Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton; Alice Paul and Sojourner Truth; Ida B. Wells and Carrie Chapman Catt. They may not be household names, but to anyone with a passing interest in US women’s history, they’re hardly obscure.

They’re widely associated with America’s fight for women’s suffrage: a tribe of trailblazers who’ve made it into history books and onto overpriced tote bags. Some were popularized by the Tony Award-winning musical Suffs. Three are immortalized as statues in New York’s Central Park.

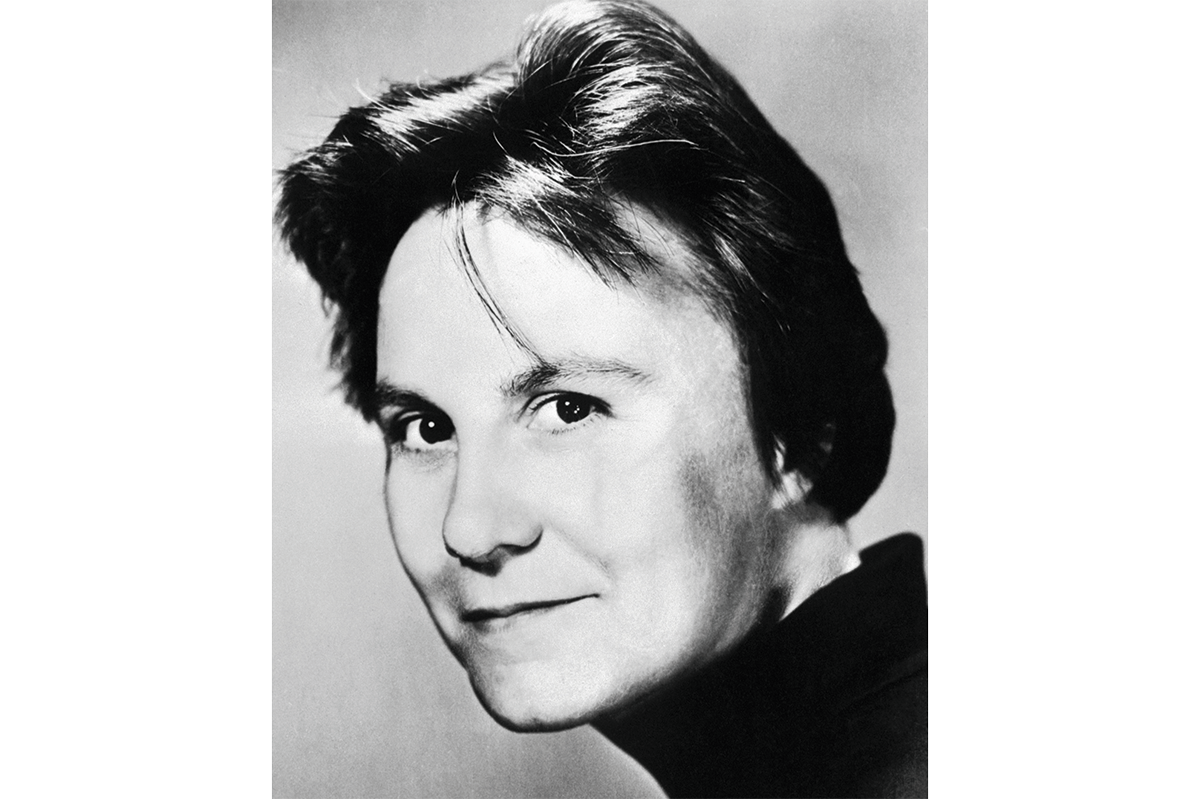

But behind the scenes of their various campaigns, another woman charted her own course for the same cause. Frequently crisscrossing the country, Jeannette Rankin, an unmarried Montana woman whose pacifism made her a pariah in wartime Washington, is not only one of the most overlooked figures of the suffrage era, but was also the first woman ever elected to the US House of Representatives.

In Winning the Earthquake, the first comprehensive biography of Rankin’s restless and radical life to appear in decades, Lorissa Rinehart tells the improbable story of how the daughter of a schoolteacher and a millowner, born in Missoula in 1880, reached the pinnacle of state politics by doing everything that women at the time simply didn’t. She studied hard and went to university. She traveled alone to the other side of the world, working in New Zealand as a seamstress so she could surreptitiously study social conditions. Later, she drove her banged-up Chevrolet – “like a bat out of hell” – from coast to coast, knocking on doors and mounting every soapbox as she went, demanding that America let women vote, abolish child labor, and end the carnage of senseless wars.

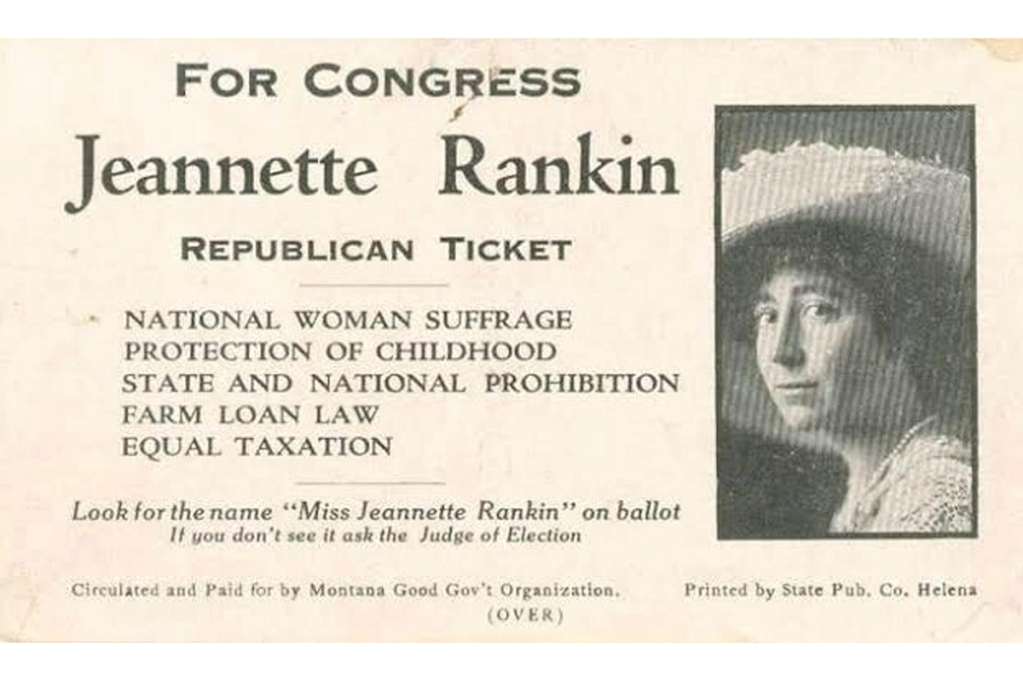

Four years before the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 which – theoretically at least – gave millions of American women the right to vote, Rankin secured that historic seat as a Republican in Congress. She was known, of course, for her sex, but not only that. In her run for office, she’d beaten out a Montana oligarch and prided herself on her grassroots approach to campaigning, appealing to the disenfranchised everyman. Casting herself as a woman of the people – a workers’ worker – she advocated for ranked-choice voting, multimember congressional districts, universal absentee balloting and the abolition of the Electoral College.

But to the Washington elite, it was something else that ultimately came to define her political career. Her first vote in Congress was against America’s involvement in World War One. It didn’t only cost her a seat at the pro-war suffragists’ table, it also attracted vitriol, ridicule and, unsurprisingly, plenty of rampant misogyny. When, during her second term in Congress, she voted against the country’s involvement in World War Two, one newspaper declared of Rankin: “She voted no, but as everyone knows, when a woman says no, she doesn’t mean it.”

For all the praise Rinehart offers Rankin – for her perseverance, her fight for civil rights, her role in reshaping the fabric of American society – she resists the temptation to lionize a figure who was undeniably flawed, complicated, socially awkward and frequently furious. Rinehart does not shy away from chronicling Rankin’s vicious outbursts, those “bouts of temper [that] often boiled into full-blown volcanoes of rage.” Nor does she gloss over the congresswoman’s more provocative exchanges with fellow politicians. Instead, she crafts a three-dimensional portrait of a woman seething with irritation and perpetually exasperated by the world around her.

In one memorable exchange, Rinehart writes, Rankin excoriated a congressman for being unwilling to utter the word “syphilis.” In another, she blamed the government for spending more money on the study of hog feed than on research into children’s wellbeing. She also writes about Rankin’s stubborn refusal to respect her physical limitations. For decades, she suffered from trigeminal neuralgia – known as tic douloureux, a chronic nerve disorder that can cause sudden, paralyzing facial pain.

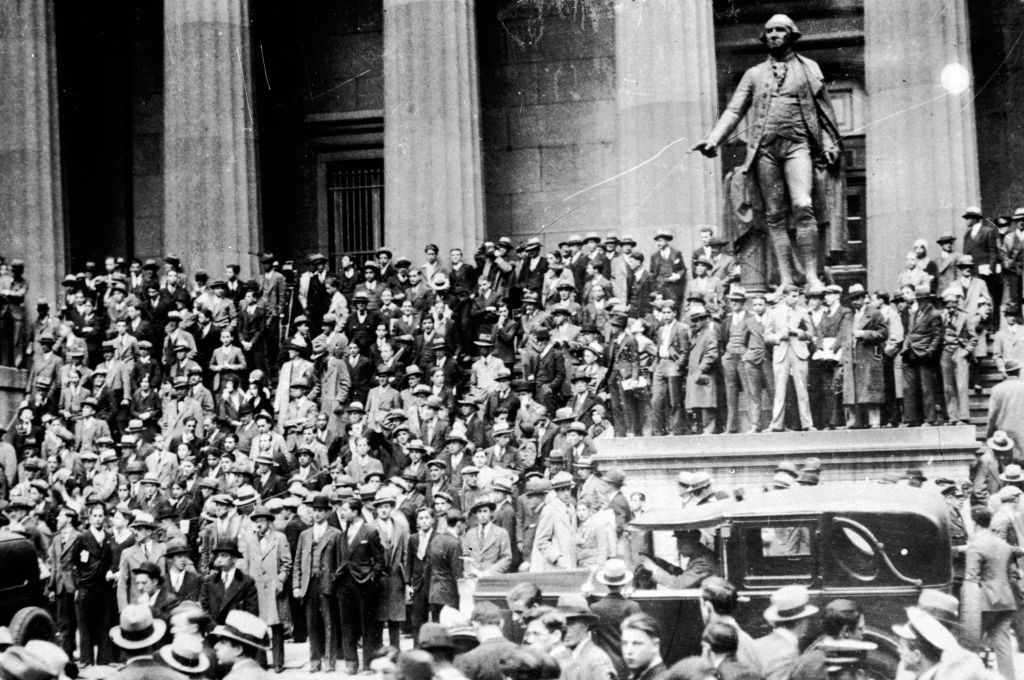

While Rinehart’s narrative is propelled by her accounts of Rankin’s soaring highs and crushing lows, it is enriched by vivid imagery that captures the drama. “The cataclysmic stock market avalanche continued its slide into the sea that summer,” Rinehart writes of the financial nosedive of 1929 and 1930, “unleashing a series of seismic waves that pounded the shores of Europe and pummeled its economic pillars.” Descriptions like this transform what could be a dry historical biography into an unlikely against-all-odds tale of power, tenacity and ambition.

What’s also impossible to ignore is the timing of Rinehart’s book. Rankin’s relevance to what’s happening today in the very place where she tried – and often failed – to wield power. Her calls for electoral reform, once dismissed as utopian and eccentric, reverberate in debates over ranked-choice voting and the legitimacy of the Electoral College. Her pacifism, ridiculed in her own time, feels different in an era in which the world’s on fire. And her insistence that women’s voices be heard in Congress remains undeniably urgent as reproductive rights are stripped away and women’s history is erased from school curricula.

In 1993, two decades after her death, Rankin was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame. A statue of her stands in the US Capitol, often unnoticed by those who stride past it every day. With this biography, Rinehart tries her utmost to rescue Rankin from obscurity – indeed, she insists on her place in the story of American democracy. And yet, Rankin may always remain a kind of footnote: a figure who never quite fit the neat arc of history, as written by those who very much conformed.

Her true power lay in her refusal to be like the others – like other Republicans, like the suffragists, like the industrialists, like the pro-war establishment. And Rinehart shows us that it might have been this very defiance that ensured her erasure.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply