The death of Joseph Conrad made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of blank in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included.

For John Le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their Biblical origins, mining the Gospels rather as Le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America.

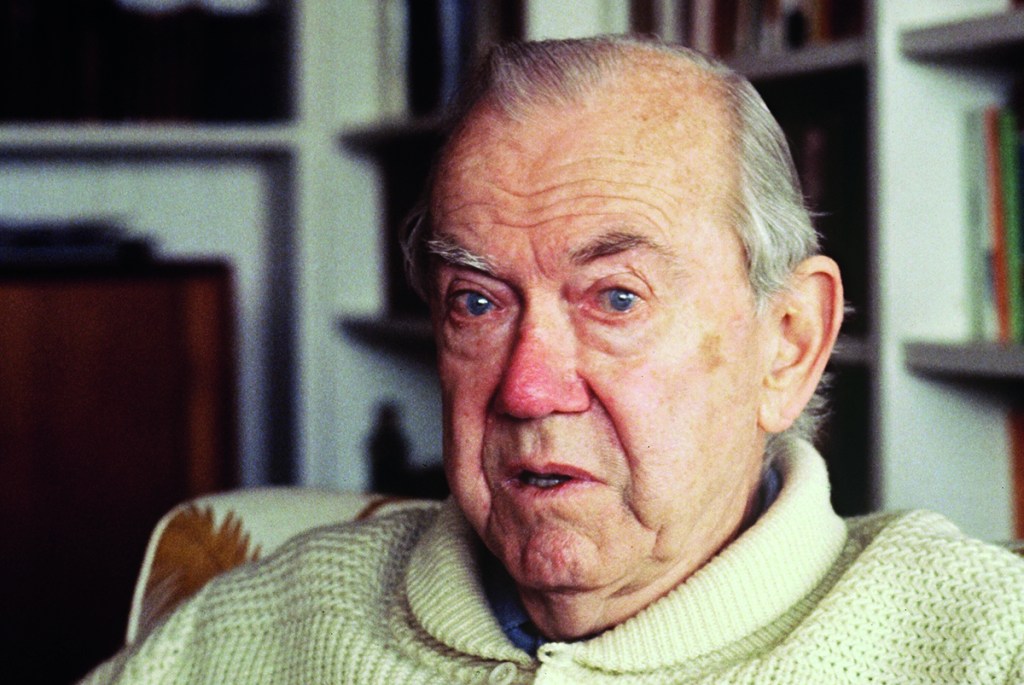

About Greene’s character, less consensus reigns. Congenitally elusive, he refused to appear on television. ‘I feel I’ve got a copyright on my life,’ he explained to me, ‘and that people I know should have a copyright on theirs.’ How much of his secretiveness was vanity is hard to tell. Unable to pronounce the letter ‘r’, his instinct was for self-effacement — ‘I am so shy’ were his first words to Kim Philby’s Russian wife. Yet cohabiting the same skin — ‘faintly sunburned, with the texture of fine dry silk,’ recalled one mistress, Jocelyn Rickards — there writhed a provocative exhibitionist whose lovemaking with Rickards as they traveled first class by train to Southend was conducted in blatant view of those on the platforms.

Definitely, there were aspects of his life that he hated, even if others thought it a good thing to be him, and pinched his identity. When Greene learned of one impersonator being jailed in Assam, he proposed to interview him for Picture Post. But his double jumped bail, so the real Graham Greene couldn’t visit India for fear of arrest.

Haiti’s repressive dictator ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier was another leader who thought he knew him, and in 1968 authorized an early biography: Graham Greene Démasqué, a hurried collection of essays exposing Greene as an opium addict, spy, racist, pervert, swindler and torturer. At the opposite pole stands Greene’s dogged official biographer Norman Sherry, whose three-volume life consumed 28 years and is generally viewed as a lost opportunity. Despite shelves of books on Greene, it’s as if his character has escaped, like his incarcerated double, through the cracks he hammered out for himself.

Greene’s avoidance of publicity was part of a myth he orchestrated. He wished to back into the limelight on his own terms. When he did so, it was under the obscure direction of amateur video cameras, or in a fleeting cameo in François Truffaut’s 1973 film La Nuit américaine (Day for Night), playing an anonymous insurance salesman called Henry Graham, Greene’s baptismal names. A year before Greene died, I even suggested that he script his own obituary and transmit his first full-length television interview from beyond the grave. He found the idea ‘very amusing and macabre’, but was too ill to participate, ‘and anyway I think I have been giving out too many opinions and memories already in book form’.

Since his death, pressure has intensified for a sensible one-volume life that clips away the myths and controversies hedging him and brings together new sources. Thirty years on, the publication of The Unquiet Englishman is cause for celebration. A professor of English at Toronto University, and no relation, Richard Greene has already edited a valuable collection of Graham’s letters. Taking the high view that his subject is ‘one of the most important figures in modern literature’, and that previous biographers ‘lost sight of what mattered’ in focusing on ‘the minutiae of his sexual life’, he gives us a nicely written and well-judged cradle-to-grave portrait that needed to be conventional and unshowy and is all the better for it.

Richard Greene takes as his central motif one of Greene’s famous episodes, the Russian roulette he played as a schoolboy to ward off chronic ‘boredom’, later diagnosed as manic depression. After a total of six plays with a small ‘ladylike’ revolver apparently discovered in his bedroom, he gave up. Both his brother and mother disputed this story, as does Richard Greene, who concludes that he did play Russian roulette, ‘but with blanks, or more likely empty chambers’.

Nonetheless, Greene whittled this into a personal myth to explain a recurrent pattern of reckless escapes: to Liberia, Mexico, Malaya, Kenya, the Congo, Cuba and Vietnam — where ‘fear of ambush served me just as effectively as the revolver from the corner cupboard’. Wagering his life again and again, writes Richard Greene, ‘his most ingrained habit was survival’. And in the discrepancy between those ‘just republics’ he initially imagined he would find — based on his childhood reading, ‘where a man can make his fortune without fuss and bother’ — and what he actually found, he staked his claim to another landscape. In 1940, Arthur CalderMarshall dubbed it ‘Greeneland’.

Greeneland is commonly a frontier zone in the back of beyond where the pervading smell is the police station; the usual time of day the pink-gin hour on the veranda; the only certainties those possessed by children. Over the border posts, God and the Devil wheel like vultures, and a loose fence separates the good man from the bad. For the rest of his life, Greene was attracted to this torrid region like a bluebottle.

A paradox of Greene is his constant buzzing after a borderland which might promise not only escapist thrills but equilibrium — and where, like his double agent Maurice Castle in The Human Factor, ‘he could be accepted as a citizen without any pledge of faith, not in the City of God or Marx, but the City called Peace of Mind’. Yet it was in his unsettled personality always to take sides, ‘even if my choice might only be for a lesser evil’. Hence his frequently incendiary remarks about America’s foreign policy, such as this corker involving Panama’s pockmarked dictator, Manuel Noriega: ‘If I have to choose between a drug dealer and United States imperialism, I prefer the drug dealer.’

It was an article of Greene’s congested faith that relationships with individuals were more important than those with countries. Even so, Greene routinely betrayed or declined involvement with those closest to him — his wife, his two children, his lovers. ‘I wish I could stop being a bastard,’ he wrote to Catherine Walston, his most passionate mistress. Unsurprisingly, this streak of disloyalty, which he interpreted with characteristic perversity as a virtue in others, contributed to regular bouts of self-loathing and feelings of suicide.

It was easier to help strangers — which maybe explains his generosity towards underdogs and dissidents, and, most controversially, his stubborn loyalty to Philby, under whom he had served in wartime Intelligence. Still, Richard Greene questions the moral principle behind it: ‘It suggests a failure of imagination; one cannot put a value on the pains of people one has never met, and that is what novelists claim to do in their art.’ Likewise, he finds dubious Greene’s argument for the moral equivalence of crimes committed by the East and West. ‘Even allowing for the outrages of American foreign policy, it is hard to equate them with those of Stalin and his successors.’ Perhaps Greene’s deeper flaw was to confuse his preeminence as a writer with a degree of political thinking he did not possess.

Richard Greene has mastered a tremendous amount of material. Greene’s travels and friendships spanned a world undergoing unusual political upheaval. His published works encompass journalism (including 600 film reviews for this magazine), plays, biographies and 26 novels. The result is a pared-down portrait that keeps to the track, but knows when to race ahead to tell us information to which we need not return — although, in his declared intention to avoid the salaciousness of his predecessors, Richard Greene walks sometimes too far down the plank of discretion.

Greene appears to be contentedly married when we suddenly discover he’s been having an 18-month affair with a prostitute called Annette. Nor is Greene’s wife unique in successfully preserving copyright on her life. Once, from Dakar, Greene wrote to Catherine Walston: ‘You’re my human Africa…I love your dark bush as I love the bush here.’ Regrettably, few bush telegraphs survive to other important mistresses — Dorothy Glover, Anita Björk and Yvonne Cloetta, the companion of his last 36 years.

In childhood, Greene had envied the fate of Wilfred Ewart, shot during an uprising in Mexico. At our last lunch, at Chez Felix, after one and a half carafes of Cogolin, I asked:

‘How would you like to die?’

‘I’d prefer a bullet rather than a lingering illness.’

‘Would you like a bullet?’

‘Yes, I’d quite like a bullet.’

In the end, there was no Papa Doc assassin or French mafia bomb blast. ‘He was only ever hunted by himself,’ reflected Yvonne Cloetta, ‘a victim of the traps that, incorrectly or not, he had set up against himself.’ His latest and best biographer observes: ‘It would be hard to improve on that insight.’

Richard Greene’s The Unquiet Englishman: The Life and Times of Graham Greene is published by W.W. Norton ($40). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2021 US edition.