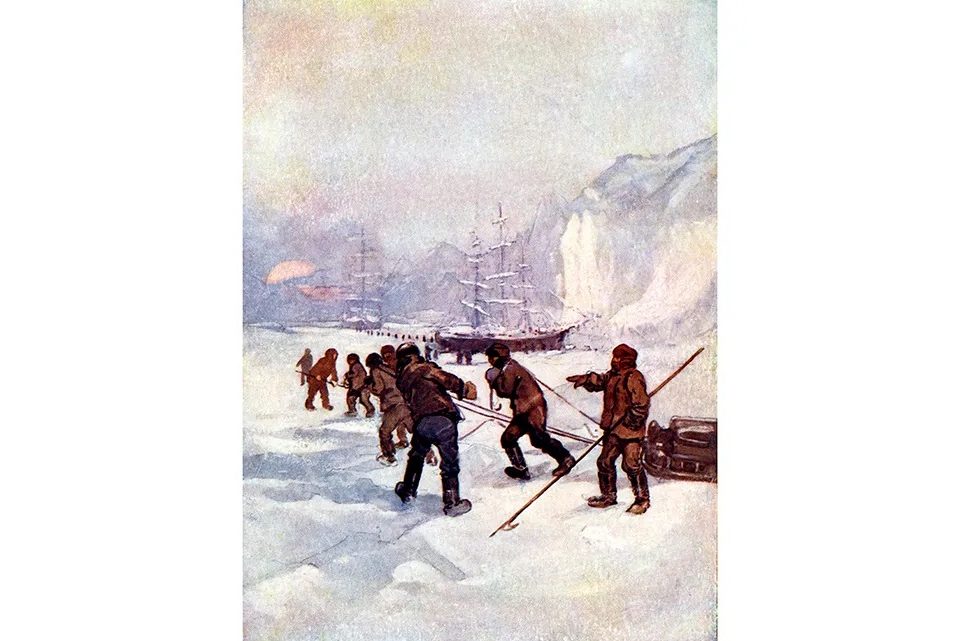

If you could resuscitate a hunk from history, who would you choose? The secretive Whitehall ministry in Kaliane Bradley’s striking debut is working on time travel, facilitating the removal of various Brits from their own era to (roughly) ours. The candidates were all due to die anyway, so the risk of altering history is minimal. Curiously, the scientists do not pick Lord Byron, but a naval officer on the doomed Franklin expedition to the Arctic, lost in the search for the Northwest Passage.

Each time traveler is assigned a “bridge” — someone to both monitor and help them adapt to twenty-first century London. Lieutenant Graham Gore is paired with a young female civil servant of mixed white and Cambodian heritage. “I don’t say my name, even in my head,” she announces, but as their relationship, cooped in a shared flat, develops, he dubs her “Little Cat.” He has to be trained not to use the word “negress” of Semellia, another bridge, and unhesitatingly recalls his own brushes with the slave trade. Whisked from the 1840s, he is not overly impressed with the modern world, scorning the “diorama” that shows “people at their most wretched.” “No one’s forcing you to watch East Enders.” Learning about climate change, he asks: “Can you go back and stop it from happening?”

The other “expats,” as the visitants are known, comprise Arthur, a harrowed, gay officer from World War One who knew Wilfred Owen; an arrogant captain due to die at the battle of Naseby; an ostracized seventeenth century lesbian; and an Englishwoman caught up in Robespierre’s Terror. Alas, Bradley seems uninterested in the latter’s Parisian ordeal and she swiftly disappears from the narrative.

Little Cat falls hard for sexy Graham, who, for an unmarried man who has been at sea since the age of eleven, gets the hang of things surprisingly quickly, despite retaining a few Victorian hang-ups. But their passion is soon interrupted by temporal ructions, moles in the ministry and, of course, portal-hopping villains. As for how time travel actually works, Bradley adopts the “Frankenstein” method of scientific exposition (retorts, glass valves? Something about lightning?). “Don’t worry about it,” avers Little Cat. Narratives, counter-narratives, twists and frenzied bouts of cleaning up the timeline ensue. I’m not certain I followed all this or was even meant to, but amid the climaxes and explosions there are interesting discussions between Semillia and Cat about who gets to write history and how they go about it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply