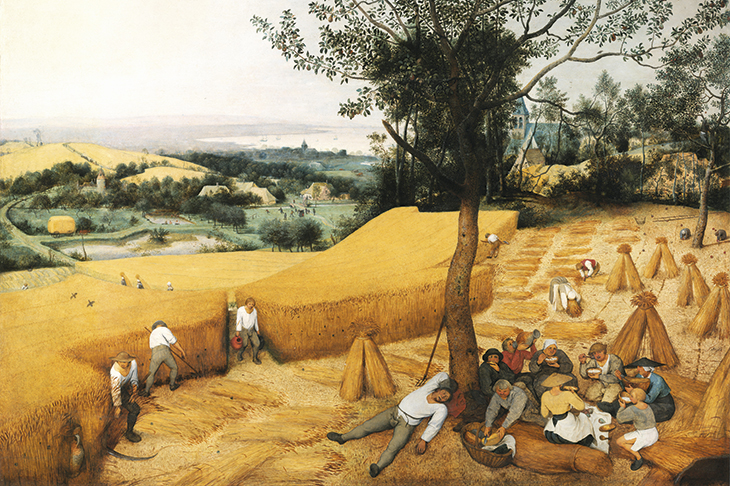

There is a vogue at the moment for books which use art as a vehicle for examining the writer’s wider life and interests. Toby Ferris will certainly not have seen this as in any way an autobiography, but what it essentially does is use a quest for the 42 surviving paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder as a starting point for an exploration of anything and everything, from the death of a friend to art history, family history, philosophy, anthropology, mathematics, music and paragliding.

The result of this — what Ferris calls his Bruegel Project — is an intricately plotted book that is by turns stimulating, moving and sometimes mildly pretentious. The 13 chapters are organized not in chronological order of the paintings, nor geographical order of the author’s visits, but relate either to objects and events in the paintings — gallows, beggars, bears, fire, census, massacre —or to qualities such as ‘cold’ that license the author to cut loose.

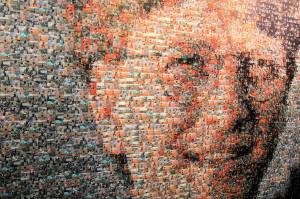

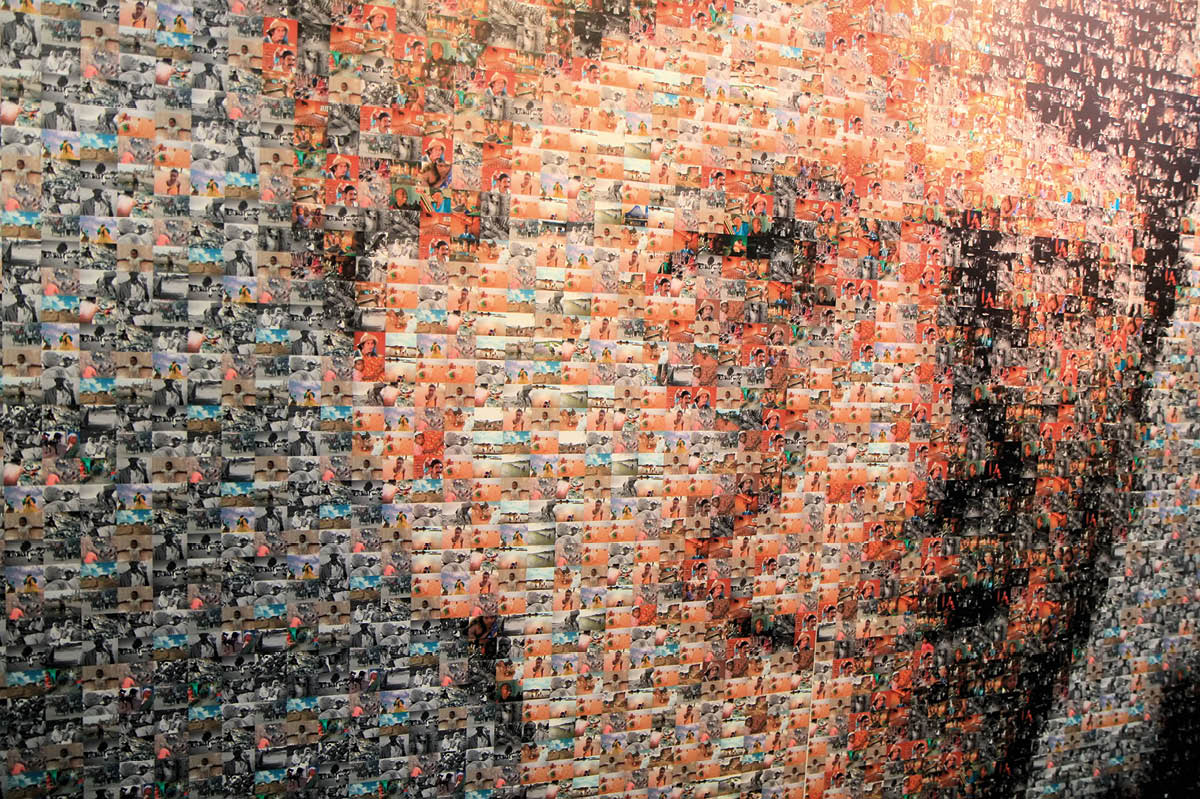

Take Chapter XII for instance, entitled ‘Crowd’. Ferris starts with a visit to Budapest with his brother to see ‘The Preaching of John the Baptist’ in Buda Castle. Another half dozen paintings are considered in detail. He discusses crowds of tourists, crowds in galleries, the psychologist Robin Dunbar’s theory of numbers in the context of social relations, the significance of hats, the persecution of gypsies in the second world war, a study of the flocking behavior of birds and fish, the career and experiments of the art historian Hans Sedlmayr, the quality of uncanniness in Bruegel’s work and the little we actually know of Bruegel’s life. On to lunch in the canteen of the Ministry of Justice in Vienna, military uniforms, Bruegel’s placement of groups of figures in or on landscape, Ferris’s brother’s book on Beethoven and much more.

‘I have very little interest in biography,’ he says, but among the welter of digressions that fill this book one persistent theme is the story of his parents. After wartime service in the Fleet Air Arm his father worked for most of his life for the General Electric Company, where his career more or less stagnated. A damning appraisal, kept until his retirement, stated that ‘under no circumstances should he be considered for further promotion’. In about 1978 Ferris senior wrote a single rather sobering line in a huge diary: ‘It is said that in every life there is one story. This is mine.’ The rest of the diary was blank. The author’s mother’s slow decline into dementia — and that all too recognizable world of daytime television — is also a melancholy motif. He compares the loosening of her mental grip to what he describes as the ‘collective insanity’ of Bruegel’s ‘Netherlandish Proverbs’.

He writes tellingly of the loss of parents, ‘the loss,’ he says, ‘not just of individuals that we love but of a communal manner of being’. But for all the family history, the real strength of this book lies in Ferris’s infectious enthusiasm for Bruegel, and every arcane offshoot loops back to the artist’s work. He is brilliant on the detail, on the slight variations that denote the master from the copyists, on the realities of peasant life, on the marginal figures; and Bruegel of all painters is the most rewarding subject for this sort of scrutiny. The book is nicely illustrated, but still cries out for more —a catalogue raisonné or a tablet feels more or less essential.

But the Project is compelling in any case. We’re with Ferris as he approaches each gallery with trepidation, wondering if the rooms will be open, if the paintings will still be there. He paces the dimensions of the space, notes the relation of the paintings to each other and then looks. And he is keen on the business of looking. How long is long enough to look at a painting?

‘When am I done with looking? I will never be done. There is no completion to be had. No point of closure. To stand in front of a painting such as this [‘The Hay Harvest’] is to be caught in a loop of contemplation. You can only at some arbitrary point summon the will and walk away, knowing that the instant you do, memory will already have started on the one hand to fade, and on the other to coalesce.’

Heavy-going, perhaps, but Ferris is also good at making us look with a new eye at familiar paintings, and readers can ask for nothing more of an art book.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.