Reihan Salam has written a timely and important book, urging centrists of left and right to accept reduced immigration in order to improve social cohesion and integrate the children of immigrants. As a prominent Bangladeshi-Muslim American conservative, he brings a highly distinctive perspective to this vexed question – a second-generation immigrant’s case for immigration reform.

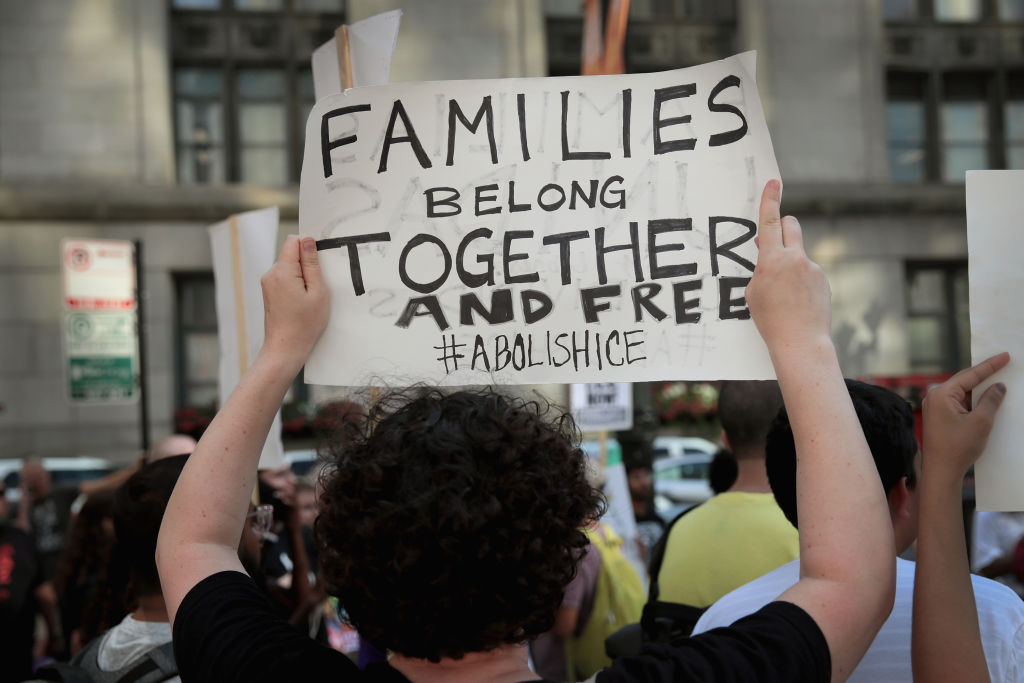

Immigration was the defining issue of Donald Trump’s primary bid, and analyses of survey data show that non-voters and Obama voters who wanted lower immigration were decisive for Trump’s election. Yet the rise of the post-1960s New Left, with its focus on disadvantaged cultural groups, has made inroads into the Democratic Party, rendering it allergic to immigration control. As with other issues that touch on race, immigration has emerged as what Scott Atran terms a sacred value, an indisputable good which the Democratic party cannot pledge to reduce – unlike the more pragmatic approach of the Clinton and early Obama eras. While the party can be flexible about longstanding conservative issues such as guns, religion or the scope of the welfare state, immigration is a progressive religious totem that is not up for discussion. Trump’s politicisation of immigration presses on progressives’ deepest sensitivities, eliciting irrational responses like calls to abolish ICE or the category of illegal immigrant. Meanwhile, Trump’s attacks on immigrant groups poured fuel on the flames. In this climate, it becomes impossible, writes the author, to have a rational debate and calmly reach an accommodation between competing camps.

As Salam points out, many Democrats seem to have adopted a quasi-open borders position which eschews border control and considers deportation a sin. Yet the number of people in the world who would move to America if they could numbers in the hundreds of millions. Moreover, higher inflows are incompatible with the egalitarianism many progressives cherish because low-skilled immigration hits poor immigrants hardest and exacerbates inequality. Those ‘who want more open immigration policies and a more equal society,’ writes Salam, ‘want to have their cake and eat it’ and are ‘crushingly naïve’.

The book breaks new ground by opening readers’ eyes to the plight of many urban immigrants and their children, who struggle to make ends meet and bear the brunt of competition with new immigrants at the bottom end of the labour market. There is a bifurcation among immigrants between the high-skilled Elon Musks and Satya Nadellas, who are on an assimilation path, and the low-skilled, who risk becoming a trapped and racialised underclass. For instance, two Hispanic Americas are forming: while a majority of third generation Americans with Mexican ancestors are of mixed ancestry (usually Hispanic-White), native-born Hispanic women with a degree are three times more likely than native-born Hispanic women with less than high school to be have married outside their group.

While newcomers may be better off than they were in Latin America, Africa or Asia, their children start life with higher expectations of American society, which it is ill-equipped to fulfil. By contrast, during the country’s postwar boom, many could rise up the economic ladder. America’s immigration pause of 1924-65 also made a difference, easing competition at the bottom end of the labour market, allowing Catholic and Jewish immigrants to better themselves while narrowing the cultural distance between diverse cities and the Protestant mainstream. This social healing seems a dim prospect today.

What America desperately needs to do, Salam argues, is assimilate the newcomers into a common nationality, paving the way for their economic ascent. To continue to accept large numbers of low-skilled immigrants in an economy with few well-paid manual jobs is a recipe for rising social tension and polarisation. The risk is that Hispanic, Caribbean and to some extent Asian, migrant families will become stuck in a cycle of poverty, segregated both economically and culturally from Middle America. Indeed, 46 per cent of immigrant-headed families rely on food assistance compared to 31 per cent of US-born households. While terrorism is a possible response among the frustrated second-generation, a more prosaic outcome is a fraying of the bonds of national unity as diverse, ethnically-stratified cities drift away from the white-majority heartland. Thus while Salam is as critical of Trump’s rhetoric as his pro-immigrant family members and liberal friends, he is ‘closer to him’ on immigration than they are.

Salam seeks a shift away from family reunification – which accounts for two-thirds of America’s influx – toward a greater emphasis on skills in order to reduce pressure on low-income Americans. He urges the government to invest in training to meet the challenges of the future, which will include the large-scale replacement of many jobs by robots. The goal should be to permit the lowest-paid jobs to flow offshore while improving the productivity of American labour through higher-paid employment in activities demanding higher skills.

Salam’s work is influenced by centrist, liberal-nationalist writers like Michael Lind and David Goodhart, who espouse strong welfare protections alongside an assimilationist cultural nationalism. This recalls the outlook of the Populists and Progressives at the turn of the twentieth century as represented by figures like Teddy Roosevelt. Their combination of centre-left economics and cultural conservatism has been missing in western politics for nearly a century because it cuts against the cosmopolitan predilections of the intellectual elite. On the right, libertarianism has been influential while on the left, anti-nationalist liberalism reigns supreme. Trump represents a break with these elite traditions, though he has given ground to the libertarian Republican establishment on infrastructure, social programmes and tax policy. Salam also criticises Trump’s cantankerous relations with other countries, notably Mexico. America, he argues, should help improve conditions in Mexico and work bilaterally with it to regulate Central American migration.

It’s difficult to quibble with much in the book but there is an important tension in the argument which remains unresolved. On the one hand, it approves of the beneficial effects of the 1924-65 pause, yet Salam steps back from endorsing reduced legal immigration. Though opposed to open borders, this puts him fairly close to where Obama was in 2014: willing to enforce the border, but loath to challenge the taboo against reducing legal immigration. In calling for ‘rebalancing’ toward higher-skill immigration rather than reduction; and for amnesty with a promise of tighter future control, he remains within the ambit of Democrats’ Overton Window of the acceptable. Yet, as Salam adroitly recounts, many on the Republican side have lost trust in the immigration system due to years of lax enforcement and rising numbers. Survey data suggest they seek a slower rate of change. As in Europe, any rapprochement on this issue will probably require lower numbers, at least for a time, if only as a gesture to conservatives that legal immigration is not an article of faith but a policy knob which may be adjusted up or down through democratic negotiation in an atmosphere free from accusations of racism.

All told, Melting Pot or Civil War is a superbly-written book which makes a genuinely original contribution to an important debate.

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck, University of London, and author of Whiteshift: Immigration, Populism and the Future of White Majorities.