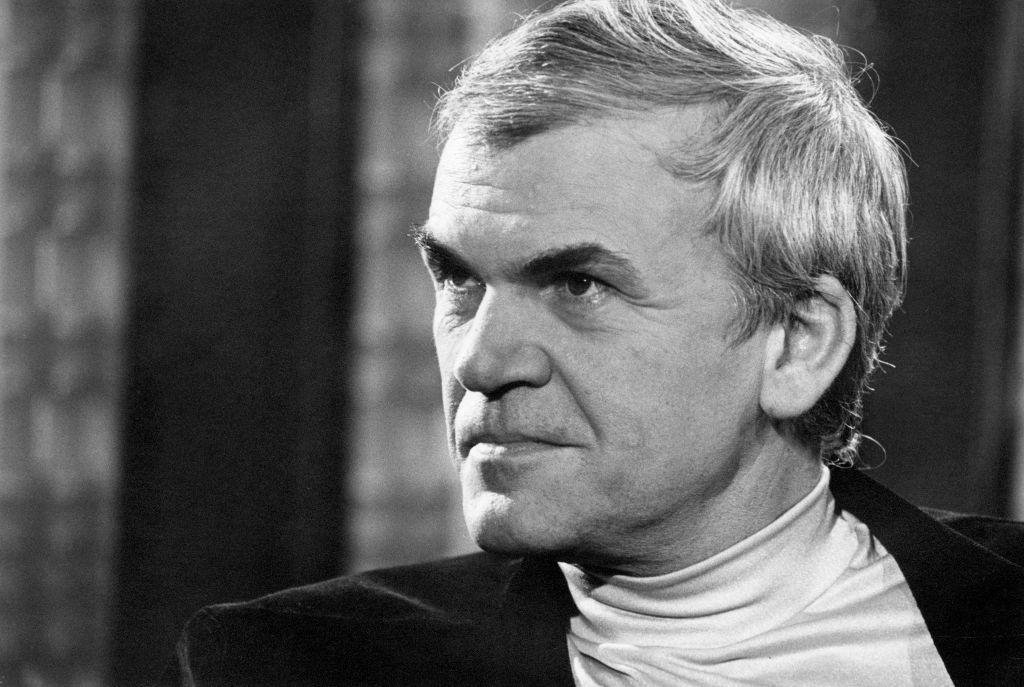

I was just leaving France when I got the news that that the Czech novelist Milan Kundera had died, aged ninety-four. He had emigrated to Paris in 1975, when he was forty-six, a refugee from the crackdown in Prague following the Russian obliteration of the Prague Spring in 1968. He died in his adopted city on July 11, full of honors but also, or so it seems to me, largely forgotten.

I had not been following Kundera’s work for many years. But there was a moment, in the 1980s, when he was the talk of the posh, intellectual literary town. I wrote a longish essay about him for the New Criterion in 1986. I draw on that work here.

Kundera was in his late thirties when he published his first novel, The Joke, in Prague in 1967. The book traces the fortunes and amours of a young student, Ludvik, after his exasperatingly patriotic girlfriend decides to show the authorities a postcard he had written her as a joke: “Optimism is the opium of the people! A healthy atmosphere stinks of stupidity! Long live Trotsky! Ludvik.” As a result of this whimsy, Ludvik finds himself expelled from the Communist Party and the university, and is eventually conscripted to work in the mines for several years.

The appearance of Kundera’s acerbically political novel coincided with — indeed, it was only possible in — the short-lived liberalization of Czech society that has come to be known as the Prague Spring. The Joke went through three large printings in quick succession and instantly won Kundera a wide and enthusiastic readership in his homeland.

It also won him the somewhat less enthusiastic attention of the Communist Party. At the end of August, 1968, Russian troops abruptly occupied Czechoslovakia, putting an end to the Prague Spring and the reformist government of Alexander Dubcek.

In a bitterly ironic variation on the fate of his character Ludvik, Kundera was relieved of his teaching position at the Prague Film School and deprived of the right to work. The Joke was banned and removed from public libraries — “erased,” as Kundera put it, “from the history of Czech literature.”

It was not until the publication of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting in 1980 that Kundera really established himself among the American literary intelligentsia — though, in fact, it did not so much establish Kundera’s reputation here as enshrine it; it elevated him to that pantheon of writers whose productions exist more as untouchable objects of admiration than as works susceptible to critical commentary.

Now, Kundera was indisputably a writer of enormous talent. But precisely because Kundera assumed such eminence, I thought his work deserved more than indiscriminate celebration. Though he developed a voice that was unmistakably his own, his best work exercises an appeal that can be said to epitomize the ethos of modern “dissident” fiction: fiercely intellectual, it is charged with a cool, at times almost brutal eroticism and ironic humor, and it is everywhere at pains to declare its fictionality, to call attention to its novelistic status.

Despite its obvious literary sophistication, Kundera’s work was also deeply political, drawing heavily on his experience of totalitarianism in an effort to explore the difficult spiritual landscape that his characters populate. Kundera by no means always affirmed his status as a dissident writer; on the contrary, from the mid-1980s he strove to qualify, even deny, that status at every turn. But it is, I believe, in the political dimension of his work — or, more accurately, in the ambiguous attitude Kundera adopted toward the political dimension of his work — that we will find an important source of his tremendous appeal both in this country and in Western Europe.

Kundera underscored his allegiance to the fundamental Enlightenment values of skeptical rationality and individualism — traditional liberal values that he summarized in another essay as “respect for the individual, for his original thought, and for his inviolable private life.” It is no secret that these values have come increasingly under siege in modern society, most brutally and systematically in totalitarian regimes, but also, Kundera would insist, in democratic regimes, where the imperatives of mass culture compromise private life and discount genuine individuality.

It is of course this latter insistence — that freedom and man’s privacy are threatened as much in Western democracies as under communism — that won Kundera so many friends on the left, for whom the defiant, anti-communist stance of the dissident writer is perfectly acceptable provided that his defiance extends to all expressions of authority, notably to those that provide a haven for his dissidence. But taken in conjunction with his attempt to downplay the frankly political message of his work, Kundera’s criticisms of the West highlight ambiguities at the heart of his position — ambiguities that force us to question the good faith and ideological motives of this troubling writer.

Time and again, Kundera praised the “wisdom of the novel” as a counter to the leveling influence of modern society. In the midst of an environment hostile to private life and the integrity of the individual, the novel appears as a sanctuary where the “precious essence of European individualism is held safe as in a treasure chest.” It is thus not surprising that the major thematic concern of Kundera’s fiction, from The Joke through The Unbearable Lightness of Being, was with the fate of the individual in modern society, especially in modern Communist society.

In many ways, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting was Kundera’s most accomplished work. With it he perfected his digressive narrative technique, in which themes are stated, developed, transformed and interwoven more or less on the model of a musical variation — an analogy that Kundera had been fond of invoking when describing his writing.

Yet in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Kundera’s “variations” — his excursions into philosophy, say, or intellectual history — never strike one as being mere intellectual decorations, inessential to its life as a novel, as they do, at times, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being. The book follows the melancholy, often overlapping careers and erotic entanglements of several sets of characters as they struggle to salvage some sense of joy and vitality, some sense of themselves as individuals, against the bleak backdrop of communist Czechoslovakia.

Given the self-consciously playful character of Kundera’s novels, it is hardly surprising that he cited Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and Diderot’s Jacques le fataliste as crucial inspirations. And while the tone and “feel” of Kundera’s fiction is distinctly more modulated — more “linear,” you might say — than those rambunctious early novels, their influence can be felt throughout his work, both in its self-consciously digressive narratives and in the ironic humor that Kundera insinuates into even his most stringent philosophical meditations.

Kundera also specialized in that brand of emotionally distanced, often farcical, eroticism that has become a hallmark of so much modernist and “postmodernist” fiction. Here again, we can see the influence of the ribald tradition of Sterne and Diderot. Diderot’s novel especially is celebrated by Kundera for its “explosion of impertinent freedom without self-censorship, of eroticism without sentimental alibis.”

In fact, though, Kundera’s depictions of sex were edged with a loneliness and even desperation quite absent from the more playful work of his acknowledged precursors. His fiction abounded in explorations of what we might call intimacy in distress. The erotic lives of his characters became a theater in which a wounded individuality, half capitulating to forces inimical to it, struggles to preserve itself. As Kundera put it in the interview with Philip Roth that appears as the afterword to The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, “with me everything ends in great erotic scenes. I have the feeling that a scene of physical love generates an extremely sharp light which suddenly reveals the essence of characters and sums up their life situation.”

The cumulative — and carefully calculated — effect of Kundera’s style was fiction endowed with a sense of great immediacy and directness, with a nimbus, so to speak, of reality. Though we are everywhere reminded that we are reading fiction, in the end such reminders tend to increase rather than diminish our confidence in the authority and truthfulness of the narrator. “It would be senseless for the author to try to convince the reader that his characters once actually lived,” Kundera wrote of his main characters in The Unbearable Lightness of Being. “They were not born of a mother’s womb; they were born of a stimulating phrase or two or from a basic situation. Tomas was born of the saying ‘Einmal ist keinmal’ [‘Once is never’]. Tereza was born of the rumbling of a stomach.” It is all merely fiction, yes, but we somehow feel that in admitting this the author is taking us into a deeper confidence, preparing us for some important truth.

Probably the central critical element in Kundera’s work was his attack on sentimentality. This took various forms, and was evident throughout his writing, in his essays as well as his novels. Everywhere there is a deep suspicion of sentimentality, of feeling un-scrutinized by doubt. Thus he poked fun at “the obscure depths,” the “noisy and empty sentimentality of the ‘slavic Soul.’” And in his introduction to Jacques and His Master, he criticized Dostoevsky’s novels for creating a “climate… where feelings are promoted to the rank of value and of truth.”

For Kundera, the battle against sentimentality was at the same time a battle against forgetting. “The struggle of man against power,” we read at the beginning of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, “is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” In Kundera’s terms, the struggle of memory against forgetting is man’s struggle against whatever social or psychological forces would deny the continuity and individuality of his personal history. Hence the attack on sentimentality was only the other side of his defense of individualism. For it is just this — the lonely and irreducible privateness of experience — that sentimentality promises to dissolve. The essential appeal of the sentimental is precisely that it relieves one of the burden of individuality and the responsibilities of adult experience.

Kundera, as a novelist, maintained that he is not in the business of taking positions. “Now, not only is the novelist nobody’s spokesman,” as he put it in one essay, “but I would go so far as to say he is not even the spokesman for his own ideas.” He goes so far, in fact, as to insist that we view his work as little more than an ironic game, as writing “on the level of hypothesis.” This was evident, for example, in his objection to being regarded as a political writer. Admitting that he detests communist regimes, he hastens to add that “I detest them as a citizen: as a writer I don’t say what I say in order to denounce a regime.” A political reading of his work, he suggested in one interview, is “a bad reading.” Even the label “dissident writer” annoyed him because it imports a political terminology that he claims to be “allergic” to. Again, in the 1982 preface that he contributed to The Joke, Kundera recalled that “When in 1980, during a television panel discussion devoted to my works, someone called The Joke ‘a major indictment of Stalinism,’ I was quick to interject, ‘Spare me your Stalinism, please. The Joke is a love story’” — this in a book whose entire psychology is unintelligible without the assumption of such an indictment.

Of course, there is an important sense in which Kundera was right: fiction does exist “on the level of hypothesis,” not on the level of fact; novels are not position papers. But there is something deeply disingenuous about appeals to the hypothetical or gamelike character of fiction when those appeals are meant to mask or deny the very real political content of one’s work. And this, unfortunately, was the effect of Kundera’s rhetoric. For like so many dissident writers, Kundera, though he embraces Western culture and Western freedom, maintained a fundamentally equivocal attitude toward the West. True, as he would have been the first to point out, there is much to bemoan about the aggressive superficiality of Western mass culture and the tasteless intrusions of the media into our private lives. But it is one thing to criticize these cultural failings, quite another to pretend that they are in any relevant sense cognate with the evil of totalitarianism — to pretend, that is, that they are somehow merely different versions of the same spiritual malaise.

In fact, though, in statement after statement this is precisely the posture that Kundera adopted. In an interview with Philip Roth that appeared in the Village Voice, for example, Kundera was asked if he thought private or intimate life were less threatened in the West than under communism. “The evolution of the modern world is hostile to intimate life everywhere,” he replied.

The implication is clearly that one’s privacy and intimate life are just as much in jeopardy in a Western democracy as they are under communism — perhaps more insidiously in jeopardy in a democracy, for in a communist society one at least knows where one stands and there is no attempt to glorify shallow curiosity in the name of freedom of the press. The habits of the media in the West often border on obscenity; but to suggest that it is somehow comparable with the brutality of totalitarianism is absurd.

In effect, Kundera wanted to have it both ways: he wanted both the freedom of fiction and the authority of historical fact; he wanted, that is, cachet of being a dissident writer without the uncomfortably definite political commitments that that status brings with it. Instead, he strives to maintain a completely ironical view of the world, a view that would exempt him from any definite commitment — a view that Friedrich Schlegel, the great theorist of Romantic irony, aptly dubbed “transcendental buffoonery.” Thus Kundera describes the “basic event” of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting as “the story of totalitarianism, which deprives people of memory and thus retools them into a nation of children,” and yet still insists that “no novel worthy of the name takes the world seriously.” But how can a novel recount “the story of totalitarianism” and not take the world seriously? No one would suggest that Kundera’s writing should be reduced to its political content; but to dismiss that content as part of a “game,” as incidental embellishment or atmosphere to what is really a “love story,” “merely a novel,” is to ignore the element that, more than any other, grants it its authority and weight.

By insisting on the purely novelistic status of his work, Kundera brewed an intoxicating potion of his own. Indeed, it was all the more powerful for the whiff, the suggestion of truth and reality that it purveyed. And it was there, perhaps, that we witnessed most clearly the essential ambiguities of Milan Kundera — ambiguities that were not, alas, the inexhaustible ambiguities of human nature but the meaner, more predictable ambiguities of a writer struggling to maintain a predefined image of himself as ideologically correct. RIP.