Halfway through the first part of HBO’s extraordinary documentary Leaving Neverland, I flicked through the comments on social media in order to gauge the global reaction. Surely, I thought, Michael Jackson’s reputation will never recover from these bombshell revelations.

If you sat, squirming, though Dan Reed’s excruciatingly prurient documentary you’ll know what I mean. Lots of those who didn’t have been justifying their decision to ignore it with excuses like ‘Yeah, but we knew this already. Michael Jackson was a pedo. It’s hardly news, is it?’ But this strikes me as glib and dishonest.

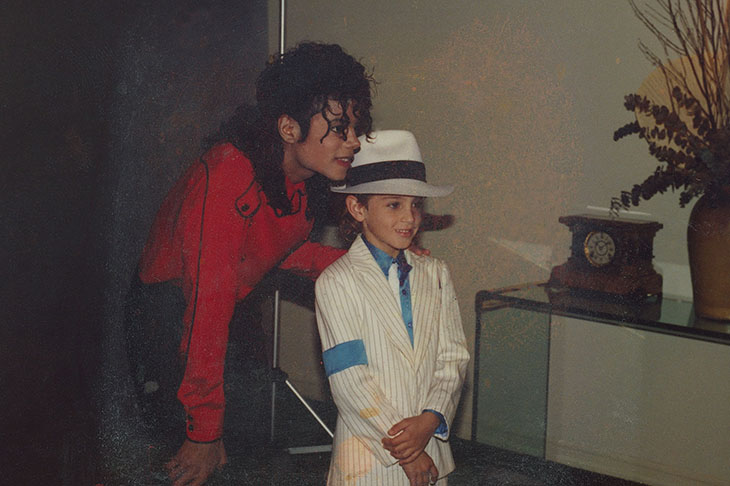

Sure, Wacko’s fondness for prepubescent boys — such as Jimmy Safechuck, the 10-year-old Australian lad who joined in his dance routines on the late 1980s Bad tour — was the subject of much ribald speculation. Comics, especially, had a field day seeing how close to the edge they’d dare go. Jimmy Carr: ‘I’m not saying Michael Jackson is guilty. But if I was a billionaire pedophile, I’d buy a funfair for my back garden.’ But most of us, I think, still preferred to tell ourselves that Wacko was simply a very strange man who’d been kept in a state of arrested development by his grim father and his demanding tour schedules; that, as a consequence, he was just a sexless Peter Pan figure who simply preferred the company of boys his own mental age.

If this seems naive with hindsight, it didn’t at the time. ‘Why did the parents let their kids sleep with him?’ everyone’s asking now. But this painstaking, sensitive, utterly damning documentary makes the answer perfectly clear: because Jackson’s genius for pop was surpassed only by his genius for hiding his pederastic tendencies. His entire career and persona, you might argue, were just one gigantic honeytrap, erected with the purpose of luring pretty little boys into his web of sin.

Jackson’s celebrity (and elusiveness) made boys and parents alike pathetically grateful for his attention — and the private-jet flights and hotel suites. His music made them love and idolize him. His money — as Carr jested above, but it’s true — bought him a huge remote estate with a funfair and endless bedrooms and doors and secluded attics perfect for seducing children in, unbeknown even to his staff.

He was so cunning a deceiver that even now — this is what so shocked me when I looked on Twitter — the majority of fans still seem angrily determined to take his side. The two boys featured in the documentary — Safechuck and Wade Robson (who was just seven when the abuse began) — are liars, they say, motivated only by money. So how, in the absence of any hard corroborating evidence, do we know which version of events to believe?

What clinched it for me was the matter-of-factness of the boys’ and families’ testimonies. Reed sat them all down in front of the camera and let them tell their story, as it unfolded. Safechuck, we learned, was introduced by Jackson to masturbation while in a hotel suite in Paris on the Bad tour. There were many more cringe-inducing details than that, which I’ll spare you. Suffice to say that by the end the picture was just too horribly plausible and coherent to be dismissed as a confection.

And very sad too. In the closing credits, Wade Robson is shown on a beach burning the memorabilia, including the trademark glove, that Jackson gave him as lover’s gifts. At the time, those boys really did feel as though they were enjoying a passionate romantic relationship with their idol, and were mortified when Jackson cast them aside for younger models. It’s probably another reason why it took so long for the truth to come out: subconsciously they still wanted to protect their abuser.

Ricky Gervais’s new sitcom After Life (Netflix) is a lovely, tender, low-key, moving meditation on love and loss. Plus some amiable jokes. Is this what we were hoping for from one of the few globally enormous comics prepared to take on ‘woke’ culture and fight for the right to go on making jokes about the most tasteless subjects imaginable?

Speaking for myself, no. I have no problem with the fact that Gervais recognizes his limitations and makes the main character in every sitcom he writes a thinly disguised version of himself. What does bother me, slightly, is the wasted opportunity. It’s interesting that the running joke in After Life is essentially the same as the one in that BBC Three comedy I reviewed the other week, Jerk, which is yet to be picked up by a US network. In Jerk the main character acquires the ‘superpower’ of being able to say whatever he likes without consequence by dint of his disability (cerebral palsy). In After Life, Gervais gains the same ‘superpower’ by dint of having been recently widowed.

Why the coincidence? Well, obviously because there is a massive, unsatisfied yearning in our culture for freedom of speech. Gervais could have gone in hard with this, but instead he has chosen to pretend that his comedy is about something else, somewhat blunting his satirical edge. Pity.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine. Subscribe to James Delingpole’s streaming and TV email Vidi here.