I wonder if Wisconsin has any idea what an international embarrassment it has become? By rights it ought to be an unexceptionable place, little more than the quirky answer to the occasional trivia question: ‘Where is the Badger State?’; ‘Whose state governor shares a name with the singer of “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine (Anymore)?”’; ‘Which US state makes more Swiss cheese than Switzerland?’

Sadly for this unassuming Great Lakes state — pop. six million — it has instead become an exemplar of the kind of official corruption, mendacity, hypocrisy, bovine incompetence and rampant injustice less often associated with the leader of the free world and the beacon of democracy than with Islamofascist republics, equatorial African kleptocracies and other third-world hellholes.

This is all thanks to the Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer, which holds the state’s apparatus responsible for one of the most egregious miscarriages of justice in recent history. Two men have been rotting behind bars for many years for a brutal murder which, it seems increasingly clear, they did not commit. Worse still, it appears that on some level the state’s authorities — from local law enforcement to the attorney general — are aware that the convictions are unsafe, but are in far too deep to backtrack now, and so are fighting all the way to the Supreme Court to uphold the terrible injustice they have perpetrated.

A big claim, I know — and one you probably couldn’t have made after the first series when the waters were still pretty muddy. But this latest, Making a Murderer 2, has acquired a mesmerizing and spectacularly persuasive dea ex machina in the form of Kathleen Zellner. Zellner, a cool, tenacious, Texan-born, Chicago-based lawyer, specializes in correcting miscarriages of justice. Since 1991 she has obtained exonerations for 19 wrongfully convicted men. And over the latest ten episodes, she has left the viewer in absolutely no doubt that her current client, Steven Avery, is similarly, provably innocent.

Avery must surely count among the world’s unluckiest guys. In part one of the series, we saw him being convicted and spending 18 years in prison for a vicious rape he did not commit. Barely had he been released — after the real perpetrator had been identified by DNA testing, allowing Avery to launch a multimillion-dollar compensation suit against the state authorities — than Avery was banged up on suspicion of another crime, murder this time. The evidence against him seemed circumstantial at best and the prosecution’s case, led by a shifty, sweaty, amateurish DA called Ken Krantz, quite risibly threadbare. Yet Avery got life, without parole, all the same.

Even more dubious, if that’s possible, was the conviction of his teenage nephew Brendan Dassey, who had supposedly acted as his accomplice. The prosecution’s case against him rested on a confession he’d given, pretty obviously under duress, to investigating officers who had very audibly coached him into giving the answers they wanted, taking advantage of his youth and low IQ.

After the acclaimed and hugely popular first series — when hundreds of thousands of outraged viewers petitioned the White House, unsuccessfully, for a presidential pardon — various contrarian articles appeared calling into question its trustworthiness. Key facts had been held back, key witnesses hadn’t been interviewed, the editing had given a false impression, and so on.

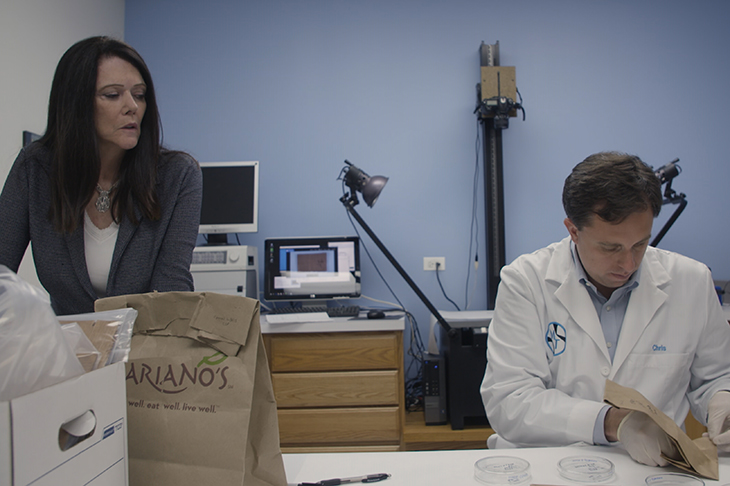

Part two is different, mainly because Zellner is on board. She doesn’t come across as an egregious self-publicist who has hijacked a high-profile case; just someone obsessed with finding out the truth. Piece by piece she builds up her defense: in Arizona a ballistics expert fires a .22 bullet through animal bones the thickness of a human skull to show her how the state’s spent-round evidence — if it were credible — would most certainly have traces of calcium in the squashed lead, visible under an electron microscope. A blood-spatter expert shows how the patterns of gore in the victim’s car aren’t remotely consistent with someone being shot, as the prosecution alleges, in the head. An expert on burned bodies explains how an open bonfire, no matter how tall, is quite incapable of generating sufficient concentrated heat to incinerate a corpse.

You learn so much about forensics, legal process and police procedural that it’s like watching a particularly well-researched and gripping thriller. Except in this case the people are all real, and at the end — spoiler alert — there’s no sense whatsoever that wrongs have been righted, nor that justice has been served. No justice system is perfect. Of course there’ll always be occasions when they get the wrong man. What’s different about this case is that 20 million or more viewers have a better handle on the case’s every detail than the state of Wisconsin. How long do its authorities think they can get away with it? Their intransigence is shaming beyond measure.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.