This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

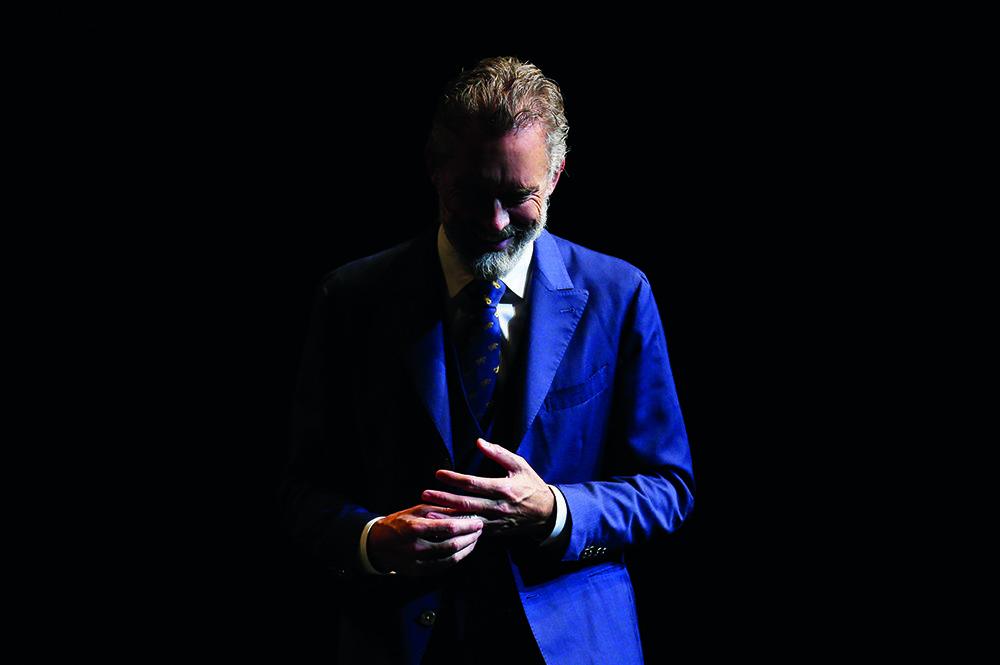

If Jim Proser’s goal in writing Savage Messiah was to convince people to take Jordan Peterson seriously, I am afraid he has failed miserably. Peterson, for those without an internet connection, is a Canadian psychologist who rose suddenly to fame after he posted a video on YouTube criticizing a bill that proposed criminalizing speech against transgenderism. In 2018 he published 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, which has sold several million copies. He has confounded undemanding television hosts like Cathy Newman, but he has also debated Sam Harris and Slavoj Žižek, all while keeping up his popular podcasts and lectures.

Peterson is a careful defender of free speech and an eloquent but firm father figure to men (and some women) who find themselves caught in unsatisfying lives. He has defended the biological differences between men and women, and has spoken out strongly against wrongheaded policies on race and sex. He is serious and sober-minded.

Proser, alas, is not. He is a fan. He hopes readers will find ‘some solace’ in Peterson’s words, ‘some inspiration’ in his life and ‘some relief from…undeserved suffering’; deserved suffering, in the Petersonian system, being their responsibility. Savage Messiah is at its best when Proser shows us how Peterson has helped real people, dealt with suffering in his own life and demonstrated courage in times of controversy. If only Proser had stuck to these, we might have had a short, useful, mildly interesting biography of an early 21st-century icon who will, like most of us, be forgotten in 50 years, or dimly remembered in the way of Joseph Campbell, who was the Jordan Peterson of the Sixties. Instead, we have biography as mythology, with Proser writing his own version of Peterson’s Maps of Meaning and Peterson as the solitary hero who ‘slays the dragon of chaos’.

‘He was Orpheus descending into hell,’ Proser writes as Peterson spends a year abroad in his early twenties; ‘he was Odysseus traveling through the land of the dead.’ When Peterson does some reading, he is ‘Jason on his dangerous voyage with Argonauts to bring back the golden fleece of knowledge’. When Peterson overcomes anger and drinking problems as a young man, Proser compares it to Jesus rejecting Satan in the desert. The Prince of Darkness, Proser writes, ‘did not take Jordan’s rejection lightly’, whatever that is supposed to mean.

Remember Occupy Wall Street? A couple of thousand protesters with no coherent objectives camped out in New York City’s Zuccotti Park for two months, marched through the Financial District once, and then ate pizza. I didn’t realize it at the time, but if Jordan Peterson hadn’t got involved, Occupy, which Proser calls a real threat to ‘global capitalism’, would have meant the beginning of the end of the free world: Peterson took on a ‘burden close to that of Atlas’s’ and was ‘about to carry the modern world on his shoulders’. He defended ‘traditional western European Enlightenment values’ against ‘youthful revolutionaries who were desperate to breach the walls of western tradition with opposing, collectivist values’.

To make matters worse, these young radicals apparently had the help of Russian television and its $150 million budget. Peterson, however, had only his wits: ‘Jordan was unprepared and overmatched in everything except commitment. He had no organization, no allies, no funding, and no strategy.’ Nevertheless, he persisted and ‘charged into the fray’ of ‘tweets, hundreds of YouTube videos, and Quora questions’, fending off ‘hordes of red-faced, outraged enemies beyond his imagination’ in the comments box.

Proser does provide a helpful summary of Peterson’s early years and youthful dabbling in Canada’s New Democratic Party politics. He notes Peterson’s churchgoing as a child (at the Protestant United Church of Canada, though Proser refers to Peterson as a ‘lapsed Catholic’ for some reason). Proser also highlights Peterson’s early interest in Nietzsche and Marx, his discovery of Solzhenitsyn and Dostoevsky, his unwavering commitment to telling the truth — both to himself and others — and, perhaps most significantly, his debt to Carl Jung.

But this is not an intellectual biography. It lacks any serious evaluation of Peterson’s thinking or popularity. We’re told that Peterson joined the ‘immortals of his field’ when, like Einstein, Jung and Bertrand Russell, he published a book with Routledge. Proser calls this the ‘pinnacle of achievement in many academic circles’. This will be news to many professors. We’re also told how Peterson lost weight by cutting out gluten and how his Patreon donations went from $1,000 to $60,000 a month in the span of two years.

None of this is to disparage Peterson’s accomplishments. Proser writes movingly about Peterson’s early work with alcoholics at McGill University’s Douglas Hospital, and he describes people walking up to Peterson at a café to tell him how much he has helped them. In his lectures, Peterson would occasionally break down when talking about cases or people he has encountered. There is one particularly touching story about a four-year-old boy Peterson’s wife used to watch after school who refused to eat because his mother had never bothered to teach him. Peterson’s wife shows him how to use a spoon, and the boy follows her around ‘like a puppy’ — not unlike some of Peterson’s young male admirers, themselves intellectually and emotionally malnourished.

For speaking honestly, Peterson has endured the anger of college students and administrators, as well as leftist digital mobs. He continues to say unpopular things, not because he hopes to benefit from being provocative, but because he genuinely believes they are true. Earlier in 2019, Peterson left Patreon after the sponsorship website banned Sargon of Akkad, the online irritant known to his parents as Carl Benjamin, for hate speech. Whether you agree or disagree with Peterson’s decision to leave Patreon, it no doubt cost him. But this is hardly tantamount to ‘saving western civilization’.

Proser ignores the ways in which the Peterson phenomenon might also be a symptom of the West’s decline — in Peterson’s Nietzschean interest in myth and his determination to plumb it, like the proto-fascist Gabriele D’Annunzio and the Surrealists before him, in search of some primordial self.

People in the West today are generally far less interested in living good lives than happy ones — with happiness imagined rather simplistically as a combination of health and comfort. The metaphysical society which had organized monotheism at its social and ethical heart is now a largely therapeutic and individualistic one, where ‘treatments’ are bought and sold but fail to deliver. Our lives have become increasingly self-centered, isolated and meaningless, and that makes us even more unhappy. Peterson sees these problems and addresses them head-on in 12 Rules for Life. But his solutions contribute to the general problem, for they are themselves another kind of ‘treatment’ or therapy, with order, meaning and myth presented as tools in the pursuit of well-being. The degree to which they are offered merely as tools acquired by reading a book or watching a few videos — not by joining a convent or selling everything and becoming a disciple — is the degree to which they are Spenglerian symptoms of Der Untergang des Abendlandes, the ‘decline of the West’.

If there will be any saviors of western civilization, and I doubt there will, they will be the nameless many — the ones without a platform or book contract who will get married and stay married, will raise and teach their children well, will help the weak and the poor, will love truth and live for their children’s futures rather than their own presents. T.S. Eliot discovered that rummaging among Christian and pagan fragments doesn’t take you very far. Peterson’s readers may yet come to learn this, too.

This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.