Nietzsche trained as a cavalryman, but injured himself attempting an unorthodox dismount. His last public act was to throw himself sobbing around the neck of a flogged horse in Turin. In the decades after the philosopher was carried to the asylum, we put horses out to pasture. Our constant companions, first domesticated on the Eurasian steppe some four- to six thousand years ago, were displaced by a new symbol of mobility and freedom, the internal combustion engine.

In Farewell to the Horse (2017), the German historian Ulrich Raulff identifies the moment we abandoned our real four-legged friend as the moment we became modern — which is to say, lost amid freedom. If Americans are more lost than most, it is because they have more freedom than most. And because they have more freedom, they imprison more people. Philosophers call this the Kristofferson Paradox, after the rugby-playing Rhodes Scholar Kris Kristofferson (Merton College, Oxford): ‘Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose, / And you ain’t nothing if you ain’t free.’

As Kristofferson’s career shows, the cowboy haunts the imagination of white American men like the ghostly horseman in Rembrandt’s Polish Rider. The word ‘cowboy’ fuses animal and man, like centaur for the Greeks: an image of balance, transformation, mobility, divinity. To ride a horse, you must remain centered. But there is no center in American life, only extremes. The United States has lost its moral, fiscal and strategic balance. The world, as Osama bin Laden said, looks to the ‘strong horse’.

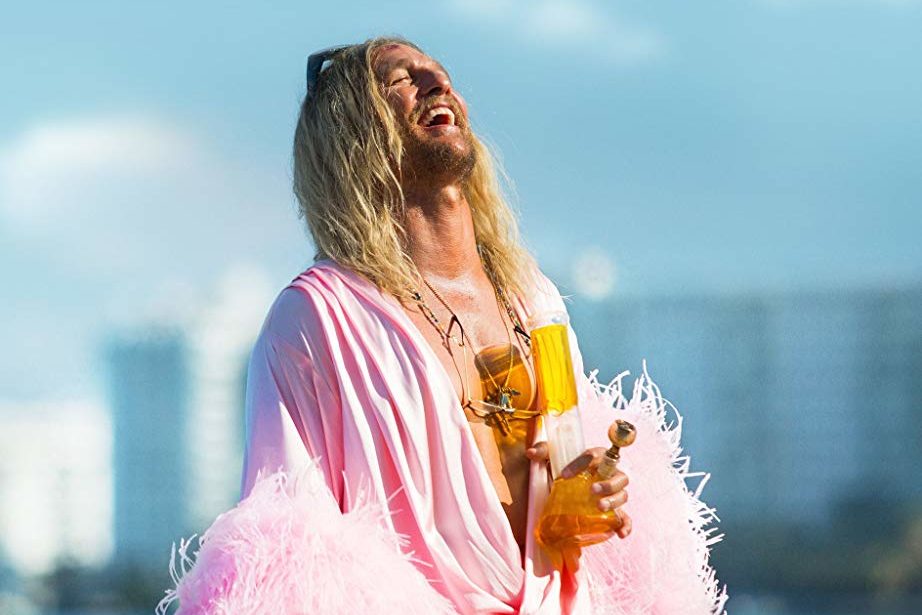

Watch The Mustang after The Beach Bum, and you see exactly how the most powerful society in the world came a-cropper. The Beach Bum, directed by the effortlessly sordid Harmony Corine, is a parasite of a film about a parasitic way of life. Moondog (Matthew McConaughey) is a crass derivative of the The Dude from The Big Lebowski. A writer of sub-Beat verse, he lives in Key West. Moondog wears various shades of Tommy Bahama, is perpetually stoned and drunk, and lives off his wife’s money. He has infinite freedom, and no sense of obligation to any else.

I did wonder if this set-up was an allegory for American fiscal policy, and whether Moondog’s deficits would catch up with him in the end. But The Beach Bum turned out to be nothing more than an immature and coarse tribute to the nihilist philosophy of Jimmy Buffett and Snoop Dogg, both of whom foul their cinematic shorts by appearing in this film, along with a rotating cast of marijuana bongs, naked black women with large bottoms, comedy Rastas, sports cars, power boats, and more naked black women with large bottoms. This is how the cokey children of white America are wrecking the place. They’re diddling while Rome burps.

The Beach Bum has no convictions, only gratifications. The Mustang, directed by Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, is all about convictions and gratification — convictions for murder and armed robbery, and the impossibility of attaining the gratification of forgiveness, which is one of the few ways to feel truly free. Roman Coleman (Matthias Schoenaerts), imprisoned for the attempted murder of his wife in a fit of rage, is estranged from the rest of his species, including his 16-year-old daughter (Gideon Adlon), who is now pregnant and seeking to cut her last, financial connection with him.

A counsellor enrolls Roman in a rehabilitation program for violent offenders which trains wild mustangs. These programs exist, and their graduates, when paroled, have a significantly lower re-offending rate. The old cowhand Bruce Dern plays Myles, the ancient rodeo rider who runs the training program. Clermont-Tonnerre describes Roman’s struggles with the animal within and without, and the animalized world of the prison, in almost documentary terms, with the minimum of sentimentality and the maximum of feeling.

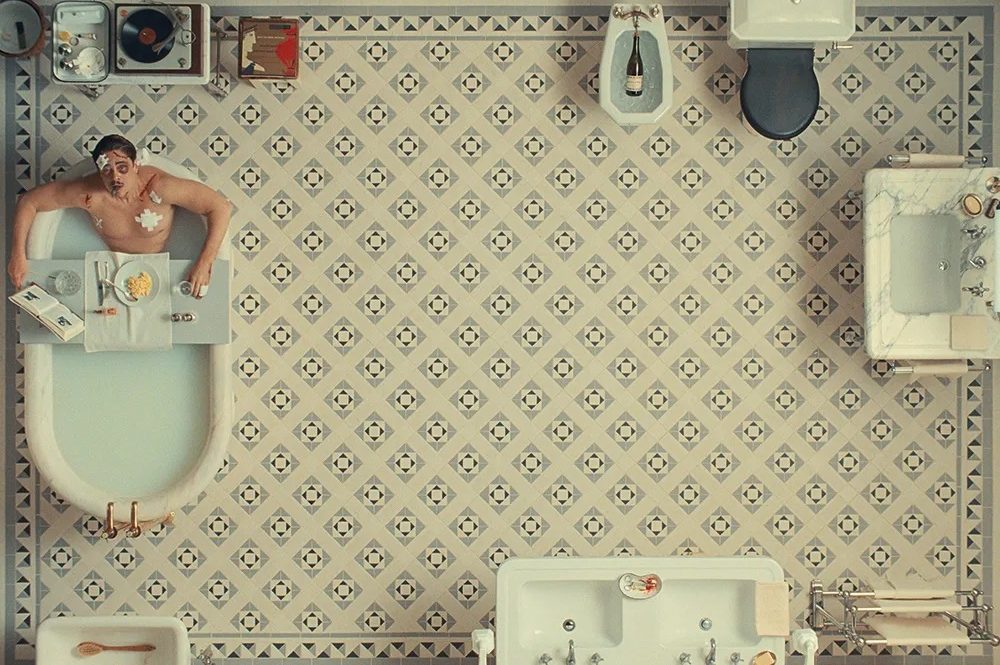

The Mustang’s executive producer, Robert Redford, is currently engaged on an endless autumn of elegies for white masculinity. I last saw Schoenaerts, who’s fired by high-horsepower internal combustion engine, in the underrated Racer and the Jailbird, where bank heists and car chases masked a Kristoffersonian reflection on how the drive to absolute freedom is a drive to death and prison. But the film that The Mustang really reminded me of was National Velvet (1944), only with the location changed from wartime England to a Nevada prison, and the rationed commodities changed from sausages to drugs — if, that is, you can imagine the young Mickey Rooney stabbing a fellow coach in the neck with a homemade shiv.

Then again, imagination requires freedom, and freedom is meaningless without restraint. A rider must maintain ‘contact’ with the bit, even when, like Roman, he remains in solitary. This, the lesson that horses teach us, is the moral of The Mustang. As Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder showed in Stir Crazy (1980), horses make us free. The prison-house of impulse and exploitation in The Beach Bum, or the liberation of inner harmony and horse sense in The Mustang? Like the philosophers say, you’re free to choose.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.