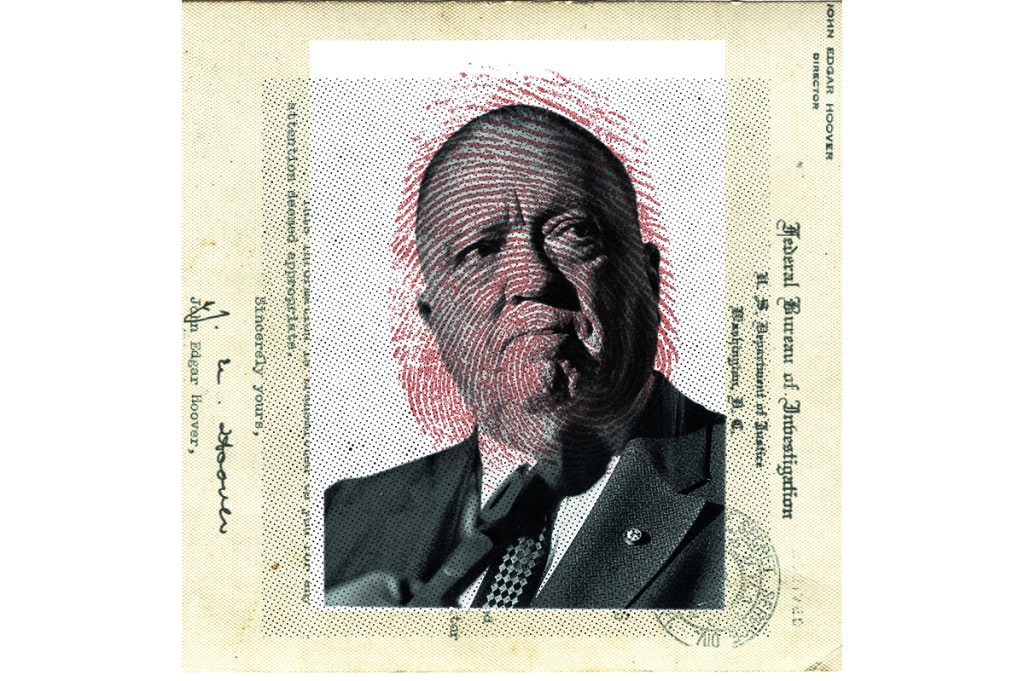

When J. Edgar Hoover died in May 1972 at seventy-seven, he had been director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation for forty-eight years, ever since progressive attorney general Harlan Fiske Stone had promoted the then-obscure twenty-nine-year-old Justice Department bureaucrat in 1924.

With fewer than 400 agents, limited responsibilities, and a reputation badly tarnished under a corrupt previous attorney general, what was then called the Bureau of Investigation offered modest prospects. Still, the new boss set out to clean house, institute stringent hiring standards and impose a culture of science-based crime-fighting on his federal agents. One new hire in 1928 was Clyde A. Tolson, five years younger than Hoover, who by 1931 had been named an assistant director and emerged as Hoover’s regular traveling companion.

For Hoover, the Bureau became his life. During the early 1930s, a wave of violent criminality forced Hoover’s men into an intense shooting war which transformed the FBI as Congress aggressively expanded federal criminal jurisdiction. Even more significantly, Hollywood celebrated this transformation, with films such as James Cagney’s 1935 G-Men making “the crime-fighting federal agent into a staple of popular culture,” as Yale historian Beverly Gage writes in her new biography of Hoover.

Thirty-five years have passed since the definitive Hoover biography, Richard Gid Powers’s Secrecy and Power, appeared in 1987. While the ensuing decades have let loose hundreds of thousands of pages of once-secret Bureau files that allow Gage to paint the richest political history to date of Hoover’s FBI, analytically and interpretively Gage does not diverge from the pathbreaking books of Powers and the late Athan Theoharis.

While the film industry quickly “made Hoover into a national legend,” even more important for the FBI than the 1930s “War on Crime” was the presidency of the man who coined that phrase, patrician liberal Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt. The 1930s also witnessed the growing popularity of both fascism and communism, in the United States as well as overseas, and Roosevelt insistently tasked Hoover with investigating those two domestic threats.

First in 1936, then again in 1938 and 1939, Roosevelt issued instructions for the Bureau to increase its domestic political surveillance, culminating with a May 1940 order authorizing telephone wiretapping, which Hoover previously had shunned. Roosevelt also directed Hoover to investigate the president’s own political critics. When Hoover complied, FDR gushed with praise: “You have done and are doing a wonderful job, and I want you to know of my gratification and appreciation.”

Hoover was still living with his widowed mother in his childhood home until she died in 1938, and only then, at forty-three, did he purchase a house of his own in leafy Northwest Washington. Five years later, during the midst of World War Two, a then little-known Texas congressman and his family moved in a few doors down. The Johnsons saw nothing untoward in Hoover’s close partnership with his deputy Clyde Tolson, yet Gage, in her only serious misstep in an otherwise perceptive book, follows in the footsteps of scurrilous journalists by insisting that the Hoover-Tolson relationship must have been a sexual one, even without any reliable firsthand evidence supporting such a view.

Years ago, both Powers and Theoharis conclusively rejected the “decades-old hearsay” that underlay such notions. Although Gage acknowledges that what was “most striking” about the Hoover-Tolson partnership was “its openness, vitality and broad social acceptance,” she fails to plumb why, in the 1930s, a prominent federal official who knew he was gay would insistently appear in public with his boyfriend. Gage instead contends that the two men manifested such an “erotic intimacy” that it was “obvious” that “sex” was part of their relationship, while conceding that “we know very little about Hoover’s innermost thoughts and feelings.” G-Man would have been a better book had Gage avoided such an entirely speculative stance.

While Hoover strongly opposed Roosevelt’s racist policy of mass internment of Japanese (yet not German or Italian) Americans, World War Two brought yet a second transformation of the Bureau as it pivoted toward pursuing German saboteurs and then Russian spies. That required “a shift in the Bureau’s culture” from “professional law enforcement” to “intelligence and counterespionage,” and by 1945 the Bureau had almost 5,000 agents, a more than ten-fold increase compared to twenty years earlier.

Roosevelt’s successor, Harry S. Truman, upped the ante on Roosevelt’s electronic surveillance stance, instructing Hoover to wiretap one of his own White House aides and reveling in the resulting transcripts. By the late 1940s, the Bureau was focusing its attention on the domestic communist threat, and Hoover’s own national popularity was sky-high. A series of Gallup polls between 1949 and 1953 found only a consistent 2 percent of Americans strongly disapproving of him, results Gallup said were “virtually without parallel in surveys that have dealt with men in public life.”

In the early 1950s, the Bureau scored a top-secret coup against the US Communist Party (CPUSA) by recruiting two of its most important longtime operatives, brothers Jack and Morris Childs, as well-connected informants. Not only could the brothers attest firsthand to the transfer of Soviet funds to the US party, within several years Morris was traveling to Moscow, and then to other communist capitals such as Beijing and Havana, as the CPUSA’s international representative — all the time briefing Hoover’s agents about what he learned. “SOLO,” as the brothers were code-named, became arguably the most influential operation in FBI history, yet Hoover’s own long-standing anti-communist proclivities made him all too eager to accept the Childs brothers’ detailed reports of CPUSA leaders’ boasting about the importance of their members’ secret friends. As Gage writes, “at no point did Hoover seem to entertain the idea that communist leaders might be exaggerating their own influence.”

Hoover’s preoccupation with the CPUSA led him to undertake an aggressive initiative actively targeting top party members, one whose name would eventually live in infamy: Cointelpro, for “counterintelligence program.” Hoover entered the 1960s celebrated as the nation’s greatest living public servant, but over the course of the decade, as Cointelpro expanded beyond CPUSA to target “White Hate Groups” such as the KKK, “Black National Hate Groups” ranging from the Nation of Islam to the Black Panthers and the young, white “New Left,” Hoover “departed more and more from his vision of the FBI as a professional, apolitical institution,” Gage asserts.

The first Cointelpro was implicitly blessed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and a succession of congressional leaders, but when the FBI tardily realized that one of the SOLO brothers’ old CPUSA compatriots from the early 1950s, New York businessman Stanley Levison, had become Martin Luther King, Jr.’s most influential advisor, Hoover’s conviction that the CPUSA’s tentacles were far-reaching morphed into his over-the-top targeting of King himself.

Gage does a superb job of narrating in rich detail the entire tragic saga of the FBI’s pursuit of King, one fueled by extensive wiretapping that was authorized in writing by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy with the support of his presidential brother, and then hotel bedroom “bugs” too. Gage appreciates too how the FBI’s 1964 mailing of an anonymous package to King, intimating that he had best commit suicide to save himself from public exposure of his libidinous private life, was known to Hoover and not just the action of a renegade subordinate.

In 1963, Hoover’s old neighbor Lyndon B. Johnson was suddenly elevated to the presidency following John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Thus began a second hand-in-glove political collaboration, and his friendship with Johnson allowed Hoover to escape the mandatory retirement that should have taken place when he reached age seventy in 1965.

Paul Letersky’s The Director was published in mid-2021, apparently too late for G-Man to incorporate its signal historical importance. Letersky arrived at FBI headquarters in 1965 as a twenty-two-year-old clerk before being promoted, just a year later, to work directly under Helen Gandy, Hoover’s longtime private secretary, in the director’s personal office. Letersky’s memoir makes clear how the FBI’s actual number-two official was not the wizened Tolson — in two years, “I never once heard Tolson’s voice,” Letersky comments — but “Miss Gandy,” who, like Hoover, had “never married, never had children, never had a life outside the FBI” and was now the Justice Department’s highest-paid female employee and the gatekeeper through whom all other FBI executives had to pass to see Hoover.

Hoover’s rigid formalism dominated the office. “Control and supervision! That is the bedrock principle of this organization,” the director lectured Letersky upon first introduction. Gandy treated Letersky warmly, like an adopted son, even confessing, “Paul, I’ve worked for him for forty-eight years, and not once has he ever called me Helen.”

To Letersky, Hoover was “the most seemingly unemotional man I’d ever met,” and like all FBI veterans who personally knew the “rigidly” self-controlled director, he too dismisses the notion that Hoover was gay. He “might have been asexual,” or “perhaps he was physically dysfunctional sexually.” Only once did Letersky hear Hoover express strong emotion, and that came on the evening of April 4, 1968, when Letersky called the director at home to inform him that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot in Memphis. “I hope the son of a bitch doesn’t die. If he does, they’ll make a martyr out of him.”

Just as Letersky was leaving Hoover’s office to train as an actual agent, the Bureau’s number four official, J.P. Mohr, warned Letersky of one thing to avoid: “if this Cointelpro stuff ever gets out, it’s going to blow up in our faces.” Three years later, when a small band of Philadelphia academics broke into the small FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, to liberate its files and surreptitiously share them with journalists, only one insignificant document bore the label “Cointelpro,” and by the time its meaning became clear, Hoover was dead. At his funeral in 1972, Letersky sat with Tolson on his right and Gandy on his left.

As Gage writes, Hoover “died just in time to avoid witnessing the public repudiation of his life’s work and the destruction of his reputation.” He had “exerted unparalleled influence over American politics and society for more than half a century,” but in death Hoover “ended up as the nation’s greatest political villain,” notwithstanding how for decades millions of people, from presidents downward, “had always aided and supported him . . . because of his willingness to target those who challenged the status quo.” Such has been his unique, twisted legacy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.