Is The Idol a stunning piece of trash, or a trashy masterpiece? Whatever the answer, the HBO show, debuting Sunday, is sure to make an impression.

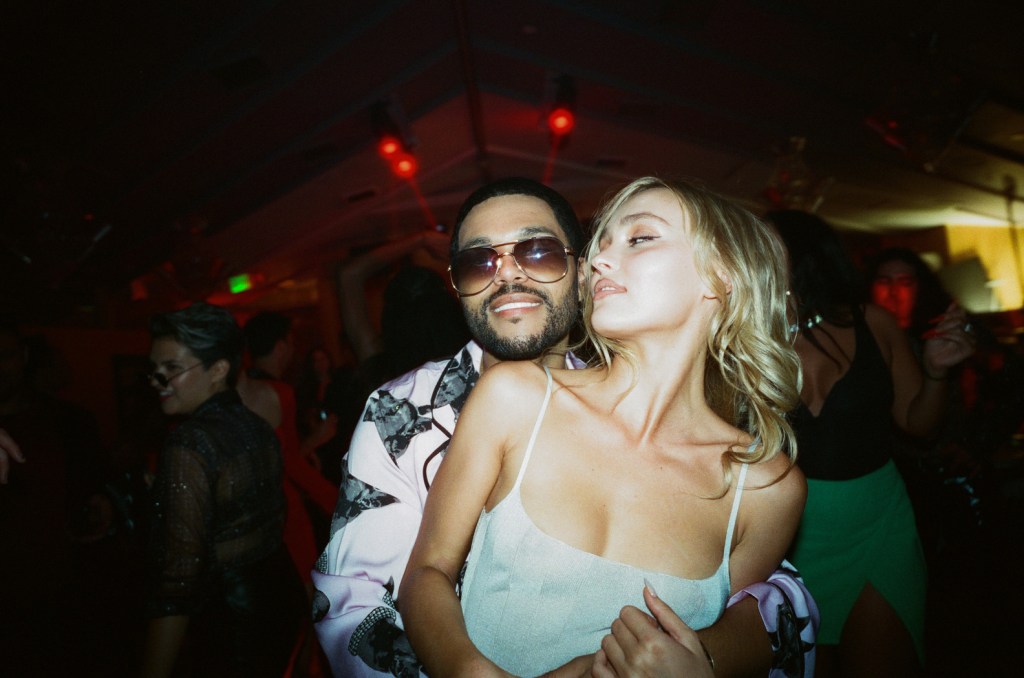

It’s set to be 2023’s Spring Breakers; a lurid spectacle of Hollywood by blacklight, as Lily-Rose Depp’s Britney-inspired pop vamp Jocelyn falls for a manipulative cult leader, played by musician The Weeknd. And critics hate it. They cry it’s “toxic,” “grim, gross and vulgar,” “degrading and hollow.”

The Idol is the latest show from Euphoria’s Sam Levinson, and fills the prestige 9 p.m. slot previously occupied by the high-brow Murdoch satire Succession. Succession was subtle, witty and emotionally rich, and became a perennial obsession of the writerly class. Its finale has a 100 percent score on Rotten Tomatoes, and was written about in a thousand op-eds, praising it (rightly so) as a brilliant piece of almost Shakespearian, literary television. Levinson offers something very different.

He’s a smut-peddler of the finest kind; a visual genius obsessed with creating incredible, dramatic images and making them pop as much as possible. He doesn’t care for rich characters that subtly reflect on the state of American men, and elegant narrative conclusions. He loves tits and drugs, money and glamour, ditsy blondes and psychopathic, homoerotic jocks. Everyone’s hot and always shirtless. It’s about the vibe, not the plot. His dialogue isn’t witty or realistic, but camp. Looking at leaked photographs of their town’s mayor, one of the teen leads of his 2018 film, Assassination Naton, cries “Oh fuck, why do middle-aged men who cross-dress always have the worst taste in lingerie?”

His aesthetic is bold: neon lights, billowing fog machines and grainy 35mm film; synthy electro-pop score and acerbic over-the-top narration; bright, flamboyant costumes, and dramatic, expensive sets; and sex. He loves shooting sex. Sweet, romantic sex; violent, disturbing sex; masturbation, asphyxiation, gay sex, straight sex; as long as they’re screwing, he’s shooting. His work is funny, horrifying and sexy, often all at once.

It’s smut; but it’s the world’s most beautiful, artfully shot smut. And smut is underrated.

Though much criticism aspires to some standard of objective assessment — considering work as part of a broader cannon, relating to previous texts, the effective use of established tools and creation of new ones, and so forth — it often isn’t, particularly when art gets extreme. De Palma has never been as appreciated as Hitchcock, even when his films were better. The pornography of Vixen Studios is visually masterful, and of enormous significance to the field, but you’ll never read a review of it in the Times, and there are few great porn critics.

Most galling is the lack of respect given to the “French New Extreme” movement of the 2000s, where French filmmakers used gore and extreme violence as tools for telling deep, rich stories. Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs is a cinematic masterpiece. It deserves its place among the greatest horror films ever made — neigh, greatest films ever made. And yet, because it is so uncomfortable to watch, few critics gave it its shine. It was brushed away with David Edelstein’s dismissive, “torture porn.” He coined the term in a 2006 piece that ends complaining about Gaspar Noe; one of the great filmmakers of our era.

I will note that Edelstein ended his Captain Marvel review with the following:

At full strength, her Captain Marvel is a goddess emitting her own light — an astral version of Liberty at the battlements, sublime and terrifying. In my favorite moment, she returns from outer space, loses the cosmic luminescence and gives a little smirk that suggests, “Aren’t I Marvel-ous?”

Captain Marvel is not artful. It’s cringe-filled corporate gruel, made for selling merchandise to infants and the infantile of mind. The only feeling it provokes is a kind of existential dread, that our species invented the greatest medium for story telling ever, and used it to produce this.

But just six months earlier, I’d left the cinema grinning widely, having just seen Levinson’s Assassination Nation. Both the greatest and worst adaption of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, it’s tasteless, splashy, comic delight, opening with sardonic “trigger warnings” — with “TORTURE,” “GORE,” “TRANSPHOBIA,” “RACISM” and “SWEARING” plastered across the screen in red, white and blue — and ends with a black marching band playing Miley Cyrus’s We Can’t Stop. You want introspective reflections on the great divide in American society and how partisan culture drives social tensions to the point of violent instability and the collapse in institutional trust? Pick up a book. Levinson knows he’s not an academic or intellectual, and though his political themes are as understated as his aesthetic, he’s winking with them too. If you’re annoyed when an incensed Salem mob starts shouting “Lock Him Up,” you’ve missed the point. It’s just about the vibe.

Levinson’s masterpiece would release the next year; Euphoria, an adaptation of a 2012 Israeli miniseries of the same name. In both shows, a group of broken teens plug their psychological and emotional holes with drugs, sex, and violence, and gradually spiral out of control. The difference is the look. Ron Leshem’s original has the muted, hand-held, soft-focus style found among an endless number of DSLR-shot indies. But Levinson’s Euphoria is a spectacle. Find me another teen drama pilot with dolly zooms, snap pans, undercranked cameras and dramatic match cuts. And what is this gorgeous filmmaking used for?

Smut, sir. Pure, uncut, brilliant smut.

Having opened with a baby resisting leaving its mother’s womb, Levinson hard-cut to shots of 9/11 and narrates this whole sequence with the pessimistic monologue of Zendaya’s constantly-relapsing Rue. The episode will go onto to show a chain-wearing child drug dealer; a teen trans girl flicking through the erect phalluses sent to her from grown men on a dating app; a topless teen asking her friend whether her areolas look weird; and then our main character providing a detailed explanation of how to pass a drug test, by sourcing urine from a clean friend. Welcome to suburbia. This is all in the first half of the pilot, and the show never loses its edge. In the first season’s sublime carnival episode — which opens with a dramatic faux-“oner,” as the omniscient crane-held camera weaves through the enormous set — Sydney Sweeney’s Cassie takes ecstasy, and as she rides a carousel, loudly climaxes from the vibrations. It’s is an absurd, trashy, comic moment; but also emotionally raw for this character we care about, who’s still trying to assert and find who she is and wants to be.

Is the show a conservative condemnation of how the online pornography and Hefner’s vision of easy hedonism has corrupted adolescent sexual development and degrades teen girls? Is it an exaggerated portrayal of the collapse of mid-century American expectations, and failure of modern parents to adapt to the internet? Or does Levinson just like shooting this? It’s never quite clear.

Euphoria hasn’t ended — a third season is in the works, with a reported budget of $110 million — but The Idol is his next big gambit; even more vulgar, sexy, stylish and wild than anything he’s made before.

And people don’t like that.

In March, Rolling Stone released a large piece detailing the troubled production of the show, in which Levinson reshot almost all of it after director Amy Seimetz left. He changed its angle from “feminist escape” to “twisted love story’ which, according to Rolling Stone, “some crew members describe as being offensive.”

Troubled productions aren’t rare. In recent years, the chatter around Tinsel Town was how Noah Baumbach’s instantly forgotten White Noise was an expensive slow-motion shitshow to produce. But Baumbach — a polite, classy indie-darling — is admired and respected, and his tepid film was an adaptation of a high-minded piece of late twentieth-century fiction that many a high-minded journalist and media executive have bought for their bookshelf. You shouldn’t be surprised there wasn’t a single article written on the topic.

By contrast, The Idol is the perfect fodder for angry sources reaching out to Rolling Stone. It’s bold and vulgar, made by a “nepo baby” (Sam is the son of the acclaimed director Barry Levinson) and it’s about Hollywood. It even has a stand-in for Lynn Hirschberg. Worse of all, it’s also bound to be a hit. Succession’s finale only had 2.9 million viewers; season two of Euphoria averaged 16.3 million viewers, making it the second-most-watched HBO show ever.

The Idol promises everything Euphoria offers, and more. It has a great cast, incredible cinematography (courtesy of Arseni Khachaturan) and a lot of balls. It’s sleaze at its most offensive, glorious, glamorous best.

But we don’t want that! We don’t want to be offended! Wouldn’t it be just nicer to have more “cosmic luminescence” from Captain Marvel? I’m so excited for its upcoming sequel, The Marvels!!!

You’re not going to read fawning weekly breakdowns of The Idol in the New York Times. Critics will be too busy tut-tutting, watching the show with one hand covering their eyes, and the other otherwise occupied.