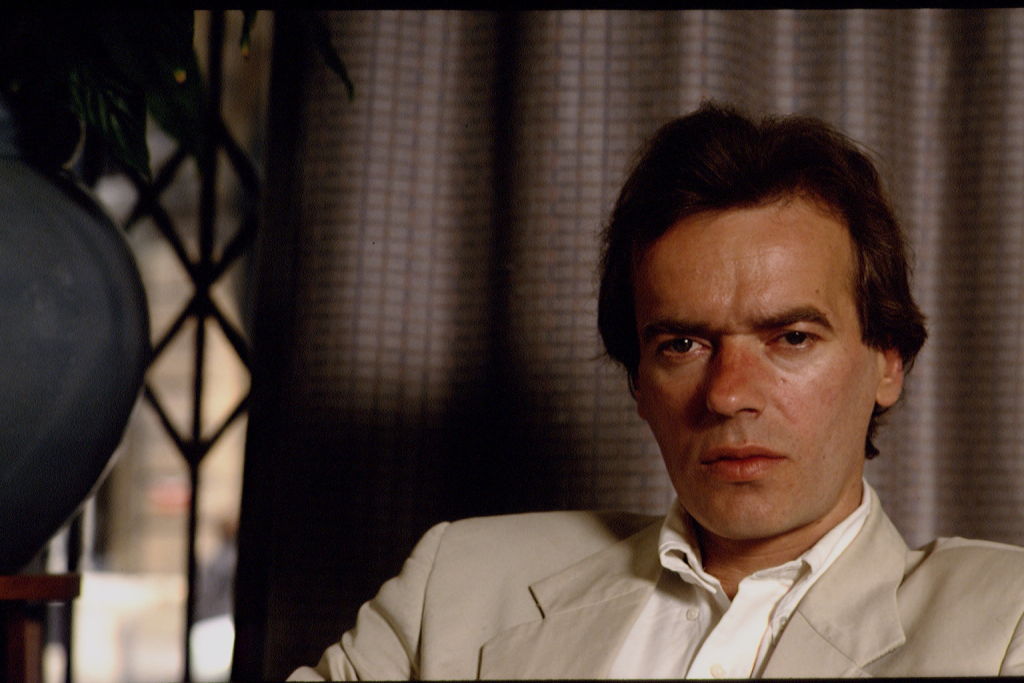

Martin Amis had impeccable timing, as anyone who looks at his sentences, paragraphs, chapters, books ought to admit. He died fifty years exactly after the publication of his first novel, The Rachel Papers, and the beginning of this wayward, unflinching, confrontational genius’s hold on us, and on fiction expressed in English prose.

Not many novelists, even the very greatest, have a career that lasts fifty years. Dickens’s lasted a little over thirty; Henry James the same; Waugh not much more than that, and sometimes it’s very much shorter. Jane Austen’s was over in six years. A novelist who continues to claim our attention as long as Amis can reasonably expect to fall out of fashion, and this certainly happened to him. His last major novel, The Pregnant Widow, a beautiful, evocative, tender piece of work, was greeted with contemptuous reviews on its publication in 2010. The total lack of respect and critical consideration that had long emerged from some professional quarters seemed to have, at last, had the impact on his readership and popular opinion that his detractors had hoped for.

As I write, I have on my desk a proof copy of what pretends to be a history of the novel in English since 1970, by a reviewer for a Sunday newspaper. It finds space for the novels of Harry Sidebottom, Sarah Moss, Barry Unsworth, Edwina Currie, David Cook, C.J. Sansom and many other unobjectionable triflers. It doesn’t, however, think it worth mentioning Martin Amis’s Money, the book that transfixed a generation of writers and readers, and one which, sentence by sentence, remains one of the most electrifying novels in English since Lolita. Amis’s reputation is at a low point, as Trollope’s, Wilkie Collins’s or Amis’s father Kingsley’s were at their death. I don’t think there’s much serious doubt that these superb books will return.

Money is a masterpiece

He said much later that vulgar curiosity would have persuaded any London editor to have accepted his first novel, The Rachel Papers. His father, Kingsley, was at the height of his celebrity and also, in the early 1970s, of his literary mastery. Kingsley’s late Sixties novels I Want It Now and Girl, 20 are revelatory accounts of what a seriously dedicated chronicler of English usage can do with contemporary social realities. His stepmother, Elizabeth Jane Howard, was also at the peak of her literary authority. Of course they published him; but they went on publishing him.

Those first four novels, The Rachel Papers, Dead Babies, Success and Other People are invigorating, slack-jawed disruptions of novelistic conventions. The first is that ludicrously exhausted topic for the comic novel, the attempted seduction of a girl. It is wonderfully knowing, however, about its superficial banality; one of its funniest scenes has the hero and his girl loitering outside a pharmacy; they go in; they ask for contraceptives; the chemist hands them over and takes the money, and they leave. You have to know what a cliché of the postwar comic novel the condom-buying scene was to get the joke. Dead Babies is an undeniably disgusting comedy of excess, set within a series of social hierarchies — money, class, looks, physical desirability — which it gleefully destroys. Interestingly, it has pretty well exactly the same plot and setting as his father’s contemporaneous Ending Up. Other People is a “mystery story” which remains a mystery, like one of those Renaissance paintings intended as a ‘puzzle picture’ to test the audience’s wit; it begins by making the whole world unfamiliar, and ends with the single solution tantalizingly held just out of the reader’s grasp.

It’s the third of this group, however, Success that pointed towards Amis’s future path. It is the first of his novels to have a structure as clear and artificial as a geometric diagram. The narrators, two step-brothers, alternate. The components of social class are parceled out; one brother has mastered the artificial codes of behavior and speech; the other can’t gain access, but is steadily mastering money. Two ways of talking alternate; the first, an agonizingly affected patrician style — “The spacious drawing room… was, in days of yore, an ample stage upon which the blessed young Ridings could muse and wander, wander and muse…” The second, a more ordinary witness, observing the confident life of the streets and backrooms — “I mean, you don’t have to be… Maynard Keynes to work that out.” The discourses alternate; crack; dissolve. It is intensely stylized — the last line of the book is a perfect iambic hexameter — and full of energy, half-unleashed.

In his lifetime, the gossip-column facts blocked out just how good his novels are

By this point, Amis was highly successful in worldly terms — his father complained that he had gone abroad in 1978 for tax reasons. The acclaim of the establishment was more elusive. Like his hero Nabokov, Amis never won a literary prize. His work was at once alluringly appealing, and at odds with conventional contemporary literary values. It was funny; it often had no obvious subject-matter; it made judgements; it used conventionally offensive words for facts of race, sex, sexuality without endorsement, but without pious denunciation either.

His next novel, Money, is a masterpiece. It manages with only the slightest plot, relying on Amis’s astonishing resourcefulness to create incidents, and a mad, irresistible voice. By now, Amis’s prose mannerisms were much imitated, but this narrator’s voice is irresistible, and fresh; it moves seamlessly from articulate London street to an entranced evocation of place where every fifth word is surprising, and absolutely right; “In the gogo bar men and women are eternally ranged against each other, kept apart by a wall of drink, a moat of poison, along which mad matrons and bad bouncers stroll.” There is much the same mastery in London Fields, the most ruthless of his geometric structures; a four-pointed narrative where three of the points (a thug, a posh boy, a woman with universal sexual appeal) are given the utmost cartoonish exaggeration. The Information, a brutal comedy of literary London, failure and undeserved success, followed; its sumptuous and brutal pastiches made one realize how much of Amis’s writing was intensely engaged with writing itself. Even Quentin, in Dead Babies, gets his social cachet from being a book reviewer.

Perhaps this was the point at which the literary culture began to turn decisively away from what Amis’s virtues most conspicuously embodied. He identified his ambition to fight, in the title he gave an essay collection, “the war against cliché”; it might have to be concluded, that was a war he lost. He responded to the mood in starting to write the sort of books that seemed to be given wider value than the non-committal, ludic, unpredictably and inconclusive form of the novel. He wrote two volumes of memoirs, which were alternately described as the best things he ever wrote, and attacked for not being factually correct, that least convincing of literary criteria. Literary culture had started to elevate historical fiction, but Amis’s ventures into it were out of tune with the prevailing principles of well-researched accuracy, avoidance of humor, a horror of anything resembling playfulness.

His best novel in this vein, Time’s Arrow tells the life of a Nazi war criminal through the voice of an incubus, and backwards; in it, Auschwitz is a brilliant, traumatic exercise in restoring millions of Jews to life, and in the years to come, their civil rights are restored, one by one. Horrifying and profoundly, perversely affecting, Time’s Arrow nevertheless broke all the rules of engagement with its subject. Not least because it civilly assumes that the reader will know about the subject; like all Amis’s books, it is meant for an intelligent and worldly reader.

It, and all his work, will remain controversial for a time. Perhaps in his lifetime the gossip-column facts — the teeth, the feuds, the passing comments, the unsuspected children — blocked out just how good these novels are, how witty, how inventive, how incidentally insightful. As time goes on, the fake outrage will disappear, and the virtue-signaling denunciations; the memoirs will sink to a proper place in his work; and we will still have the tennis match in Money, Stanley Veale at home, Steve Cousins displaying his unrivaled knowledge of Richard’s terrible novels in The Information. Or the unforgettable, unforgivable page in London Fields that tabulates Keith Talent’s mistresses. We might, now or in the future, echo that, and say about Amis that, well, it was true that Martin had something to be said for him. Martin had a certain quality. He was best.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.