In a world gripped by Nineties nostalgia, everything old is new again. Bootcut jeans and birkenstocks are back; old Nickelodeon classic cartoons are being rebooted for a new generation. But the strangest renaissance in this throwback moment is a moral panic: Marilyn Manson, the creepy goth-rocker with a startling appearance and a voice like synthesized nails on a chalkboard, is once again up for cancellation.

The difference is in who’s doing the canceling — and that this time, it seems it might actually stick.

Once upon a time, back in the late 1990s, Manson was the guy whose albums you hid in your underwear drawer lest your parents find them and freak out. It wasn’t just the music itself but the man who made it, and what he seemed to represent. Rumors swirled around Manson and the evil influence he and his music held over impressionable youngsters. If you were a teen at the time, you would have heard them all, each more sordid than the last: that he’d had his ribs surgically removed so that he could fellate himself, that his fandom was made up of school-shooters and Satan worshippers, that he opened every concert by flinging a sack of kittens and puppies into the crowd. The music wouldn’t start, people said (here lowering their voices for dramatic effect), until all the puppies were dead.

Of course, absolutely none of this was true. (The thing about the puppies wasn’t even original; long before Marilyn Manson rose to fame, people spread similar rumors about Ozzy Osbourne and Alice Cooper incorporating animal cruelty into their acts.) But the fact that it seemed possible — at least to the nervous grownups who slapped content warnings on Manson’s CDs and fretted that his music would make kids want to kill themselves — was part of the appeal. Listening to Marilyn Manson was about rebellion, an act of proud defiance. His darkness wasn’t just something we tolerated, brushing aside to enjoy the music; the darkness was the point. Written into every line of Manson’s songs was the promise of catharsis. Here was a musician who expressed all the rage, the fear, the nihilistic hopelessness that we felt but couldn’t give voice to, and the fact that our parents found him terrifying only added to the allure. If not for the panic he inspired in various authority figures, he wouldn’t have been half as cool.

And now Manson is back under scrutiny — not for his onstage antics, but for his offline transgressions. The man who conservative parents everywhere believed was Satan’s minion is now just another middle-aged #MeToo case, the most ordinary sort of jackass who (allegedly) treats his girlfriends like garbage. The controversy began on February 1 with an Instagram post by Evan Rachel Wood, who was in a relationship with the musician from 2007 to 2010.

‘He started grooming me when I was a teenager and horrifically abused me for years,’ Wood wrote. ‘I was brainwashed and manipulated into submission. I am done living in fear of retaliation, slander, or blackmail. I am here to expose this dangerous man and call out the many industries that have enabled him, before he ruins any more lives. I stand with the many victims who will no longer be silent.’

Wood has been joined by several other women alleging abuse by Manson, who denies the allegations; his own Instagram post describes them as ‘horrible distortions of reality’. But here’s where the retread diverges from the original: 20 years after religious groups picketed Manson’s concerts and blamed him for the corruption of America’s youth, one millennial woman has accomplished what a million pearl-clutching warnings from the likes of the Parents’ Television Council could not. In the weeks after Wood leveled her accusations, Manson was dropped; first by his label, then his agent. The new Creepshow TV series, for which he had already filmed an appearance, announced that his segment would be scrapped. The denunciations from fans-no-more are still rolling in.

Marilyn Manson has been canceled.

What changed? Not Manson, that’s for sure. He’s just as freaky and misanthropic as he’s always been; the mistake was seemingly ours, in imagining that his public persona was something other than genuine. One writer for the Guardian reflected on the rocker’s intentional courting of controversy over the years, including the time he told an interviewer that he fantasized about beating Wood (by then his ex-girlfriend) with a sledgehammer.

‘What was that?’ the Guardian mused. ‘A red flag or “Manson just being Manson”?’

As the meme goes, why not both? Manson’s entire schtick, indeed the source of his success, is that he has always been like this, a red flag in human form. But we loved him for his brokenness, for the way he lashed out at a world that didn’t understand…until, suddenly, we didn’t.

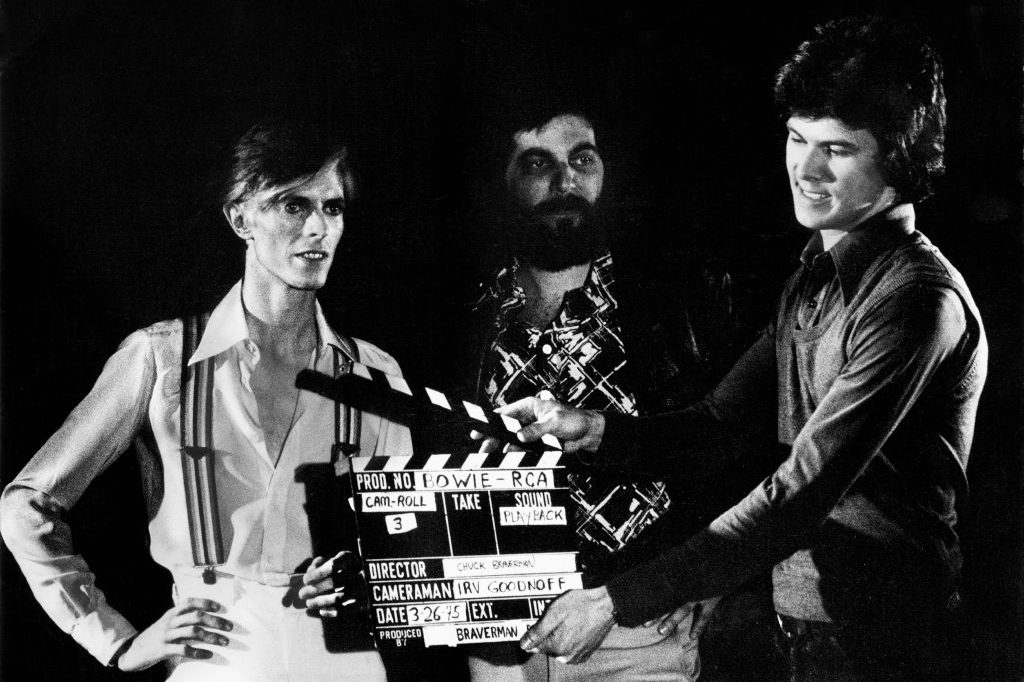

It’s not him. It’s us. Rebellion used to be sexy, and bad used to be so, so good. It was the countercultural cachet of men like Marilyn Manson that made them the objects of desire — in the 1990s, but also long before. Nobody ever looked at Mick Jagger or David Bowie and thought about bringing them home for Thanksgiving, trapping them behind a white picket fence with a golden retriever and a minivan. But audiences grow up, norms evolve, and the trinity of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll isn’t as holy as it used to be. Picture the androgynous rock god, gyrating in leather pants and an overstuffed codpiece, his face smeared with makeup and his sinewy body slick with sweat: is this a creature that can even survive in 2021? There’s no place anymore for a Bowie or a Jagger on today’s spectrum of male desirability, which has Chris Evans in full Captain America beefcake mode at one end and Ben Affleck’s dadbod at the other.

This backdrop for Manson’s downfall speaks to the waning appeal of the swaggering bad boy, accompanied by a sudden wave of paternalistic anxiety about the women who wanted them. What used to be dangerously sexy is now emotionally unsafe. The sons of the sexual revolution have become the creepy old men of the #MeToo era; the teenage groupies of the Seventies are now graying grandmas filled with regret. You could see the shift happening in real time, the stories losing their sparkle as glamorous seduction started looking more like statutory rape. Lori Mattox, who was once famous on the Sunset Strip for her dalliances with rock stars, was still waxing poetic in 2015 about her teenaged affair with an adult David Bowie: ‘I was an innocent girl, but the way it happened was so beautiful. I remember him looking like God and having me over a table. Who wouldn’t want to lose their virginity to David Bowie?’

But fast forward a few years, and Mattox changed her tune in keeping with the times. ‘I wouldn’t want this for anybody’s daughter,’ she told the Guardian. ‘My perspective is changing as I get older and more cynical.’

What somebody’s daughter might want for herself is, of course, not something Mattox cares about; as with so many other things, the boomers are pulling the ladder of sexual libertinism up behind them. We’re rethinking women’s agency in a world where fun and freedom have been replaced by a fixation on power and oppression. And if men always have the upper hand in matters of sex, surely the rockstar has the uppermost of all. It’s the patriarchy, with bass. Think of all those girls, swooning and screaming for Elvis, for Jagger, for John and Paul and George and even Ringo. For the punk rockers and the metalheads; for the boy bands and the emo queens. The beat of the drums was the beat of your heart; the ecstasy was in the music. Even the ones who didn’t hover by the VIP entrance at the end of the night hoping for a brush (or more) with fame felt like they’d been touched. Now we’re asking them to wonder if it was consensual.

And so, the age of the bad boy heartthrob seems to be at an end — and our ability to love the good art of bad men is once again under scrutiny. What are we to do with someone like Marilyn Manson, who never drew clear boundaries of his own between the performance and the person? How can we still listen, when the music is the man and the man is the music? But maybe we won’t want to; maybe this is how culture moves on now. What used to be a titillating dangerous fantasy isn’t anymore; instead, what Manson represents is the most boring sort of bad. A mass-produced, hashtagged product, as banal as it is evil. Artists used to disappoint us by selling out — but that was then. Now, they get #MeTooed.