Maggie O’Farrell is much possessed by death. Her first novel, After You’d Gone (2000), chronicled the inner life of a young woman who finds herself comatose following a near-fatal car accident. And a recent piece of non-fiction, I Am, I Am, I Am (2017), gave an account of O’Farrell’s own numerous brushes with mortality.

Her latest novel returns to this preoccupation with the ‘undiscovered country. from whose bourn/ No traveler returns’. In it she sets out to tell the imagined story of the life and death of Shakespeare’s only son, Hamnet, who perished at the age of 11, four years before his father wrote the play that would share his dead son’s name — in Elizabethan England, the spellings Hamnet and Hamlet were interchangeable.

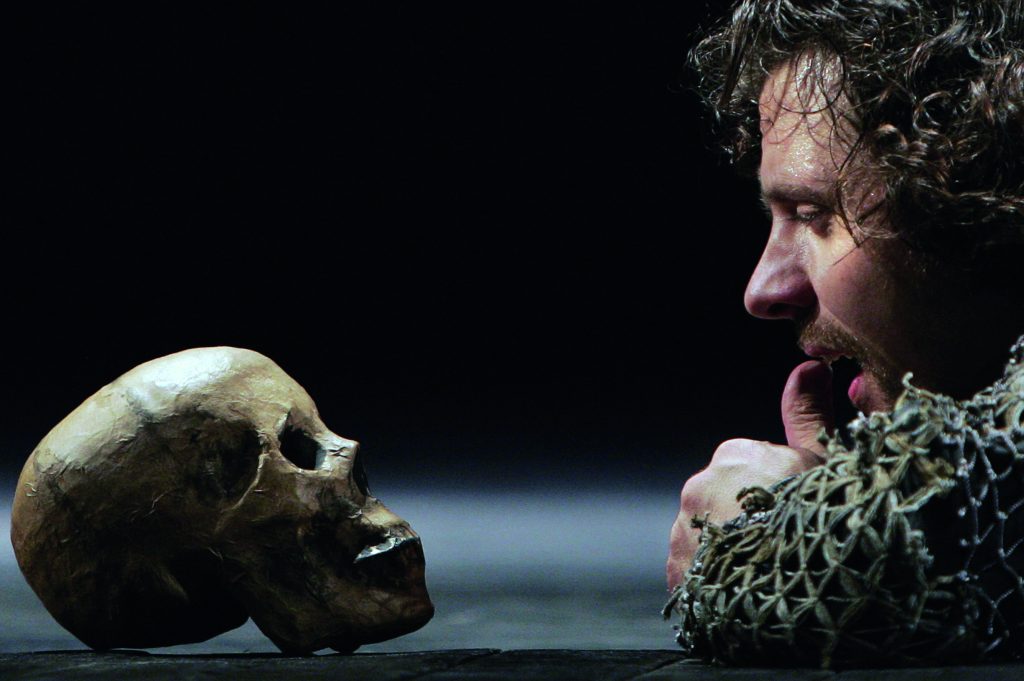

O’Farrell opens her narrative with the young boy moving through the rooms of the houses of his parents and grandparents in search of assistance for his twin sister, Judith, who is ill in bed with chills, a fever, ‘a swelling at the base of her throat’ and ‘another where her shoulders meet her neck’. There is no help to be found. His tender father (who is never named) is away working in London. His older sister, Susanna, is nowhere to be seen. His violent and tyrannical grandfather, John, is not in his workshop making gloves. And his mother, Agnes, is off gathering herbs for the creation of simples, potions and curses. Accordingly, Hamnet is left to face alone the prospect that his twin might have the plague. It is an episode of solitude that will haunt his mother, ‘will lie at her very core for the rest of her life’.

With this scene in place, O’Farrell takes us back to young Shakespeare’s days as a reluctant Latin tutor to the family of Agnes Hathaway, a mysterious woman — ‘too dark… too silent, too strange’ — with whom William falls in love. (She is Agnes, rather than Anne, throughout the novel). The plot then moves back and forth, with extraordinary elegance, between the week Hamnet spends with his sisters in the summer of 1596 and the tale of his parents’ meeting, courtship and marriage. Shakespeare was 18, Agnes 26.

The result is astonishing. The chapters in which we see the plague take hold of Hamnet’s sister (who would eventually recover), and then migrate to him, induce a sense of rapt dismay, while those that chart the burgeoning relationship of Agnes and William quiver with erotic and affective promise and display an imaginative capacity (particularly in the descriptions of Agnes) that is richly and attentively empathetic.

[special_offer]

There are occasional shortcomings. O’Farrell has a habit of using inert phrases such as ‘stops in her tracks’, ‘turns on her heel’, ‘sidles up to her’, ‘driving her to distraction’. But these infelicities only stand out because they are surrounded by so many instances of careful observation and serious noticing. She has a particular talent for harnessing the resonance of the seemingly negligible detail, and the part of the book that attends to the effects of Hamnet’s death offers a picture of bereavement that amounts to one of the most painfully and cathartically humane depictions of grief you are likely to encounter.

In this, as in so much else, Hamnet serves as a bewitchingly sensitive register of the ‘vibrating interior’ of the lives of others, and a work that takes intimate measure of the lineaments of the undiscovered country.