Everyone has a type they can’t resist. For the writer Kazuo Ishiguro, it’s old men. Old men secretly worried they’ve spent entire lives on the wrong side of history. Old men born in a world of certainty, transplanted to a different, more dubious one. Old men asking themselves, as so many of us will do (if we haven’t already): “What was it all for?”

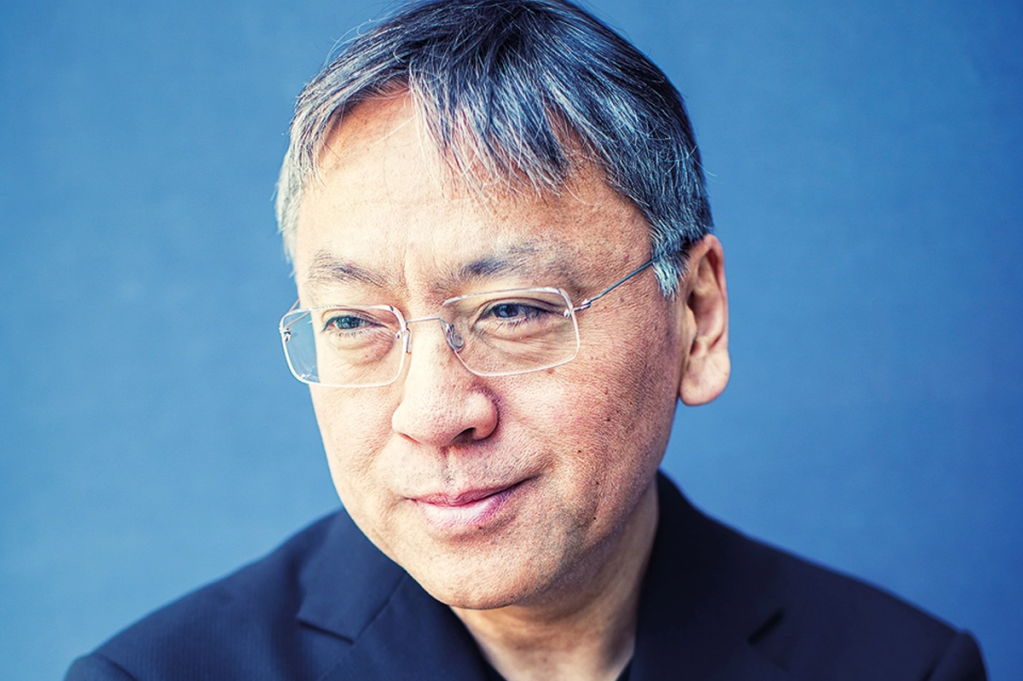

But as I wait at the offices of a PR firm in London’s West End to interview Sir Kazuo about his new film with Bill Nighy, Living, I can’t help but wonder what unlikely preoccupations these are for arguably the nation’s greatest living literary talent. Those of us with humdrum lives may daydream about winning a Nobel Prize. But in Ishiguro we have a Nobel laureate who, perversely, can’t stop fantasizing about a life of mediocrity or failure.

In his Booker Prize-winning novel The Remains of the Day (1989), it is the English butler Stevens (memorably portrayed by Anthony Hopkins in Merchant and Ivory’s film version) who looks back on a life of service only to be nagged, after World War Two, by the feeling that he had all along served the wrong master — a Nazi collaborator. In Ishiguro’s earlier novel An Artist of the Floating World (1986), the aging painter, Ono, broods on much the same, in post-fascist Japan. These themes now take a new form. Though directed by the South African filmmaker Oliver Hermanus, Living was very much Ishiguro’s brainchild, a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (1952) that tells the tale of Mr. Williams (Bill Nighy), a terminally ill bureaucrat in 1950s London, whose last wish is to make a difference after a lifetime of conformity.

As Ishiguro arrives, exactly on time, a small party for film industry types is happening in the lobby. In a rain-sodden trench coat, the kind favored by men of a certain generation, he looks much the outsider. Though no stranger to bohemia, Ishiguro’s imaginative affinities somehow lie with a different sort of person and scene, the sort that prompted the New Yorker to recognize in his work a quality of “almost punitive blandness” (intended, apparently, as praise).

“I thought I would have an ordinary life,” Ishiguro tells me, recalling his childhood in the English commuter-belt town of Guildford, where he arrived aged five from bombed-out Nagasaki in the late 1950s. “We lived in this little cul-de-sac, where my mother lived in the same house until she died; it was like a small community.” His Japanese family was “treated very well, despite this recent history of enmity,” and his experiences were typically middle class. “I even sang in the local choir,” recalls Ishiguro, who also attended a grammar school and, later, university in provincial towns (Canterbury, Norwich) rather than the Oxbridge conveyor belt.

Around him all along were those ordinary, strait-laced, bottled-up people, who had served king, country or empire only to find their values placed under a moral microscope — not least, eventually, in Ishiguro’s own work. “What would I have done,” he admits to asking time and again, “had I been of their generation?” His characters — Stevens, Ono and now the timeserving clerks in Living — all pass the buck. “I think it’s complacent to say as a member of the generation that came afterwards that we would have never been like this.”

Fascination with his elders came early. There’s an image Ishiguro describes in his 2017 Nobel lecture of how, taking a suburban train to school, he “shar[ed] the carriage each morning with ranks of men in pinstripe suits and bowler hats, on their way to their offices in London” — a vision of the past reminiscent of Larkin and his “fools in old-style hats and coats,/ Who half the time were soppy-stern.”

The memory wouldn’t leave Ishiguro, with each passing year becoming a more potent picture of a vanished world, until it ended up as the defining visual motif of his screenplay for Living. The lives of the civil servants portrayed in the film all have the regularity of a train timetable — no unscheduled stops, no detours — and the sound of the wheels trundling along the tracks drums home what pointless careers they have as cogs in the bureaucratic machine of London county council. It’s wonderfully evocative. (Still, Ishiguro kids himself: “I don’t know how to write screenplays.”)

Approaching the end, Mr. Williams realizes what Stevens in The Remains of the Day also comes to suspect: that they lived up to their quintessentially English ideals, the bowler-hatted gentleman and the black-tied butler, only to find themselves in an England bewilderingly indifferent to everything they took pride in. What was at the bottom of Ishiguro’s precocious sensitivity to this predicament, which he started writing about in his mid-twenties, long before any personal experience of it himself. “That just was an instinct I had when I was young,” he says.

But what if it were the experience of migration that had grounded it all? Was Ishiguro not, aged only five, displaced from one world to another? To become estranged from the world around oneself — is this not what happens to the old men who captivate him? “I think there’s something in what you say, “the past is a foreign country” and all that,” though he later reflects that “very few English people ask questions about the past.”

But Ishiguro observes a vital difference between “emigrating to old age,” and simply emigrating: a difference in the “appetite” for new things. Immigrants still have one, and are celebrated for it; old men have lost theirs, so we despise them. “People like me in my sixties are being asked to think about the world in terms of climate change, rather than the old arguments about communism vs capitalism,” says Ishiguro. “But too much energy has already been spent understanding the world in one set of terms.”

It’s a feeling that presents a challenge to any aging artist. In his Nobel lecture, Ishiguro asks: “Can I, a tired author, from an intellectually tired generation, now find the energy to look at this unfamiliar place?” His own body of work provides an interesting answer. What’s so subversive about the way he confronts this unfamiliarity inflicted by time on the old is that, even if Living may be “a fictional recreation of a Britain, remembered from childhood, very rapidly disappearing,” Ishiguro has developed a method of envisioning the past free of nostalgia, where the stories we tell about it become instead objects of mistrust. “We’re all unreliable narrators, not just to other people, but to ourselves,” he explains.

Ishiguro is referring to a technique that he is famous for mastering in his novels. But isn’t it harder to get the camera to deceive or evade? “This is one of the differences between cinema and written fiction,” Ishiguro agrees. “It’s harder to have unreliable narrators, just as it’s difficult to get the haziness of memory on the screen.” He cites Kurosawa’s Rashomon as a rare film that pulls it off. Ishiguro has publicly stated — after being quizzed enough times — that he isn’t much influenced by Japanese literature, but what about Japanese movies?

He lights up. “I was being taken to the cinema in Nagasaki when I was four,” he reminisces, “and among the movies that came out of Japan in the 1950s, there was a ridiculous number of masterpieces.” It turns out this has been central to his work, though underexplored in critical appraisals of it. “The Japanese filmmakers of that period had a huge effect on me. When I started writing fiction back in the early 1980s, I was copying Ozu,” he confesses, referring to the director of Tokyo Story (1953) which he explains also portrayed “older people displaced in the modern world.” But even more than that now familiar theme, it’s Ozu’s invention of a style perfectly suited to that culture of restraint — slow, dignified, elliptical — that has been most inspiring. “When I write even in a more western environment,” Ishiguro remembers thinking to himself, “I’m going to have the courage to go really, really slowly.”

At the start of his career, Ishiguro says, it wasn’t clear if he was going to be a screenwriter or a novelist. For a while he earned his living from the former but not enough films got made, and so cinema’s loss was literature’s gain.

His involvement in the film industry persists though, with seven projects in development, including at Netflix, on top of being a judge at this year’s Venice Film Festival. Salman Rushdie once observed how Ishiguro’s “sensibility was not rooted in any one place, but capable of travel and metamorphosis.” Neither is it rooted in any one form of creativity, and if, like Mr. Williams, Ishiguro gets one last chance to make an about-face, I wonder if it might be from novelist to filmmaker.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.