In 1966, when Harry Harrison penned his dystopian thriller Make Room! Make Room!, which began life as a serial in Impulse magazine, he predicted that by 1999, there would be more than 7 billion people on earth, and a robust 35 million in New York City alone. The 1973 film adaptation of Harrison’s novel, Soylent Green, altered several aspects of Harrison’s novel, including the year in which the thriller is set: 2022.

Now that we’re there (and decades past 1999), it’s worth asking: did Soylent Green director Richard Fleischer and his writer, Stanley R. Greenberg, get things right? When Harrison penned his serial, inspired in part by the Malthusian hysteria of the ecological movement, the world population was just over 3 billion, with the five boroughs of New York City checking in at 15 million. In 1999, those numbers were 6 billion and 17.5 million respectively. Today, we’ve passed Harrison’s prediction of 7 billion worldwide, but New York City, at 19 million, is still less than half the 40 million that the film foresaw for our current year.

Fleischer, whose list of credits includes 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Doctor Doolittle (1967), Mandingo (1975) and Conan the Destroyer (1984), does a journeyman’s job of establishing the apocalyptic future at hand, giving us a sprightly montage of newsreel footage that rifles through cresting heaps of trash, showing cars locked in traffic jams as far as the eye can see, industrial waste belched upwards into the darkening sky and spewed out into debris-choked streams. It’s climate-change-on-crack, if you will. Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!

Gone are the posh, coddled streets of Manhattan; now we find an impromptu tent city, with people living in rusted-out husks of abandoned automobiles. To get to his brownstone walk-up apartment, our protagonist, NYPD detective Robert Thorn (played by Charlton Heston), must navigate a writhing throng of homeless sleeping in the stairwell.

At the top of those stairs there’s an armed guard to ensure none of the downtrodden gets too far up. It’s a metaphor for the society he lives in — get it?

As a comfortably employed member of the establishment (unemployment in the city is over 50 percent), you’d think Thorn might have decent digs. As is, he shares a cramped half-flat with an amiable old codger named Sol Roth (played by Edward G. Robinson, who died before the film was released), a retired academic and police investigator who every now and then hops on a stationary bike to power their humble TV.

In this austere future, the truly elite live well in modernistic luxe domes, fenced off and tucked away from the hordes. Such grand enclaves come with bodyguards, a house manager and what’s referred to as “furniture,” i.e. one or more young women assigned to provide service and pleasure. When one such upper-cruster is murdered (the mystery Thorn is investigating) and the abode sold, the “furniture” (Leigh Taylor-Young) becomes part of the asset transfer.

Clearly, neither Make Room! Make Room! nor Soylent Green anticipated the dramatic upheavals in gender relations of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, brought about by feminism in general and the #MeToo awakening most recently. But they were pretty spot-on in forecasting the widening wealth gap and expanding corporate influence (the Soylent Corp., the all-powerful provider of foods and services, is eerily akin to Amazon today), and the dystopic subjugation of women seems like further biting commentary against a society run by the strong and wealthy few.

Some things are comically dated, such as the film’s accents, its sense of future fashion and its rendering of the modern police force. As a law enforcement official, Thorn is hard to take seriously, garbed in a rumpled pastel cap and matching neckerchief and a cheesy Members Only jacket. The getup looks like Bogie’s skipper outfit in The African Queen, updated for the Eighties nightclub. Cops wear lacrosse helmets as riot gear, and their crowd-control vehicles are essentially garbage trucks equipped with a scoop to pick up and toss the disobedient starving masses into their cavernous bins.

Make Room! Make Room! and Soylent Green also whiff in the technological sphere. There is no evidence in either book or movie of the stunning advances we’ve really made in computers, the internet, AI and social media. That said, both the novel and the film keenly foresee our current agitation over the control and diffusion of information and misinformation. Whereas we have “fake news” and troll farms, the 2022 of Soylent Green plays out a Fahrenheit 451-style future, showing how the ruling class, through the abandonment of paper and literature, pretty much holds the masses in an uninformed, complacent stasis. Not too far off, really, from the ignorant distraction provided by the digital cosmos of today.

Back to that mysterious food company. Because the cataclysmic side effects of global warming have essentially left the land and the seas barren, the Soylent Corporation — whose flagship product is an amalgam of “soy” and “lentil” — has become the de facto food provider to the world. Beef still exists, but only as a super-scarce black-market luxury item. A jar of strawberry jam costs $150. What folks feast on instead are “Soylent Yellow” and “Soylent Red,” high-energy vegetable concentrates that come in wafer form. The corporation releases the new “Soylent Green” version, which a television pundit informs us is sourced from plankton.

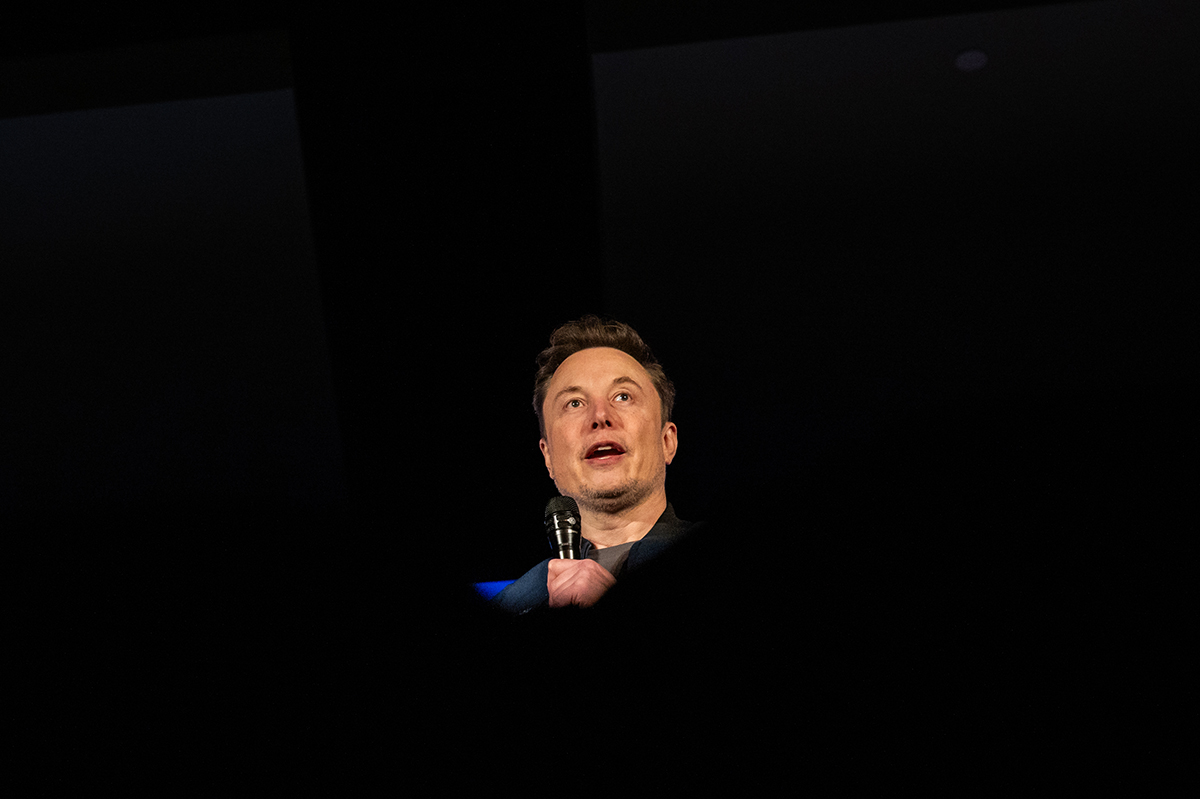

Today, back in the real world, we have lab-engineered plant-based “meat substitutes” like “Beyond” and “Impossible” meats, which cost about as much as their beef or pork analogues. There’s even a company called Soylent, founded in 2012 by overworked Silicon Valley workers looking for a quick, nutritious meal to get them through their high-tech grind. The company, named as an homage to Harrison’s novel, produces 400-calorie plant-based power-drinks that provide the nutrients of a complete meal. There are myriad flavors — vanilla, banana, chocolate and so on — to choose from. A twelve-pack delivered to your door will cost you just north of $40.

The narrative twist introduced by the film — spoiler alert — concerns the source of that titular sustenance, Soylent Green. Surprise: it’s not plankton after all (as it really was in the book), but human remains. The public is unaware of this unpalatable truth until the final frames of the movie, when a wounded Thorn, captured by the establishment, shouts out that indelible line to the teeming crowd around him: “Soylent Green is people!” It’s a sharp, demonic twist: the conundrum of overpopulation and decimated food sources is solved by clandestine cannibalism.

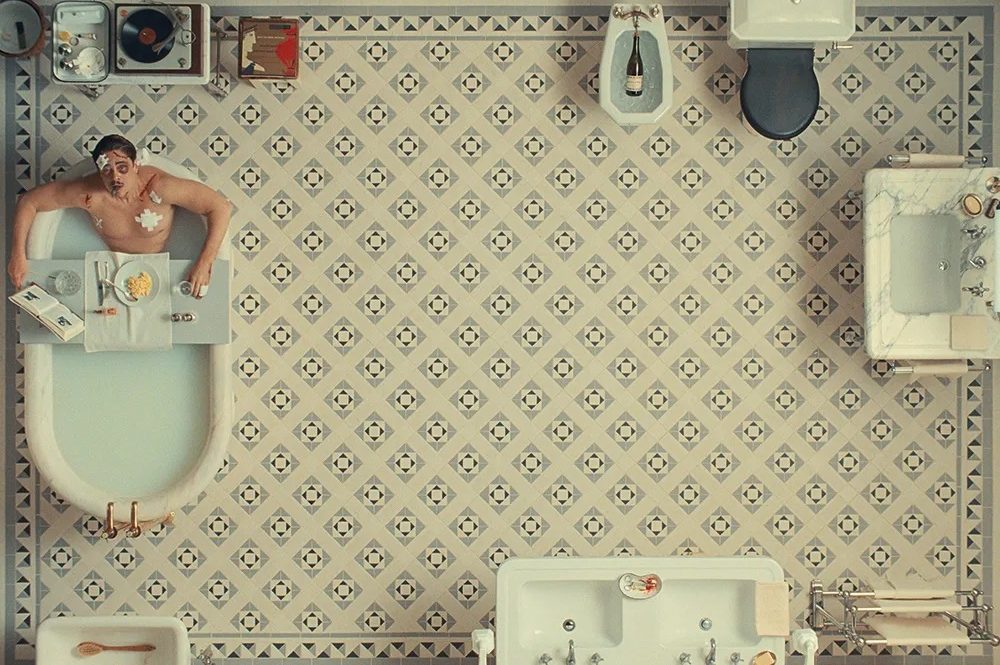

The government mandates the “retirement” of seniors through a spa-like process, where the to-be-euthanized get to choose their favorite color (in the case of Sol, orange), music (classical), and visual surroundings (a medley of fields, streams and fauna that no longer exist) for their tranquil fade-out. I’d liken it to going under for surgery, or that brief and pleasantly groggy state after a full-body massage. It seems like a relatively easy way to go, for those who must, though with the unseemly risk of grandson chowing down on grandpa when Tuesday’s portions are meted out.

While we’re not quite living out the fullness of Fleischer’s grim forecast for year 2022, red lights are flashing. The race for clean energy, reduced carbon emissions and sustainable food has been slow out of the gate. Yes, there are still fish in the sea, and deer still frolic in bucolic glens. But whereas in the Nixon-era 1970s, the dark, self-invoked damnation of Soylent Green felt like something from the pages of H.G. Wells — fantastical, and generations off — today one can envision the film’s desolate rendering over the not-too-distant hills uncomfortably clearly.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2022 World edition.