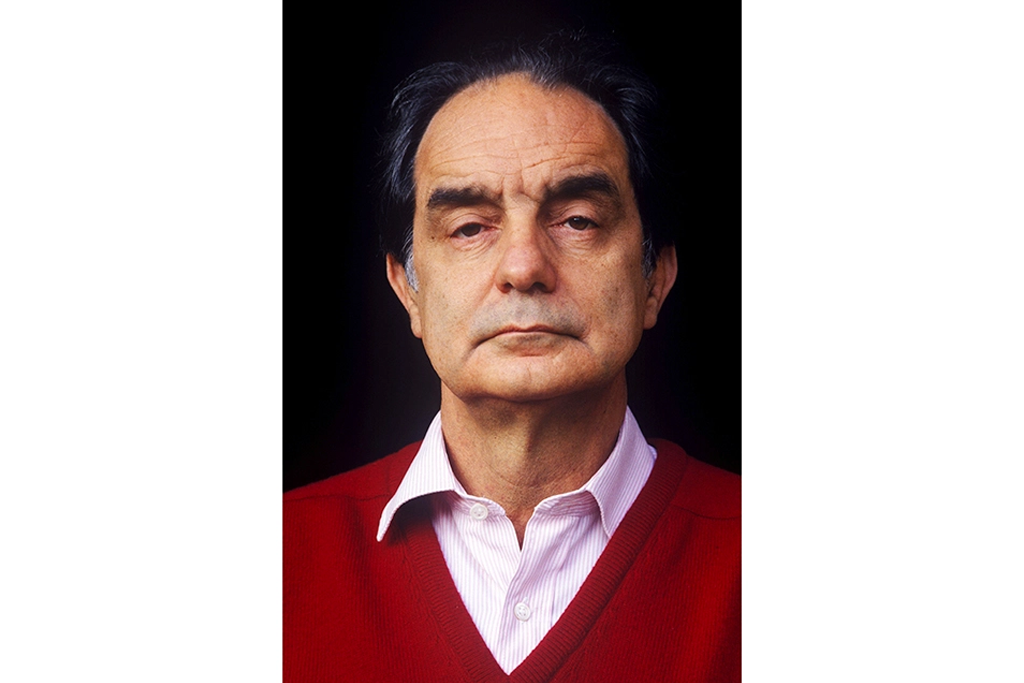

In retrospective mood, just months before the stroke that killed him, Italo Calvino mused on the character of his own writing. “The time has come for me to look for an overall definition for my work,” he wrote. “I would suggest this: my working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight.” Lightness — leggerezza — was the ideal he had striven for. If we think of his best known works in English — the dazzling high-wire acts of Invisible Cities or If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler — it would be hard to begrudge him the satisfaction of considering himself successful in his efforts.

But let’s look at that formulation again: the subtraction of weight. Lightness here is not froth or naivety. Rather, it is sculpted, whittled, pared back from bulkier materials — from Big Ideas, the weight of one’s influences, the pressure to represent one’s own time. The triumph of Calvino’s novels is how they still manage to satisfy these imperatives while presenting themselves as witty, precarious experiments, almost delicate enough to crumble in on themselves.

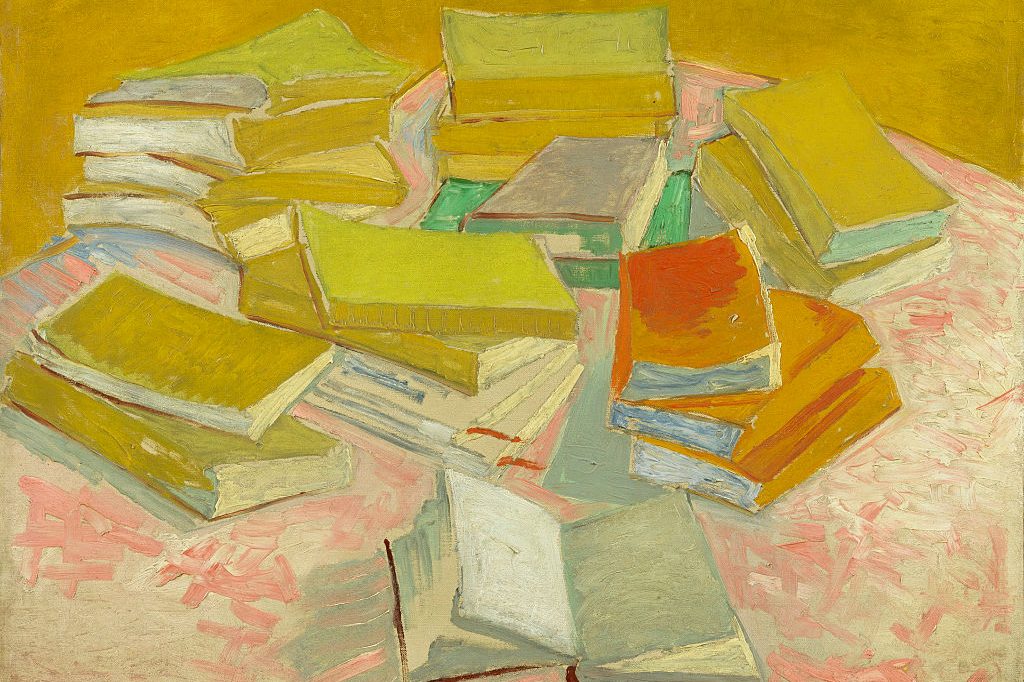

Like his friend Raymond Queneau at Gallimard in Paris, or indeed like T.S. Eliot at Faber, Calvino for most of his adult life worked as a senior editor — in his case at Einaudi, one of Italy’s most important publishing houses. Not only a professional writer, then, but a professional reader too, and an omnivorous, polyglot one at that. To see Calvino in this light — as a reader, from his book reviews, publishing blurbs and letters-page controversies — is to get a sense of the heft that is stripped back or sublimated in his fiction.

For as long as he was a novelist, Calvino was simultaneously a prolific literary critic. The Italian edition of his collected non-fiction runs to some 3,000 pages of crinkly Bible paper. Thankfully, much of this has already been translated, with half a dozen different selections of essays, lectures and reviews appearing in English since his death. Now we have a further tranche, The Written World and the Unwritten World, translated by Ann Goldstein. I have a quibble then with the publisher’s decision to add the subtitle “Collected Non-Fiction” to this new volume when it merely adds to the large amount that is already available. “B-sides and Rarities” might have been more accurate. But there is still good stuff here.

The latest selection loosely follows the arrangement of that Italian complete edition, taking a sample from each of its sections. Most satisfying are the pieces grouped as “Reading, Writing, Translating.” Here we find Calvino thinking and arguing about the state of the novel at mid-century, about what publishers look for in a translator, teasing us — gently, reflexively — about our fetishization of the act of reading. (How many books do you take on holiday? And how many come back with their spines uncracked?) One of the most bracing items here is a spat from 1963 with another critic where Calvino has in his sights a kind of smug or puritanical nihilism in literary criticism that is “pleased with the failure of rationalism.” He signs off by declaring: “I want Beckett’s despair to be useful to those who do not despair.”

Less satisfying is the inclusion of a number of introductory essays written either to publicize a new series, such as Einaudi’s “Centopagine” (classic works of fewer than 100 pages), or to preface anthologies such as Fantastic Tales (from nineteenth-century literature). For all the boundless, borderless learning on display here, there is an element of boilerplate about these pieces, something inevitably formulaic. Uprooted from their original context, all we see is a series of gestures offstage — to E.T.A. Hoffmann, H.G. Wells, Henry James — as Calvino runs us through the Great Works he thinks we should be reading.

The author we find in The Written World and the Unwritten World is serious and scrupling, by turns defensive, jovial, angry and amused. But these are primary colours. What of lightness, that inscrutable blending of playfulness and profundity that feels so characteristically Calvino-esque? Certainly it is here in flashes. In one late article for the newspaper Repubblica he considers Carlo Ginzburg’s famous essay on historical method and ponders the danger of having too much evidence. Calvino describes a South American tribe, expert hunters, whose aptitude for reading the signs around them is so highly developed that no one in the village has any privacy whatsoever. A dropped arrow, an ax resting against a tree, the imprint of a buttock in the grass, all give up their narratives without resistance. The result is less than idyllic. He quotes from an unreferenced research paper: “The village is filled with irritating gossip about men who are impotent or who ejaculate too quickly, and about women’s behavior during coitus.”

I can’t bring myself to check whether the tribe is real or made up; whether Calvino is serving us fiction dressed up as fact in order to make us think about how we do history. Now that would truly be leggerezza.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.