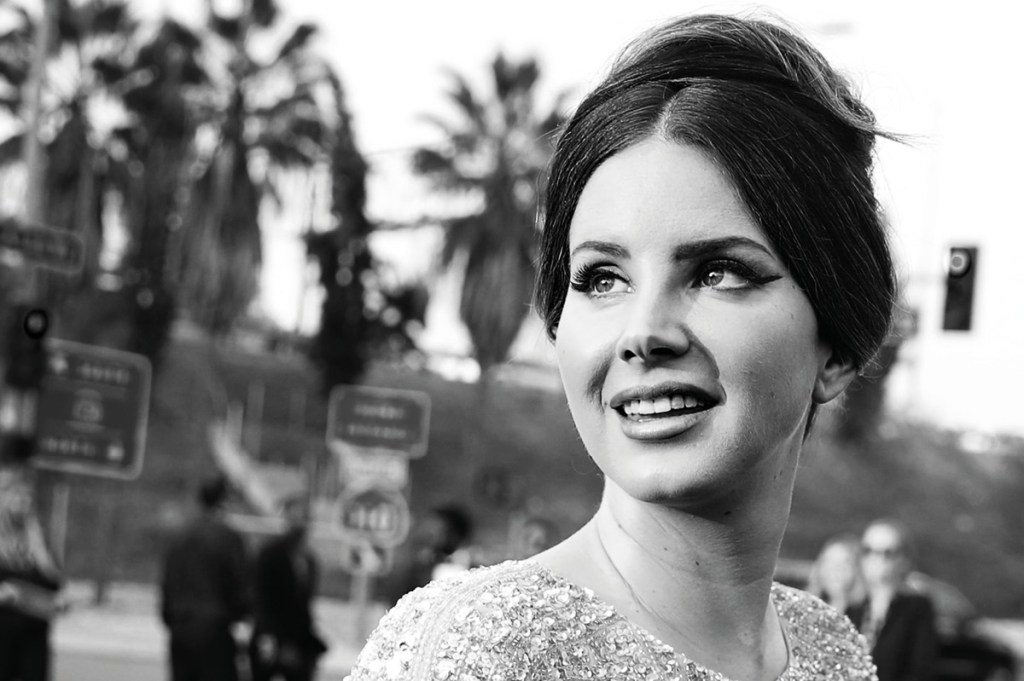

The title song of Lana Del Rey’s ninth studio album, Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd, opens in a style now typical of the thirty-seven-year-old singer-songwriter. Amid the swelling string accompaniment and slow beat, the artist sings “fuck me to death, love me until I love myself.” So far, so in keeping with the musician who made her name with the dark, sensuous songs of 2012’s Born to Die (“my old man is a bad man, but I can’t deny the way he holds my hand”) and 2019’s Norman Fucking Rockwell! (“Goddamn man-child, you fucked me so good I almost said ‘I love you’”).

This album — Del Rey’s fourth in four years — is, in many ways, a continuation of the artist’s signature mix of faux-country, Americana nostalgia, glamorized sadness and confessional intimacy. Having moved away from the “world-building” type of album found in Norman Fucking Rockwell!, the Del Rey of Blue Banisters moved into the far more prosaic territory of singing about pandemic weight gain (“the only thing that still fits me is this black bathing suit”).

A year on, Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd has a similar feeling of near-spontaneous immediacy, but is drawn to more spiritual subjects and ideas. After the a cappella-style opening to “The Grants” (released as a single before the album), a voice reaches out: “So you say there’s a chance, for us / should I do a dance for once?” What appears initially to be a song about a failed relationship is something far deeper, suffused with influences from scripture and gospel music as Del Rey asks “Do you think about heaven? / Do you think about me?” As a paean to the religious and folk-music culture of the American West, it’s a wonderful success. But as a dramatic opening to an album, it leaves any listener slightly unsure of what might come next. “Sweet” is, as its name would suggest, pure saccharine, while “A&W” — also released as a single — is dark, complex and knotty. Over the space of seven minutes, Del Rey covers everything from “I haven’t done a cartwheel since I was nine,” to “this is the experience of being an American whore.” Part bildungsroman, part indictment of contemporary sexual culture (“If I told you that I was raped / Do you really think that anybody would think I didn’t ask for it?”), the song is confessional, angry and powerful — Del Rey at her best.

After namechecking both her “pastor” and folk guitarist John Denver in “The Grants,” Del Rey is keen to draw attention to her influences. After “A&W” come the musical, angry tones of pastor Judah Smith (who preaches at Churchome, a Los Angeles-based church beloved of celebrities) speaking about lust and desire. A few tracks later, the songwriter Jon Batiste has another interlude: his voice and laughter (“I feel it heavy”) are layered under piano chords and Del Rey’s vocals.

While she may have not gone in for the creative, cinematic world-building of Norman Fucking Rockwell!, this is still an album that has its own atmosphere, its own touchpoints and references. In “Kintsugi” — named for the Japanese school of repair work that leaves mending visible — Del Rey even riffs off Leonard Cohen’s spirituality, singing repeatedly “that’s how the light shines in / that’s how the light gets in.”

Did You Know is also an album with a high number of duets and other artists featured: Del Rey sings with SYML in “Paris, Texas,” with Father John Misty in “Let the Light In,” Bleachers in “Margaret” and Tommy Genesis in “Peppers.” The most successful of these is “Let the Light In,” where the two artists’ voices layer to produce a track so vocally rich that it almost lends a new perspective to the most predictable of Del Rey’s themes: a country-esque romance.

There are patches of novelty on the album: alongside “A&W,” “Fishtail” is a lyrically complex track with memorable, near-poetic images (“swinging in a nightgown underneath the old oak tree”), while “Fingertips” is a five-and-a-half-minute tour de force of narrative storytelling. But moments of sameness drag the album down into staleness and sterility. “Candy Necklace” borrows the single-voice sadness of Del Rey’s famous tracks about monied, gilded America; the final track, “Taco Truck x VB” is little more than an extended remix of 2019’s “Venice Bitch.”

This album will undoubtedly be a success — and it is studded with tracks worthy of acclaim — but it is hard to avoid the feeling that it could have been better. Del Rey has moved part of the way into novelty, experimentation and a new vocal landscape, but is, perhaps, too attached to her past output to render it entirely satisfying.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2023 World edition.