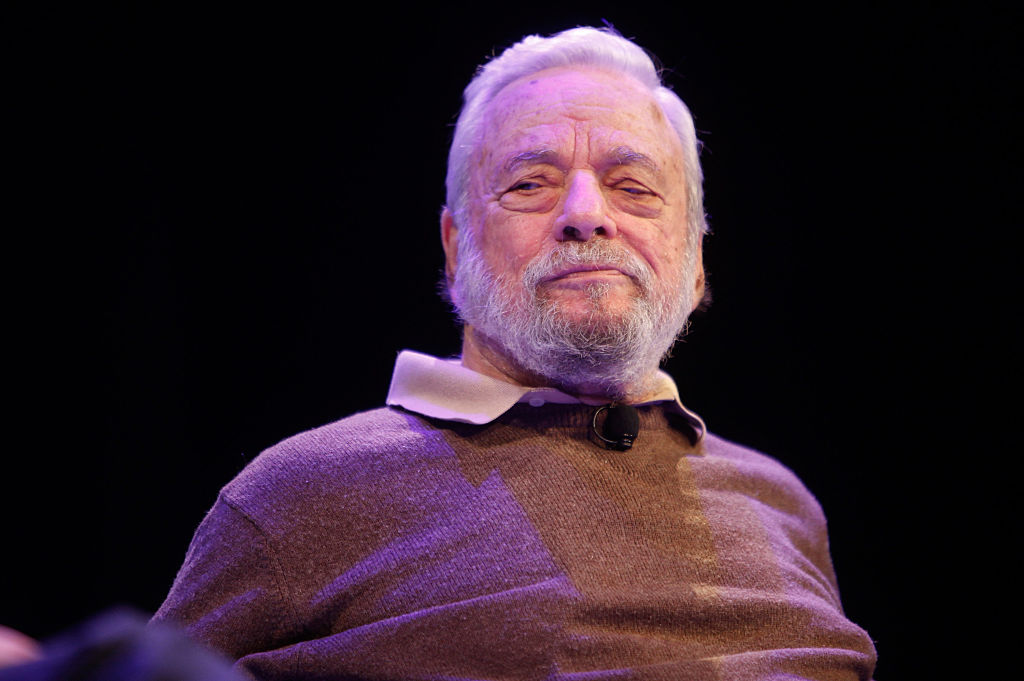

“I have always conscientiously tried not to do the same thing twice,” American composer and song-writing legend Stephen Sondheim once told the New York Times Magazine.

In his final ever musical, conceived over a decade ago and executed after his death aged ninety-one in 2023, Sondheim has once again, like a magician, conjured surprise. Here We Are is many things and it isn’t always successful. But this maverick musical is wildly original — not least in suspending the songs themselves almost entirely for the second act.

While Sondheim has, in the past, delved into a dizzying array of genres — from an updated Romeo & Juliet (his big break came when he was asked to write the lyrics to West Side Story), to a penny dreadful (Sweeney Todd) and the modern reworking of fairy tales (Into the Woods). Here he delves into surrealism, territory where few musicals have dared to tread.

With a book by playwright David Ives, Here We Are is based on two Luis Buñuel films: The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Exterminating Angel. In the first, which forms the plot for Act 1: The Road, a group of wealthy friends attempts to eat in a series of restaurants, while somehow never getting fed. In the latter, which forms the plot for Act 2: The Room, and is far darker and more disturbing, a dinner party turns desperate when the participants realize they can’t leave.

Here We Are combines these two stories together, with an astonishing, pitch-perfect cast. One morning ruthless business titan Leo Brink (Bobby Cannavale at his brash, braying best) and his sweet oblivious wife Marianne (the sympathetic Rachel Bay Jones) are accosted by friends at their home who claim they’ve been invited for brunch.

Unprepared but game (Marianne heads out in her flowy blue négligée and fluffy heeled slippers and Leo offers to foot the bill), the couple go in search for food with plastic surgeon Paul Zimmer (Jeremy Shamos), his abrasive agent wife Claudia (Amber Gray), and the smooth-talking ambassador of the fictional country Moranda, Raffael Santello Di Santicci (Steven Pasquale). Marianne’s sister Fritz (Micaela Diamond), a hypocritical champagne socialist who believes she is part of the revolution yet is the fussiest customer of the lot, joins for the ride.

The group drives to a series of different eateries, but, for various reasons, the waiters are never able to provide a meal. Frustrated, the friends, alongside some hangers-on (a colonel and a handsome soldier, both less fully sketched than the main five), descend on the Moranda embassy for dinner. Finally, they are satiated. But when they attempt to leave the palatial room where they are lounging after gorging on the feast, they find they can’t.

Trapped, without even basic facilities (a Ming vase serves as a toilet) or food, their baser nature emerges. This is tempered by a kind bishop (the euphoric David Hyde Pierce, of Frasier fame), who survives on eating the pages of Dickens in the library. As he shrugs with resignation: “The classics. Always nourishing — now literally so.”

Sondheim, who admitted to his propensity to procrastination, started Here We Are over ten years ago, but struggled to finish it. Just two months before his death in 2021, he gave the green light, telling Stephen Colbert on his late-night show: “We had a reading of it last week and we were encouraged. So, we’re going to go ahead with it.”

Producers claim that Sondheim also agreed that the second act would be light on songs: as the characters descend into a nightmarish Groundhog Day, stuck for countless days and nights by some invisible force, they have no reason to sing. The decision essentially turns the second act into a play, finished, after Sondheim’s passing, by Ives and director Joe Mantello. (All the lyrics and songs, meanwhile, are Sondheim’s).

That this evisceration of the one percenters is very much on trend — explored in recent hit TV shows such as The White Lotus — does not detract from its sharpness, delivered with typical Sondheim wit and wordplay. (It is no surprise that Sondheim was once tasked with inventing cryptic crosswords for magazines.)

Marianne and Leo are the kind of couple who wants to clone their dogs — not to remember them when they die, but so they can have a set of the pets in each of their many houses, and don’t have to bother with the hassle of transporting them. Paul is eager to celebrate his 1,000th nose job. Fritz pays lip service to toppling the social hierarchy but orders a burger with so many caveats she might as well be a celebrity in Beverly Hills.

Summing all this up is the scraping, bowing apologies of a waiter (Denis O’Hare) at the Café of Everything who has run out of, well, everything. It is painful and funny, while revealing the expansive tastes and expectations of a spoiled urban class. “We do expect a little latte later / But we haven’t got a lotta latte now,” sings O’Hare.

And yet the first act feels exhausting rather than illuminating. Some of this is due to a repetitive plot that goes nowhere (the musical was originally titled Square One); some to David Zinn’s set, a gleaming white box presumably meant to mimic the cavernous and sparse spaces of the super-rich. Both left me cold.

True, the characters were compelling: in particular, the charming and boorish shark Leo, dressed in a gummy red velour tracksuit, and the raffish Raffael, snappy in a white linen suit and white shoes, who oozes across the stage and tirelessly tries to bed every female in sight. But I found all the back and forth, the pitter-patter, tiring, and the premise superficial.

Act Two is a warmer, more complex experience, as reflected in the set design. The white box is swapped for a sumptuous embassy drawing room, replete with rows of leather-bound books, comfy armchairs, candles and gold gilt. There’s even a butler. As the stage recedes and is brought into focus revealing the banquet, it looks, at times, like a Renaissance painting.

It is here, too, as the group faces mortality, that we finally find not only smart-aleck quips but some real heart. At one point, while the rest of the crew are sleeping, Marianne dances with an enormous bear that emerges out of the shadows. It is unclear if this is a dream or a hallucination or real: but her slow waltz is beautiful. And, somehow, this sequence illustrates the weirdness of the world far more than the fast-paced rat-a-tat-tat of the first act. That the songs stop — even the piano won’t work — doesn’t detract from the performances but allows for some moments of reflection and quiet. Not least a discussion between Marianne and the bishop on what it means to just be: to exist, here, right now.

Here We Are is in many ways confused: It is unsure whether to mock and serve up its characters on a platter or to understand and humanize them, offering redemption. It is saved by its impeccable, giddy-making cast. But whether Here We Are can, and will, outlive this specific production, which is anchored and finds gravitas by being pitched as Sondheim’s last musical, time will tell.

Leave a Reply