The World According to Joan Didion is an example of a regrettable new trend — the solipsistic biography. I mean lives of famous people written by unfamous people (usually women) who want to tell you a LOT about themselves. This one is about the writer Joan Didion by an academic called Evelyn McDonnell who never met Didion but believes that they had much in common. Here is her evidence. “She was born within one year of my mother; I was born within two years of her daughter. We are both native daughters of California. We lived in New York at the same time, though she was an Upper East Side celebrity and I was a Lower East Side punkette. We both wrote in order to live. We both thought about the sea whenever we felt troubled.”

Soul sisters, right? What McDonnell fails to have noticed is that Didion was a fastidious writer who would never describe herself and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, as “peers and equals” because she would avoid tautology. She didn’t waste words. She taught herself to type by copying out stories by Hemingway because she admired his style. McDonnell of course disapproves of Hemingway. In many ways she disapproves of Didion too because she voted for Barry Goldwater in l964 and wrote for National Review. Worse still, she was not a feminist. Didion admired strong men, like the actor John Wayne, and writers Norman Mailer and Hemingway. And she wrote a fierce article about the women’s movement in 1972 that accused it of “little sophistries, wish-fulfilment, self-loathing and bitter fantasies.” McConnell feels that Didion “needed some feminist consciousness-raising.”

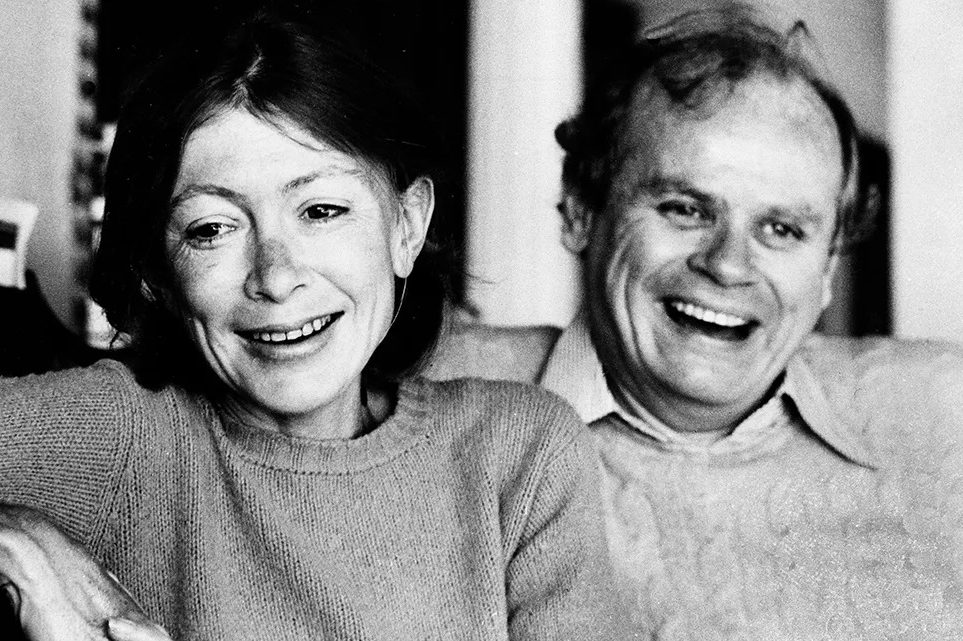

Luckily we don’t have to read McConnell when we can read Didion — we can track most of her life from her five novels and ten volumes of non-fiction. She was born in Sacramento in 1934, and was proud to be a fifth-generation Californian. She studied at Berkeley for four years, then won a Vogue writing competition and swapped her prize — two weeks in Paris — for a job at the magazine, and moved to New York. At first she was given only merchandising copy to write but soon progressed to film reviews and also wrote her first novel, Run River, about a murder on the banks of the Sacramento River. Then she married Dunne, a fellow writer, and moved with him to Los Angeles. He was one of a large gregarious Irish Catholic family (including the Vanity Fair writer Dominick Dunne), which Didion found attractive, but he had “a horrible temper.” The marriage was rocky at first — she remembered “chronic anxieties and packed suitcases” — but they stuck it out and, unable to have children (for reasons Didion never explained), adopted a baby daughter, Quintana Roo, in l966.

Didion said of herself in the introduction to her first collection of journalism, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968): “My only advantage as a reporter is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.” This was true: friends complained that she seldom talked. She also looked frail — only 5’1″ at her tallest, skeletally thin, possibly anorexic, subject to migraines and depression. She had a breakdown in 1968, suffering from vertigo and nausea, and was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis when she was thirty-three though it never developed. And in fact she lived to eighty-seven.

McDonnell claims to have spoken to people who knew Didion but it’s not clear what she gleaned from them

She and Dunne became a celebrated power couple in Hollywood, known as the Didion-Dunnes, writing three films together and acting as script doctors for many more, though she never took film writing very seriously. They lived lavishly, and dined out most evenings. Meanwhile, she worked hard at her journalism, covering topics as diverse as El Salvador, Miami and George Bush’s defeat by Bill Clinton. In 1988, they moved back to New York because Dunne was beginning to have heart problems.

On Christmas Day 2003 their daughter Quintana was hospitalized with a septic infection and went into a coma. The Didion-Dunnes visited her in the ICU every day but on the fifth day Dunne said: “I don’t think I’m up for this.” Didion told him curtly, “You don’t get a choice,” and carried on making dinner. Then he collapsed and died. Thus began her Year of Magical Thinking. She insisted on attending Dunne’s postmortem because she believed that if she could understand what killed him, the damage could be repaired and he would still be alive. Nor would she throw his shoes away because he would need shoes when he returned. Meanwhile she still had to keep visiting Quintana in hospital and, when she eventually emerged from her coma, had to break it to her that her father had died.

Nine months after Dunne’s death Didion started writing her most successful book, The Year of Magical Thinking, and finished it in three months. But Quintana died of pancreatitis while Didion was on her book tour and Didion wrote about her death in Blue Nights (2011). Didion went on writing during her long (eighteen-year) widowhood but eventually died of Parkinson’s in 2021.

Zadie Smith wrote a brilliant piece in the New Yorker about why she admired Didion. Reading Didion, she said, made her realize that “a woman could speak without hedging her bets, without hemming and hawing, without making nice, without poeticisms, without sounding pleasant or sweet, without deference, and even without doubt.” What she admired most was her “authority.”

If only McDonnell had learned these lessons. In her acknowledgements she claims to have talked to several people who knew Didion personally though it is not obvious from the text what she gleaned from them. She also thanks some of her students at Loyola Marymount University who helped with the research and did the fact-checking. More fulsomely she thanks “several girl groups [who] helped me get through the last few years and even decades… Susie Horgan is my sounding board for life. Laurie Steelink. my swim sister.” Finally she thanks her husband, Bud, for building her “a studio a writer can only dream about: a Gehry-esque wheelhouse perched on a hill with a panoramic view of the ocean.” Lucky old McDonnell. Unlucky Didion, getting such a poor biographer.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.