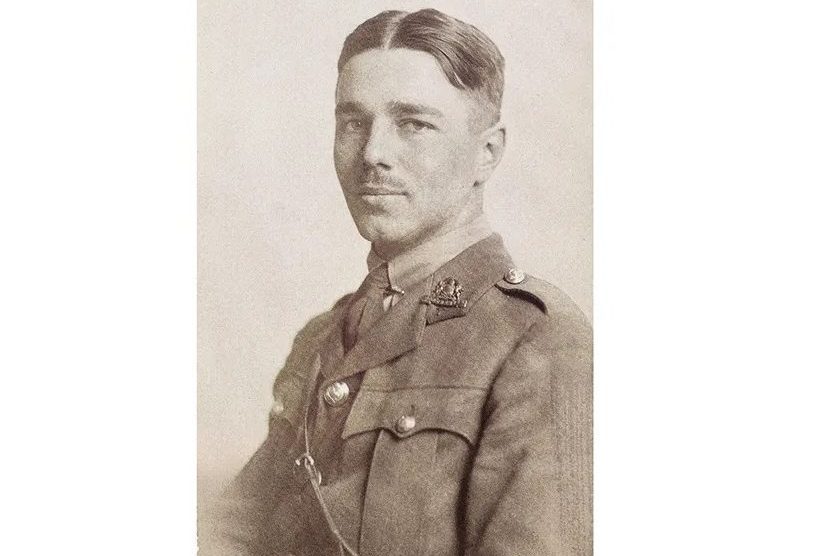

Here is the opening of a sonnet written by Wilfred Owen in the spring of 1911: “Three colors have I known the Deep to wear;/ ’Tis well today that Purple grandeurs gloom.” Owen was eighteen and had just been on a pilgrimage to Teignmouth in England, where his hero John Keats had once stayed. The kindest thing to say about this poem is that it is heavy with the influence of Keats. Six years later, in a seaside hotel requisitioned by the army and waiting to be sent back to the Western Front, he begins a poem like this: “Sit on the bed. I’m blind, and three parts shell.” This looks so simple. The monosyllables carry the meter without fuss; “shell” here means both munitions and protection. What happened to Owen between 1911 and 1917 — what turned the young Keatsian knock-off into the dazzling poet we still study today — is the story told in a new edition of his letters.

In January 1917 Owen is in a dug-out in no-man’s-land, trapped for fifty hours in rising water

In her preface to Selected Letters of Wilfred Owen Jane Potter writes that “Owen’s letters constitute his autobiography,” and she notes his surprising sense of humor and ability to evoke place and characters. This is only partly correct, and the background to these letters is far odder than first appears. They were initially published in 1967 in an edition co-edited by Owen’s brother Harold, who confessed in his preface that he had taken the decision years earlier to censor the letters by painting over them in thick lines of India ink, and now he couldn’t work out what he had crossed out. “The intention was to remove trivial passages of domestic news,” he claimed, but this wasn’t convincing even at the time. Of the 673 letters in this collected volume, 554 are to Owen’s mother. If this is his autobiography, it is centrally about his family relationships.

The other challenge of the letters is that a great many of them are fabulously dull. The young Owen had nothing to say, and said it again and again to his mother. “Yesterday we had beautiful weather, the sun was out nearly all day,” the fifteen-year-old reported. “On Wednesday, the vicar took me to a Bible Society Meeting at Henley.” It is horrible to admit, but reading letters like these makes one long for the trenches of the Somme.

In 1985, John Bell edited the Selected Letters, and Potter follows this in her own new edition: each of these selections sensibly cuts the majority of Owen’s teenage letters. Potter’s edition also follows the editorial practices, numbering and footnotes established by Harold Owen and Bell.

Owen was born in 1893, worked as lay assistant to a vicar near Reading and in 1913 moved to France as an English tutor. He was there when war broke out. In September 1914 he visited a temporary field hospital established in a school classroom. “Now a chamber of horrors where the ink was,” he wrote to his brother. “Germans being treated without the slightest distinction from the French: one scarcely knew which was which.” Owen’s real poetry begins here, with the key insight that in war the soldiers are victims.

Nineteen seventeen made him. Owen enlisted in 1915 and spent most of the following year in training. On New Year’s Day 1917, from France, he wrote to his mother: “I don’t think it’s the real front I’m going to.” Two weeks later he is in a dug-out in no-man’s-land with twenty-five other men, trapped for fifty hours in rising water. A few days after that he is gassed. He falls into a hole, bangs his head and is diagnosed with neurasthenia, or shell shock. He is sent to Craiglockhart hospital near Edinburgh to recover, where he meets the poet Siegfried Sassoon. Their time in the hospital has been brilliantly described by Pat Barker in her novel Regeneration. Here, Owen is writing, quickly, the poems which will later make him famous. On December 31, 1917 he writes: “I go out of this year a Poet, my dear Mother.”

His most famous poem is “Dulce et Decorum Est.” It describes a gas attack on a group of retreating soldiers, and the speaker watches through the “misty panes” of his gas mask as another soldier struggles and fails to put his mask on in time. It is a curiously distanced evocation. The gas falls behind them; the soldiers are, in a haunting metaphor, “As under a green sea;” and all of this is then remembered in a dream. This most celebrated of war poems is scarcely about warfare at all.

Owen’s letters — written to his mother, censored by his brother — are childlike and often banal, but ultimately they are a deeply moving supplement to his poems. Together, they insist upon a distinctively modern lesson: that the real story of war is not about weapons or strategy but lies in human transformation and victimhood.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply