There are a lot of theories as to why we are living through a true crime boom. Is it white women fetishizing our pain and fear of men? Is it a psy-op to discredit leftist attempts to defund the police and abolish prisons? Or is it the collective psyche trying to metabolize a few decades of turmoil and violence now that murder rates are down from their Seventies and Eighties peak?

I think it’s less complicated. It’s entertaining, it’s cathartic and it’s a way of externalizing anxiety. You listen to stories of bloody murder and grave injustice, and then you listen to the problem getting resolved as the murderer is revealed, the innocent person released, the mystery solved. Unless of course you got hooked on those cold-case podcasts like I did when they were all the rage about five years ago. Some amateur dived into an unsolved mystery in the hope of uncovering somthing new, but they never did! They always ended with a simple ‘Well, I guess we’ll never know,’ and those are a lot of hours of my life that I will never get back.

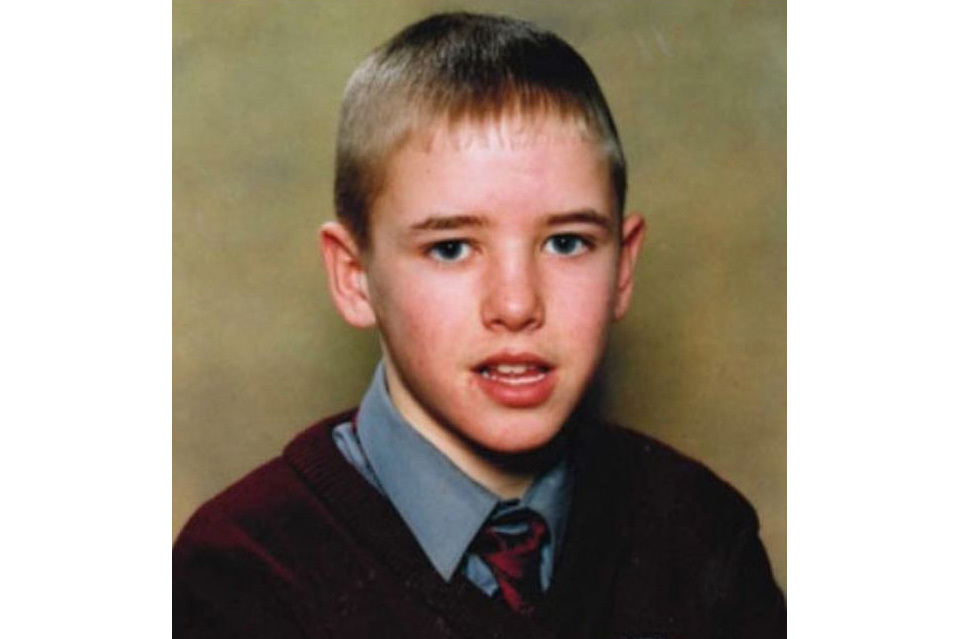

Podcasting rose on the true crime boom — and it’s still the easiest way to build a show and an audience. So it can be difficult as a listener to find something that isn’t exploitative, meandering, or two drunk women speculating on the final moments of a victim’s life. It’s barely gotten started yet, with only a few episodes released so far, but The Witness: In His Own Words is an antidote to all of that. Joseph O’Callaghan tells the story of how he became the youngest person to enter Ireland’s witness protection program. In 2005, aged 18, he testified in the murder trial of two heroin traffickers.

The story isn’t so much about the murder itself as it is about living a precarious life in 1990s Ireland. Surrounded by poverty, drugs and abuse, watching his mother get beaten by first his father and then another lover, being forced to navigate bullies and various predators in Ballymun public housing, O’Callaghan tells not just the salacious crime story but a larger one of social decay and being left vulnerable by the state.

It’s a story that might require Americans to do some googling to fill in the gaps, as words like ‘Ballymun’ and the context of the Irish heroin crisis of the Eighties and Nineties might be mysterious to a foreign audience, but it’s worth doing a little work to bring yourself up to speed. O’Callaghan is a rough but compelling guide through a violent world built by drugs and despair.

There’s another reason we like true crime so much. Tales of murder, rape, drugs and woe have a way of reinforcing whatever theories you’ve come up with to explain the world. Think the world is terrifying? Filling your head with true crime will justify your paranoia. Think the police are racist and ineffectual? Every story of a botched investigation and cases going unsolved will bolster your convictions. Changing someone’s mind about something requires a bit more than just telling them they’re wrong and cracking a few jokes at their expense.

That’s why I admire the second season of Columbia University’s Libraries Shoe Leather podcast, which is told by journalists and historians who have researched their subjects studiously and thoroughly. While the first season took a roving view of New York City’s history, the second season focuses tightly on the unstable 1970s. It was either an era of cultural and radical rebirth or a lawless hellscape, depending on who you talk to. Shoe Leather suggests, eh, it was kind-of a mix of both.

The team at Shoe Leather tell complicated stories with meticulous documentation and careful reconstructions, making stories like the burning of the Bronx or the budget crisis under Ed Koch, stories that have been told again and again, feel fresh and new and devoid of any strong ideological angle. The best episode so far tells the story of Robert Davis, another teenager caught up in forces outside of his control and left unprotected by a failing city’s institutions. He gained media attention as a 13-year- old when he was sent to Rikers, the youngest child ever locked up there. But once the media turned its sensationalizing attention elsewhere, Davis’s life continued. Meg Britton-Mehlisch and Allie Pitchon do a great job filling in what was left out of his story when the papers were using it to wring their hands about a world gone mad.

The Witness and Shoe Leather excel at recovering the humanity of people who were turned into spectacles by the media, politicians and other bad actors. These podcasts might not sell as many security systems to the terrified masses as a story of an unknown killer who’s still out there, somewhere. And they’re all the better for it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.