What kind of loyalty do we owe a robot we’ve paid for — one who exhibits a convincingly human kind of consciousness? Less loyalty than we owe to our own children? But what about to someone else’s child? And do we commit murder if we destroy him?

These are the questions facing Charlie when he spends his inheritance on a robot called Adam. Charlie is a trained anthropologist with an enthusiasm for computers who hopes to give his life meaning by experimenting in ‘electronics and anthropology — distant cousins whom late modernity has drawn together and bound in marriage’. He and his girlfriend Miranda join forces in programming Adam with a personality, playing at parenthood as they create a new quasi-human. ‘We aimed to escape our mortality, confront or even replace the Godhead with a perfect self.’

Quickly, Adam becomes the ‘companion, intellectual sparring partner, friend and factotum’ he’s been advertised as. He performs household tasks, has one mutually pleasurable sexual encounter with Miranda and makes a fortune on the stock exchange. But the moral framework becomes more complex when Adam decides that Miranda should be imprisoned for an earlier moral misdemeanor, at a point when she and Charlie are about to adopt a small boy they’ve grown to love. To make things more complex, the setting is a counterfactual 1982. This is a 1980s with email (already a ‘daily chore’), 250 mph trains (Margaret Thatcher is ‘fanatical about public transport’) and a Falklands war that Britain loses, despite possessing intelligent missiles.

Machines Like Me is an enjoyable, even addictive, read but it’s ultimately disappointing in the way that all Ian McEwan’s novels have been since Atonement. AI matters, and does indeed provoke important ethical questions. The novel is an appropriately moral form in which to confront these and McEwan is in many ways the right person to do so. He’s intelligent enough to understand the science of AI and the philosophy of consciousness. He’s a brilliant novelist, who creates believable characters with ease. From the start, Charlie and Miranda’s relationship has an urgency that makes it easy to care what happens to them. But as with so many of McEwan’s books, it all feels too neat. As in Solar or The Children Act, it’s as though he’s found the subject rather than the subject finding him. This is the novel as dinner party conversation: thoughtful, incisive, witty but frustratingly ephemeral, even if it’s a dinner party I for one would love to be at, especially when one of the guests is doing such a convincing impersonation of Alan Turing, who Charlie gets to know through their shared interest in AI.

Part of the problem is that the book is too dextrous, too pleased with its own brilliance in multiplying moral dilemmas so swiftly. At the same time as worrying about what it means to be cuckolded by a machine (‘he was my expensive possession and it was not clear what his obligations to me were’), Charlie ponders the ethics of the Falklands War (Miranda is convinced Britain was right to invade in order to save the islanders from a dictatorship), the question of whether ends justify means in convicting a rapist, and the relative value of truth and love. It’s clever that McEwan has found a form that allows these problems to be interwoven so elegantly, but it’s also a weakness, because it feels as though the characters are being sewn into the tapestry without agency.

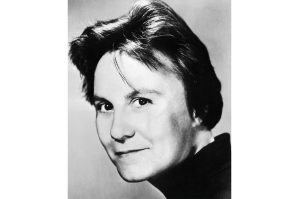

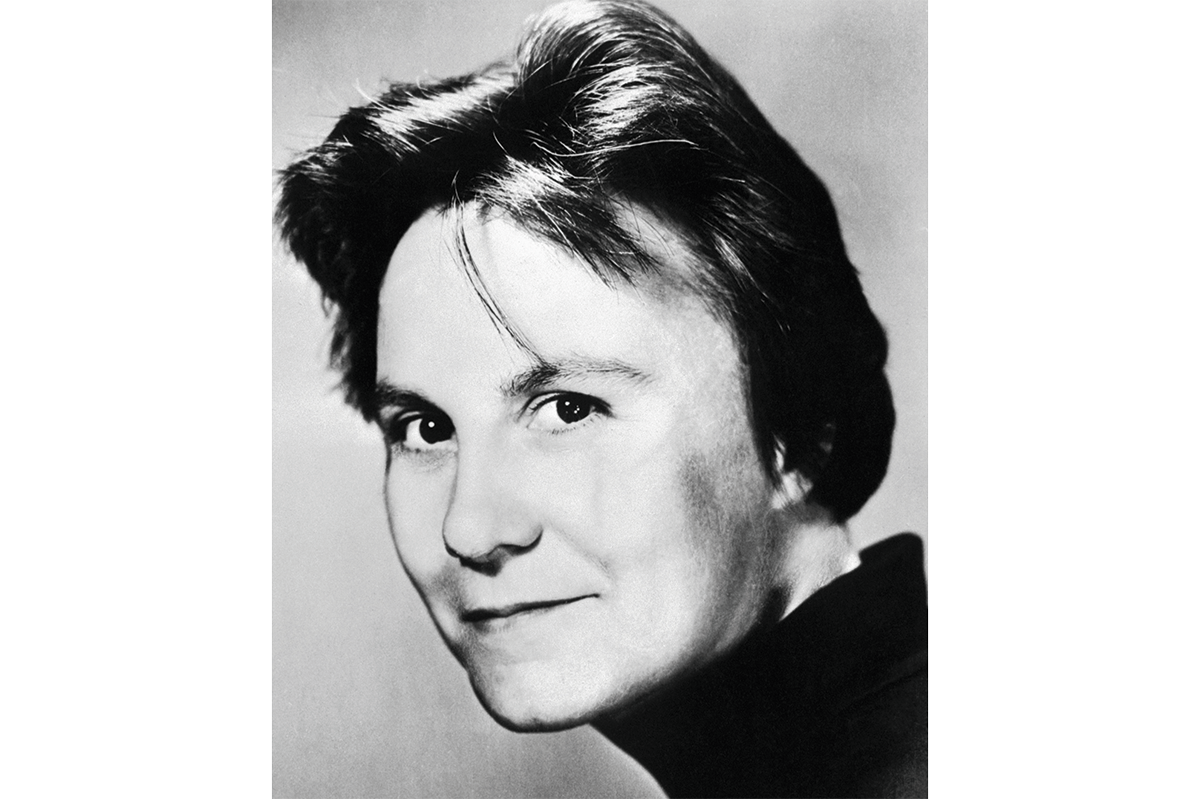

While reading, I thought quite often about how other moral novelists would have approached this. George Eliot, Tolstoy, even D.H. Lawrence might have been watching from further away to see what the characters do, prepared to draw moral conclusions from the drama while appearing to observe it unfold organically and therefore randomly. Eliot might have found it hard to resist a few learned digressions of the sort McEwan offers, when he explains the ethical conundrums provoked by driverless cars or gives a quick history of disease. But she’d have allowed more moments when the plot slowed, letting life continue for its own sake.

At one stage, Turing explains to Charlie that the most difficult thing for robots is that, however intelligent they are, they can’t understand how humans endure contradictions: ‘We live alongside this torment and aren’t amazed when we still find happiness, even love.’ In his best novels, McEwan has shown us what life at its most richly and painfully contradictory feels like. Machines Like Me reminds us that McEwan is a once-in-a-generation talent, offering readerly pleasure, cerebral incisiveness and an enticing imagination. But we need him to leave his diagrammatic, even robotic comfort zone and trust in the messiness that characterizes both human life and the novel at their richest.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.