1922 saw its fair share of shocks in the literary world, among them the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. But perhaps the strangest book-related event of the year didn’t involve any writing at all, at least not as performed by human agency. Instead, the author was a ghost.

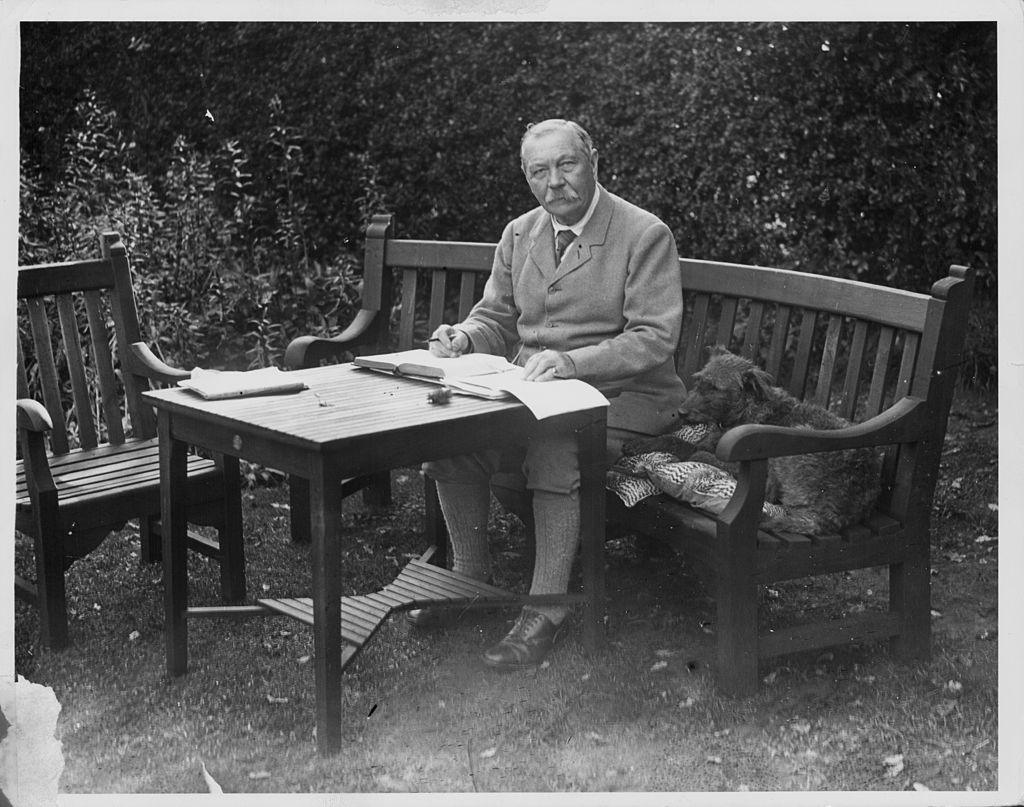

The setting was a darkened room at the Ambassador Hotel in New Jersey’s Atlantic City, where on the warm Sunday afternoon of June 18, 1922, Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame sat down between his wife Jean and the celebrated escapologist Harry Houdini to hold a séance. The first two of these individuals were advocates of spiritualism, the last of them a skeptic. Even the occult can have produced no stranger sight than that of the stout, 63-year-old author-lecturer, the creator of English literature’s most coldly rational detective, and the diminutive, 48-year-old magician — then arguably the two most famous public performers in the world — sitting with their heads bowed over the baize-topped table. They were there in an attempt to bring Houdini news of his sainted mother Cecilia, who had died nine years earlier.

The three sitters joined hands and said a prayer. “I closed my eyes and eliminated from my mind all thoughts but those of a religious order, so that I could help as much as possible,” Houdini recalled.

For some minutes after that, Lady Doyle, who had recently begun to show a gift for channeling the spirits, sat motionless, poised over the blank writing pad before her. Then, with a jolt, the pencil in her hand began to move.

“It was a singular scene,” Conan Doyle later wrote, “my wife with her hand flying wildly, beating the table while she scribbled at a furious rate, I sitting by and tearing sheet after sheet from the block as it was filled up, and tossing each across to Houdini, while he sat silent, looking grimmer and paler every moment.”

By the time it was all over, Lady Doyle had produced fifteen pages seemingly full of the late Mrs. Houdini’s reflections on life and death. Among them was the statement, “It is so different over here, so much larger and more beautiful,” and concluding, “Tell [Houdini] I love him more than ever – the years only increase it – and let him know that I have bridged the gulf. That is what I wanted, oh so much. Now I can rest in peace.”

When they met in New York two days later, Houdini gave Conan Doyle the impression that he believed “My mother really ‘came through’… I have been walking on air ever since.” But perhaps it was another case of artifice by a master of the craft, because Houdini confided to his wife that he could only wonder why his mother would have chosen to communicate with him in fluent English, a language she had never spoken.

When two supremely self-confident propagandists meet and they are men of almost messianic belief in their own cause, the stage is set for a certain drama. What followed was the first recognizably modern, media-driven celebrity feud.

On September 3, 1922, Lloyd’s Sunday News published the first of twelve weekly installments of Conan Doyle’s book Our American Adventure. Among other things, the serial went into some detail about the events of the previous June in Atlantic City. This was apparently too much for Houdini, who, remarking that he had no intention of becoming known as a “confirmed spookist,” published his own version in the New York Sun. “I can truthfully say that I have never seen a mystery, and I have never visited a séance, which I could not fully explain,” he wrote. “There was not the slightest idea [in Atlantic City] of my having felt my mother’s presence, and the letter which followed I cannot possibly accept as having been inspired by her.”

Unsurprisingly, Conan Doyle was not pleased at this implied criticism of his wife’s mediumship. “Pray remember us to your good lady,” he wrote in his next letter to Houdini. “Mine is, I am afraid, rather angry with you.”

“The times hunger for something,” Houdini conceded in another letter, referring to the enormous worldwide losses caused by the recent war and the flu pandemic that followed. But he had crossed paths with too many of the singing clowns and card sharps on the old turn-of-the-century vaudeville circuit to take them seriously now that they’d reinvented themselves as spiritualistic mediums. “One must be one of the great dupes to accept it,” he wrote.

Things went downhill from there. Soon Houdini began performing his own medium-debunking stage shows in which he demonstrated how “so-called seers” swindled their clients. He went into print again calling Conan Doyle “a bit senile” and “easily bamboozled.” The author responded in a long article in the Boston Herald notable for its slight to Houdini’s Jewish ancestry. The magician was “as Oriental as our own Disraeli,” he wrote, a man “with entirely different standards.” When the paper asked Houdini to comment, he told them he felt “very sorry for Sir Arthur. It is a pity that someone [should], in his old age, do such really stupid things.”

This was mild compared to what happened at a noisy public performance in Boston in December 1922. “Conan Doyle states that even I am a medium,” Houdini announced. “That is not so. I am well done.” After the guffaws had died down, an audience member stood up to yell, “I will tell you one thing, you can’t fill a house like Conan Doyle did twice.”

“Well, all right,” Houdini shouted back. “If ever I am such a plagiarist as Doyle, who pinched Edgar Allan Poe’s plumes, I will fill all houses.”

“Do you call him a thief?”

“No, but I say that his story ‘Scandal in Bohemia’ is only the brilliant letter [sic] by Poe… I was in his room at the Ambassador Hotel and I saw twenty books, a paragraph marked out of each one of the detective stories. I don’t say he used them…” Houdini continued, but the rest of what he said was lost in the ensuing uproar.

Perhaps fittingly, the feud continued even beyond the grave. Houdini succumbed to peritonitis, possibly exacerbated by being punched in the stomach by an overzealous admirer, at the age of 52. “It was most certainly decreed from the other side,” Conan Doyle wrote, still as keen to recruit his rival to the spiritualist camp now that he was dead as he had been when he was alive. When Houdini’s widow wrote to reveal that a mirror had broken in her home, for no apparent reason, and that the thought had occurred to her that this might be some “manifestation,” Conan Doyle heartily concurred.

“I think the mirror incident shows every sign of being a message,” he wrote. “After all, such things don’t happen elsewhere. No mirror has ever broken in this house. Why should yours do so? It is just the sort of energetic thing one would expect from Houdini.”