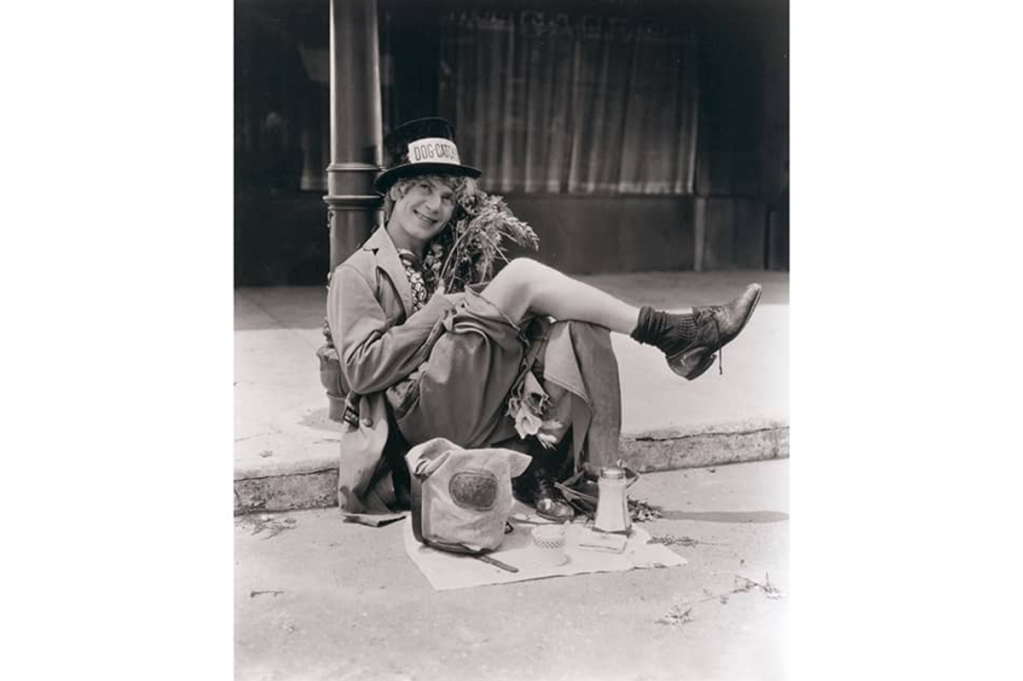

It’s hard (if not impossible) to imagine a world worth living in that doesn’t include the Marx Brothers; and equally impossible to imagine the Marx Brothers without their forever silent, animal-loving, hilariously unpredictable Harpo, he of the moppet wig, trampish overcoat packed with stolen silverware and blow torches, and recurringly grotesque facial expressions. For while the greatest comic performers of the silent film era (such as Chaplin and Keaton) couldn’t speak to the camera, Harpo was the only comic of the talkie era who simply wouldn’t, as if human conversation were somehow beneath him.

There was always something about Harpo that seemed a little better than the ridiculous world he inhabited, as if he spiritually resided way out beyond the stratospheric clouds of absurdity. As Joe Adamson wrote in 1973, when the Marx Brothers films were being enthusiastically rediscovered on college campuses and film repertory movie screens: “Harpo’s actions bespeak an ethereal freedom that is immediately recognizable as something we know nothing about.” Which is probably why so many of us enjoy him.

The second of five sons born in Manhattan to Jewish immigrants — the legendary stage mom Minnie and her husband Sam, a poor excuse for a tailor and a great excuse for a family chef, known as “Frenchie” — Adolph (Harpo) Marx enjoyed what he happily recalled as an impoverished life, one in which he roamed the streets selling stolen items at pawn brokers, or doing chores for nickels. He quickly learned to be happy with what little he possessed while he had it, since his ne’er-do-well older brother Joseph (known as Chico, as in “he’s off chasing another chick, oh”) would almost instantly steal it, sell it and use the money to gamble himself further into debt.

All five of the brothers eventually followed their uncle Al Shean into vaudeville, singing, dancing and engaging in comic skits that often played off the motley urban accents of their neighborhoods — Irish, Italian, Yiddish and German. They formed a fairly successful singing group called the Five Nightingales, and by their thirties developed the characters that would make them famous for the rest of their lives: Groucho, of the painted on mustache and diamond-sharp insults; Chico, of the Italian malapropisms and finger-pistol piano playing; and possibly greatest of all, that wildly smiling imp of the perverse who never spoke and never needed to, since he could easily express his deepest emotions through playing either an angelic harp or a lasciviously beeping car horn.

Harpo’s was a weird, kinetic intelligence which made him seem like either a genius or an idiot savant. At one point, early in his stage career, he was given a harp by his mother to bring more musical variety to their act. Within months, Harpo taught himself to play it, and continued teaching himself instruments throughout his life, including the piano, clarinet and harmonica. When accomplished harpists came over to show him a few things, they were soon dispatched with notebooks full of idiosyncratic new techniques they never lived long enough to master. “Harpo was the solid man in the family,” Groucho recalled in Groucho and Me (1954). “He inherited all of my mother’s good qualities — kindness, understanding and friendliness. I inherited what was left.”

Unlike his brothers, Harpo didn’t have a cruel or selfish streak in his nature; and he was usually recalled with great fondness by everyone who knew him. It comes as no surprise then that this loving, gentle, unpretentious and long-unpublished memoir by his wife of nearly forty years, Speaking of Harpo, lacks any of the bitterness and recriminations of the usual “tell-all” Hollywood autobiography.

When Susan Fleming moved to Hollywood in 1929 to work through the Depression in a series of increasingly minor film roles, she met Harpo at a dinner party given by Samuel Goldwyn and began one of Hollywood’s happiest, longest engagements. While Harpo was more than twice her age, he usually managed to act half as old, and over the next several years he remained committed to his bachelor existence at the notorious Garden of Allah Hotel, where he endlessly partied with the likes of Alexander Woolcott, Robert Benchley, H.G. Wells, F. Scott Fitzgerald, George Bernard Shaw and Dorothy Parker. (It is one of the many happy ironies of Harpo’s life that a man known for speaking not a single line of dialogue kept a seat at the Algonquin Round Table — largely, he claimed, as audience rather than participant.)

Unlike Chico, Harpo soon gave up drinking and womanizing; and eventually he and Susan went off to be married by a fire station chief in Orange County. (They kept it a secret from the studios for many weeks.) They went on to adopt four children, build a large home in Riverside County (El Rancho Harpo) which often looked like a huge playroom, and decided to live without servants. Instead, Susan learned to cook and sort out the finances while Harpo went off on occasional team tours with the always money-strapped Chico. When he was home Susan often found him in the middle of the night playing jacks with their daughter on the bathroom floor, or rushing back in the afternoon to listen to Uncle Whoa Bill, a children’s daily radio show, with their five-year-old son.

In fact, these radio programs resulted in one of this book’s few regretful memories: Susan’s failure to pick up on Harpo’s hints that he wanted her to alert the producers about his birthday, so Uncle Whoa Bill could announce a treasure hunt for him, as he did for his child listeners. “That show was so moronic,” Susan explained many years later to her critical son, “I couldn’t imagine even your crazy father listening to it.” But she never forgave herself.

Speaking of Harpo is an almost relentlessly cheerful book about a happy marriage, and there’s hardly much that seems scandalous or surprising about it — with the possible exception of an anecdote about Marlene Dietrich sitting on a tennis court bench, removing her panties and performing a series of Basic Instinct leg crosses during a match. Otherwise, the only vituperation Susan expresses is almost exclusively reserved for Harpo’s brothers. The endlessly dissolute Chico once embarrassed his daughter by hitting on one of her teenage friends at a high school function, while Groucho liked to save his cruelest insults not for the contestants on You Bet Your Life but for his three wives. (None of them were “long-suffering,” though, since they each soon divorced him.)

In our cynical times — especially regarding Hollywood celebrities — this is a delightful read. Susan originally wrote it in response to taking a creative writing course in the early 1980s, and later collaborated on revisions with Robert S. Bader, who had previously worked with Harpo on his naturalistic, verbally effusive memoir, Harpo Speaks! (1961). Then, after Susan lost interest in the project (she is clearly not a self-aggrandizing personality — another quality that makes this book refreshing), and her death in 2002, the manuscript gathered dust until Bader recovered it, rewrote passages and finally released the completed book. Yet, despite many decades of gestation, Speaking of Harpo feels freshly written, as if Susan’s voice is speaking brightly to us from a time that seems like today — just as she writes how, even thirty years after Harpo’s death, she could still hear her devoted husband conversing in her head about all things great and small.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.