In the thriller Inside, an art thief named Nemo (Willem Dafoe) breaks into the New York penthouse of a renowned architect and collector. Once there he is all business, liaising with an unseen collaborator via walkie-talkie rather than stopping to admire the art.

It is no accident that the paintings he is there to steal, by the Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele, depict tortured souls, with emaciated frames and paper-thin skin. By the end of the movie Nemo will be a physical manifestation of Schiele’s works: a man living in wretched limbo, psychologically tortured and physically deplete.

Directed by Greek filmmaker Vasilis Katsoupis, Inside is a reworking of the one-man survival drama, at once euphoric and painful to watch. Unlike hits such as Cast Away, however, Nemo is trapped not in the great outdoors but in a man-made fortress. When he attempts to leave with his heist, the security system malfunctions. His colleague on the walkie-talkie abandons him. There is no running water, no food, and the heating is slowly, unbearably, ticking up. For months, Nemo’s only company are the artworks, which stare down at him. Beautiful, priceless, uncaring.

With no other people in the film, aside from an occasional hallucination and the staff Nemo watches moving around the common areas on a CCTV camera, the art must do some serious heavy lifting. Each piece becomes a character in itself: reflecting Nemo’s increasingly desperate state of mind; serving as company and conversation. At certain points — such as when he uses a sculpture to break open the cold room — they enable him to survive.

Thirty-eight artworks by twenty-five artists and collectives appear in the movie, pulled together by Italian curator Leonardo Bigazzi. “It’s a way of treating art on the screen I haven’t seen before,” one of the artists later told Bigazzi. “Many times, art is present in a way that is just decoration. Here every single work is there for a reason.”

Bigazzi, forty-one, took just over four months to conceive and organize the collection, working from Florence, where he lives with his partner and two children. “I still don’t know how the fuck I managed to make it happen,” he laughs, shaking a mass of tousled black hair when we meet for breakfast in Manhattan.

Charming and effortless, his easy personality and good looks — he arrives for our interview in black rectangular glasses matched with monochrome navy pants and sweater — belies the level of manpower it took to curate the collection for screen. Contracts had to be drawn up. The art transported. Expectations managed.

While some pieces were commissioned for the film, others were replicas (once filming ended these were destroyed). A couple that appear are originals. Artists, so used to micro-managing every aspect of how their work is made, labelled, and displayed, gave up control. “I was worried about the artists’ reaction [to the film],” admits Bigazzi.

Bigazzi’s own inspiration started with Ben Hopkin’s script. The artwork in the increasingly hostile penthouse (surely every person’s nightmare of a smart home gone rogue) must, on the one hand, be a physical manifestation of the absent owner and showcase his ostentatious wealth. On the other hand, it had to lend an aesthetic mood to the film — providing beauty for its own sake — and create a journey for Nemo to navigate.

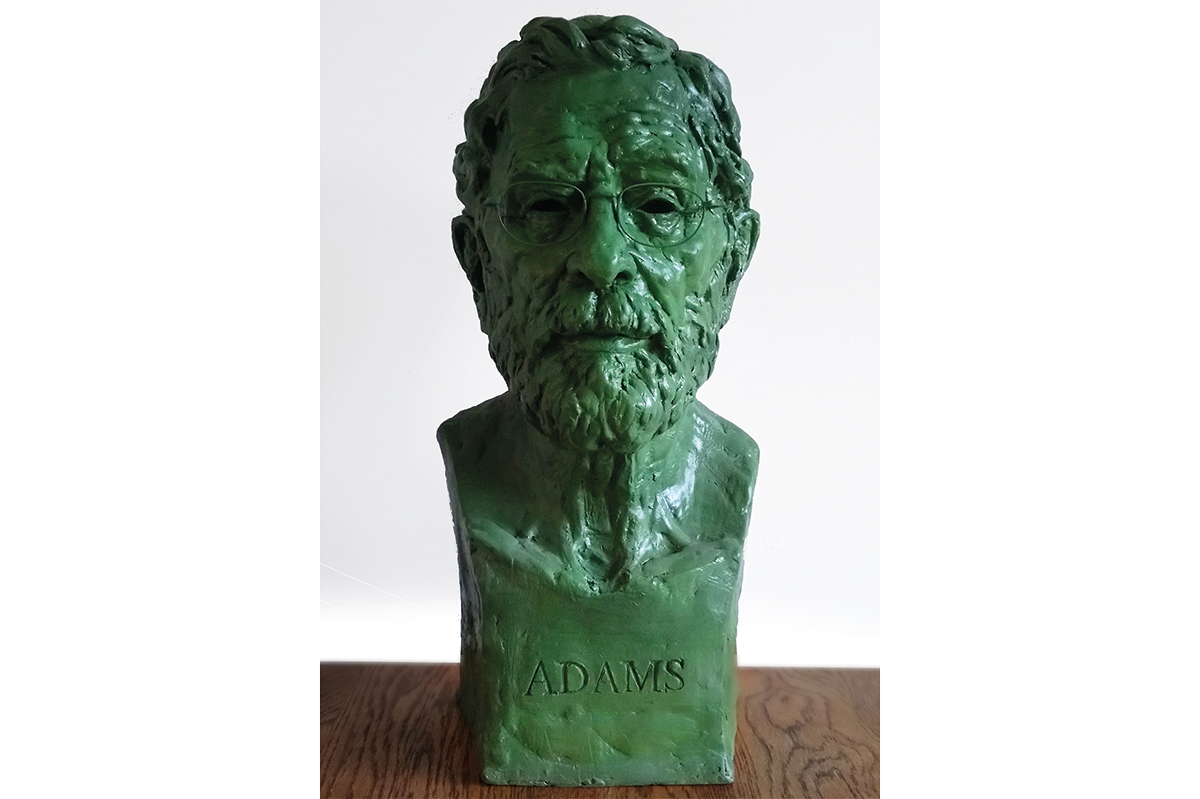

One example is the penthouse owner’s portrait, which Bigazzi commissioned from German photographer Albrecht Fuchs. In the picture the architect stands nonchalantly in a green velvet suit, as a majestic dog lies at his feet. His young daughter perches on the edge of a sofa in a soft purple dress and white socks, her hands folded meekly in her lap and her long blonde hair falling over her shoulders. She looks angelic.

“That image conveys this idea of the collector being a very powerful man — even the daughter is one of his objects. She’s distant, she’s beautiful, there’s no empathy between them,” says Bigazzi. In the film, Nemo defaces the portrait: drawing horns and a tail on the collector and a crown on the girl, replete with a thought bubble exclaiming: “Oh Daddy!”

It’s a wince-inducing moment: the crass defacement of art. And yet somehow necessary for Nemo’s own mental battle, as he pits himself against his absent nemesis and asserts his power in a strange, belligerent environment.

Towards the end, Nemo frees another work, throwing it to the floor. “Untitled” (1999) is a print of a performance piece by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan who attached his own gallerist, Massimo De Carlo, to the wall for hours with duct tape. (Massimo later collapsed and was rushed to hospital.) It is known colloquially as “A Perfect Day.”

In the image, a suited Massimo has his eyes closed (in ecstasy or pain, it’s unclear) and the tape spirals out from his body as if he is wearing angel wings. When Nemo travels to the penthouse he, like the gallerist, believes he is the one in charge. But when ensnared, he is now “exhibited, somehow given to the gaze of the audience,” notes Bigazzi.

Inside is a rare film: one that takes art seriously and understands its conceptual power. But it also watches — agnostic, or perhaps gleefully — as Nemo systematically destroys the very artwork the film elevates. I love art but found myself siding with the plunderer: chaos is preferable to the restrained, self-congratulatory penthouse and the strained values it pedals.

I ask Bigazzi if he is worried that rather than bring art to a new mass audience, the movie only reinforces a common view of the contemporary artworld: that it is aloof, elite, inaccessible, and for the fabulously wealthy only.

“It’s a duality in the film,” he agrees. “I trust art to always find its way to raise certain questions.”

One question is whether Nemo himself can become an artist, forging his own path, however unorthodox and however unvalued by the powers that be. Who, after all, gets to decide what is art and what is not?

It’s a thought, like his escape, that remains deliberately obscured. Days after the credits rolled, I couldn’t stop thinking about one work: a still from the video “Centro di permanenza temporanea” (2007) by Albanian artist Adrian Paci, which depicts an air stair crammed with people lining up to board an airplane, set against a picturesque blue sky.

Yet there is no plane. They will go on no journey. They wait patiently above a void. It is a staircase to nowhere.