercial illustration to devote himself to oils and watercolors. His first hospitality-themed painting, 1931’s massive ‘Hotel Room’, is a stripped-down antithesis of his Waldorf-Astoria scenes. In a closet-sized room, a half-dressed woman slumps over a yellowed train timetable. The sterile light from a ceiling lamp leaves her face in shadow. Nearby, her cloche hat is a reminder of the public persona she’ll assume before leaving for her next destination. It’s an intimate scene of unguarded solitude, but it resists a specific narrative.

One day, Jo described Hopper’s 1950 canvas ‘Cape Cod Morning’ back to him as ‘a woman looking out to see if the weather’s good enough to hang out her wash’. Hopper rejected this reading: ‘Did I say that? You’re making it Norman Rockwell. From my point of view, she’s just looking out the window.’ Hopper explicitly avoids sentiment and social messages; he had studied with Robert Henri, a co-leader of the realist Ashcan movement, who espoused depiction without adornment or Victorian moralizing. A hotel room is just a hotel room, except when it’s a dazzling study of color.

Hopper’s greatest interest was the rendering of light, yet he sneaked saturated hues into his realist portrayals whenever possible. The long, bare legs of the woman in ‘Hotel Room’ are a fusion of cream, ash, robin’s-egg blue, lime green and vermilion. The enigmatic power of his work is born in the contrast between his still subject matter and the sheer physicality and vibrancy of his modeling.

The exterior world provided Hopper with a further source of all-American poignancy. The roadside landscape was dotted with crumbling Second Empire houses whose opulence and eclecticism Hopper saw as essentially American. Built before and after the Civil War, many had fallen into disrepair, and by the Depression had been divided into tenement housing or flophouses.

The lone Victorian house became an architectural analogue to Hopper’s isolated hotel dwellers. ‘Rooms for Tourists’ (1945), a standout of this exhibition, demonstrates his talent for portraying the mundane with stunning force. A simple two-story tourist house on a street by night is observed with surgical precision and depicted with tender generosity. The white clapboard and green-shuttered building is subtly illuminated by multiple sources of light. Beyond the right margin of the canvas, a streetlamp washes the front in a dull warmth, casting delicate shadows that reveal window crowns and cornices. In the front yard, a hanging business sign glows with fluorescent light, casting cool tones on the hedge and front portico. Windows reveal a glimpse of a golden interior and the front parlor’s lighting spills out onto the flower boxes. Cobalt shadows enclose the house, magnifying the night’s stillness.

As he was known to do, Hopper worked painstakingly to get ‘Rooms for Tourists’ right. He parked outside the house for several nights, sketching the architectural details from the confines of his car and unnerving the tenants. Isolation, Hopper’s privilege and curse, is with him as he sits alone in the dark, looking in on a house filled with light and life. Ultimately, his intimacy with isolation results in work that’s more than the sum of its cornices and curtains. ‘Rooms for Tourists’ captures a silent sociability, a Hopper-style hygge missing from scenes of more candid discontent such as ‘Room in New York’ (1932), ‘Hotel by a Railroad’ (1952) and ‘Excursion into Philosophy’ (1959).

The Depression, World War Two, the Cold War: Hopper seemed immune to the global events that fed the minds of other artists. What accounted for his enduring focus on hotelscapes? For Hopper, it wasn’t about the highs and lows of life or history, but about what curator Leo Mazow calls ‘the time waiting, the static and in-between moments’. Hopper crystallized life’s unnoticed ephemera, endowing passing moments with ‘a constellation of meanings all their own’.

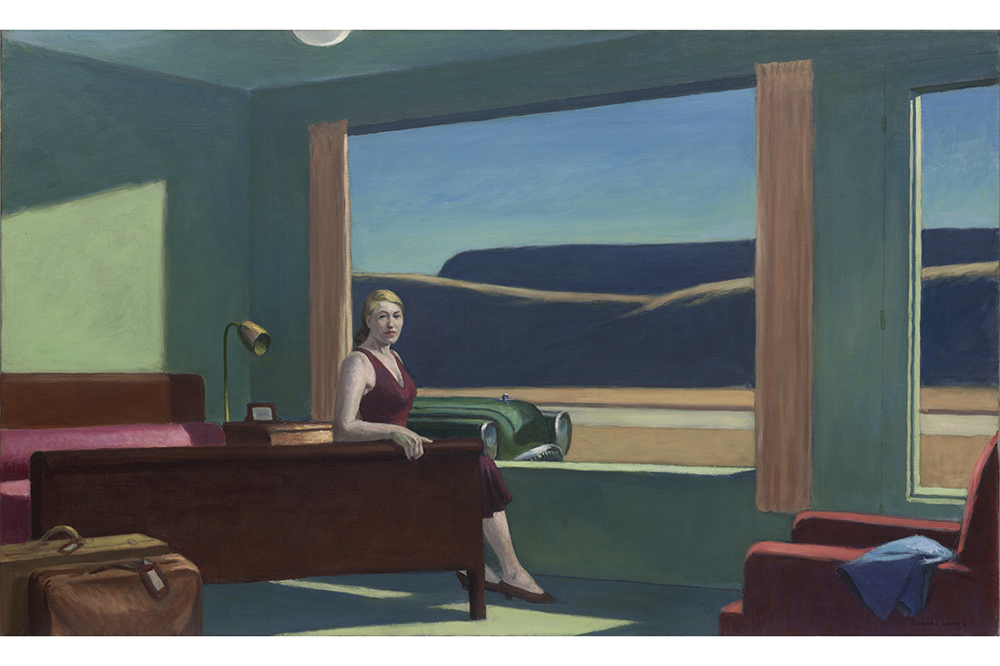

It’s only fitting that an exhibition on hotels offers up a room of one’s own. ‘Western Motel’ (1957), one of Hopper’s later roadside motel scenes, has been recreated as an actual room within the museum for visitors to explore and even rent for the night. In the painting, a woman in a plum-colored dress perches on the edge of the bed in an unlit room. A large window shows a barren landscape at dusk as a green car noses into view. Hopper’s paintings, the Virginia MFA notes, inspired the feel of Hitchcock’s Psycho. Does this Hopper motel, with its invitation to social selfies and bragging, leach the transience from the core of Hopper’s vision?

We don’t know what Hopper the adman turned artist would say. But we can get an idea from a letter he sent to his friend and mentor Guy Pène du Bois after the German conquest of Paris in 1940: ‘It seems that I have no definite philosophy that would be a consolation in these times, but if I had one, it would be of no use to you, for you would not like it and no doubt would despise it.’ Lucky for us he was such a loner.

This article is in The Spectator’s November 2019 US edition. Subscribe here.