Apart from Bob Dylan and Kazuo Ishiguro, it’s a fair bet that most people’s reaction to the Nobel prizewinners for literature this century is, who? Arguably the most recent, Jon Fosse, is an exception but the majority of winners don’t really stand up to the weight of the award. Annie Emaux? Abdulrazak Gurnah? Louise Gluck? It’s hard to avoid the impression that the judges were swayed by ethno-gender considerations rather than outright lifetime literary merit.

I asked him about Albania obtaining European Union membership and he got tetchy

This week there died, and today was buried, one man who really did merit the award for which he was nominated fifteen times, and really did want it and who never got it: Ismail Kadare. The eighty-eight-year-old may be unknown to most, but that says more about the insularity of literary culture than his merits. He was the real deal, a novelist who created something unique; a kind of allegorical symbolism which cut through time to say something about the eternal truths of despotism and liberty in telling a story about a different period and place. Kadare was indisputably Albanian, indisputably a national writer, but like all great writers he was both rooted in a particular place and universally comprehensible.

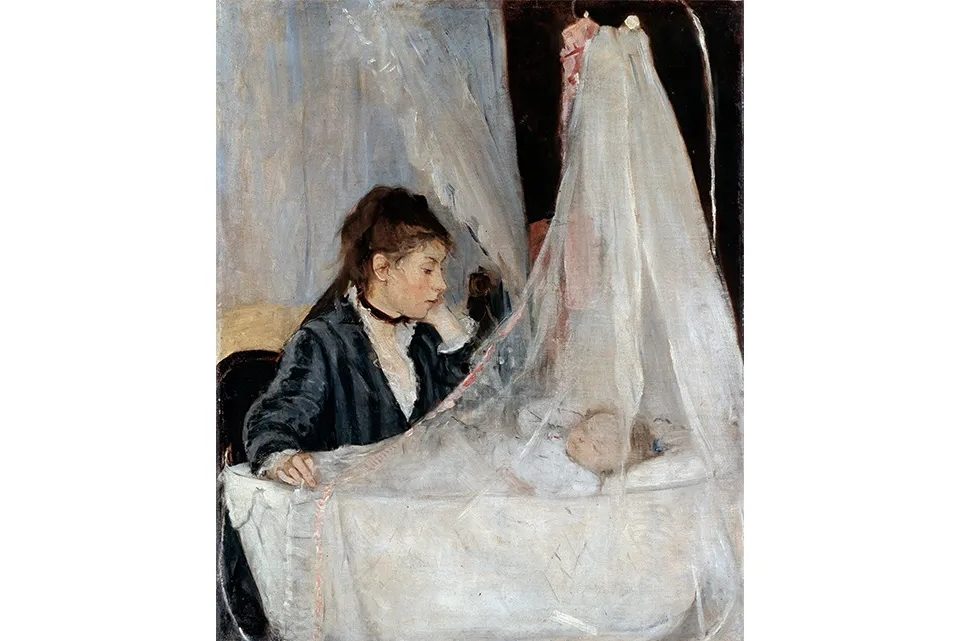

The General of the Dead Army, his breakthrough novel, was about an Italian general scouring Albania for the bones of the Italian soldiers who died there during the Italian occupation and was about all war as well as that war. Somehow, the spirit of his home town Gjirokaster, permeates many of his narratives. The Three Arched Bridge was the chronicle of a fourteenth-century monk who documented the doomed attempt to build a bridge across a stretch of river called the Wicked Waters which will destroy the old boats and rafts system; a metaphor for the modern Balkans as well as the old. The Palace of Dreams is a haunting story about a boy whose job in the Ottoman bureaucracy is to interpret the dreams of the Sultan’s subjects, but there are some dreams that are threatening to the stability of the state, and are dangerous. The metaphor is obvious, but never, I find, heavy handed. Shades of Kafka? I think so.

Kadare spent time in Moscow before the break between the Soviets and Albania and that too fed into his work. The last book was The Doll, an account of the life of his mother, and a more realistic depiction of that generation of Albanian women than most readers found comfortable.

Kadare was criticized for being what he was not, a dissident political writer. He sought asylum in France after the death of the dictator Enver Hoxha on the basis that his life was in danger from the regime that followed, and that assertion seems perfectly plausible. Yet, under Hoxha, he wrote under the radar and in metaphor rather than in direct criticism of the regime; given the terrifying nature of that dictatorship, it strikes me as a sensible course.

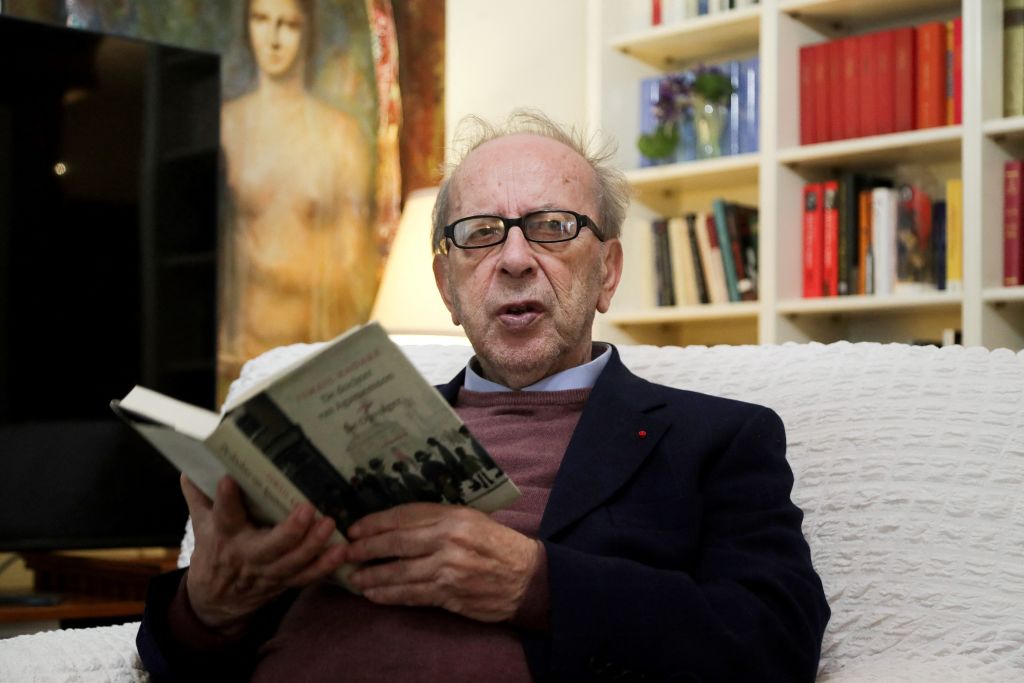

I met him a few years ago in Paris where the French state, having a genuine regard for culture, had given this literary exile and his wife a lovely flat near the Boulevard St. Michel. He was hospitable and accessible. There were a few things that struck me in the course of our conversation. He had lived in the very same street in Gjirokaster in which Enver Hoxha had grown up. When I asked him when it occurred to him that Hoxha was going to be very bad news, he said simply that his grandmother didn’t have any time for the Hoxhas. “Not a good family,” she said dismissively. And so it turned out.

Kadare was more open in his views of the dictator outside Albania than inside it, but he recalled that when he met Enver’s widow, Nexhmije Hoxha, the Elena Ceaușescu of Albania, in Paris, she said to him, “You were not honest with us.” He showed her his ankle. “Would you, he said, be honest with a snake?” In other words, would you say what you thought if it meant being struck down?

I asked him about Albania obtaining European Union membership and he got tetchy. “Albania is in Europe,” he said flatly; unconsciously channeling the Brexit view that Europe doesn’t mean the EU. He disliked Islam and was especially hostile to the Turkish influence in the Balkans, contemporary and historic. Remember, Ottomanism is not an antiquarian question these days; it’s the preoccupation of the Turkish president Erdoğan, who quite fancies Turkey as a reincarnation of the Ottoman Empire, complete with Islamic expansionism.

What he said in an interview elsewhere is worth us taking to heart: “I have created a body of literary work during the time of two diametrically opposed political systems: a tyranny that lasted for thirty-five years and twenty years of liberty. In both cases, the thing that could destroy literature is the same: self-censorship.” That has resonance, no?

Kadare was a sound man and his works will live on. So more fool the Nobel prize judges for passing over, year after year, the one European writer who really deserved the prize. He did want it, and laughed amiably when I said it might come next year. I was wrong.

If Kadare deserved the Nobel prize, his English translator, John Hodgson, deserves a prize of his own for his brilliance in rendering Kadare so accessible to English speakers; in French his equivalent was Jusuf Vrioni. The translator is the glass through which an author shines in another language; if it’s done well, you don’t notice it; if it’s badly done, you do. His translations were wonderful.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply