“You can go ahead,” said the voice at the other end of the telephone. “The DPP has decided not to prosecute.” It was the call that allowed the publication of Lolita, one of the greatest gambles of George Weidenfeld’s career.

The moment George — it is impossible to think of him as anything other than George — had read this controversial book, available from the Olympia Press in Paris, known for its pornographic list, he had wanted to publish it himself; but as the law then stood, it would have been pulped immediately, owing to its story of a middle-aged professor who becomes obsessed with a twelve-year-old girl and kidnaps and sexually abuses her. The only glimmer of hope was that a new obscenity bill was being piloted through parliament, which proposed that if a work could be proved to have literary merit, it could be published and sold freely.

Mick Jagger’s ghosted autobiography, with its £2 million advance, never made it into print

Finally, in August 1959, it was passed, and 20,000 copies of Lolita were printed and shelved to await the verdict of the Director of Public Prosecutions. Would there be a prosecution and, if so, who would win the court case? The DPP remained silent, the copies stayed on the shelves and the uncertainty was agonizing. Finally, in November, came the fateful telephone call, and seemingly within minutes all 20,000 copies had flown out of the bookshops, to be followed by edition after sell-out edition. The thumping profit set the fledgling firm of Weidenfeld & Nicolson on a secure financial footing as well as being a personal triumph for George.

He was in every way an extraordinary man. Clever, ambitious, steel-willed, ferociously energetic, idiosyncratic and so gregarious that one of his four wives later complained that they only had two tête-à-tête evenings during their marriage. Virtually everyone who knew him had a George story, the commonest being that if you sat next to him at dinner at some point he would turn to you and ask you to “do a book” for him. (Here I must add that my own arrival in the Weidenfeld stable was through more conventional means.)

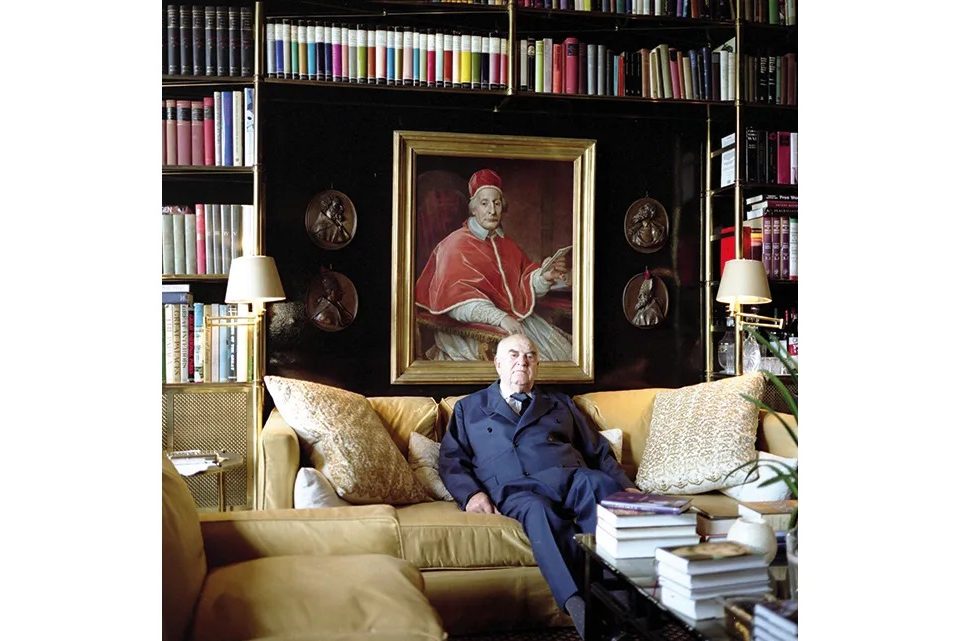

From an apartment with no running water in a poor quarter of Vienna, this amazing man rose to a seat in the House of Lords, with a heap of awards and an address book filled with the great and the good of three continents. His sumptuous Chelsea apartment was so crammed with wonderful pictures that some had to be hung on the curtains draped proscenium-wise over the dining room windows because there was no space for them on the walls.

Thomas Harding’s account of George’s life is not a straightforward, cradle-to-grave biography but an episodic story, with each chapter hinging on a different book, mostly published by W&N. Alternatively, it as a history of the golden age of publishing from the perspective of one man and, as this, it is fascinating.

It begins with Weidenfeld’s mother’s diary in a chapter entitled “Arthur” (George was born Arthur George Weidenfeld in September 1919), and his flight to London as an eighteen-year-old after the Anschluss in March 1938. Then comes “The Goebbels Experiment’,” the title of his first published book, covering his wartime work as a translator at the BBC; the change of his name to George at the behest of a producer; his desire to become a publisher, and the securing of the necessary paper by bringing out a turgid tome, A New Deal for Coal, by the future Labour prime minister Harold Wilson.

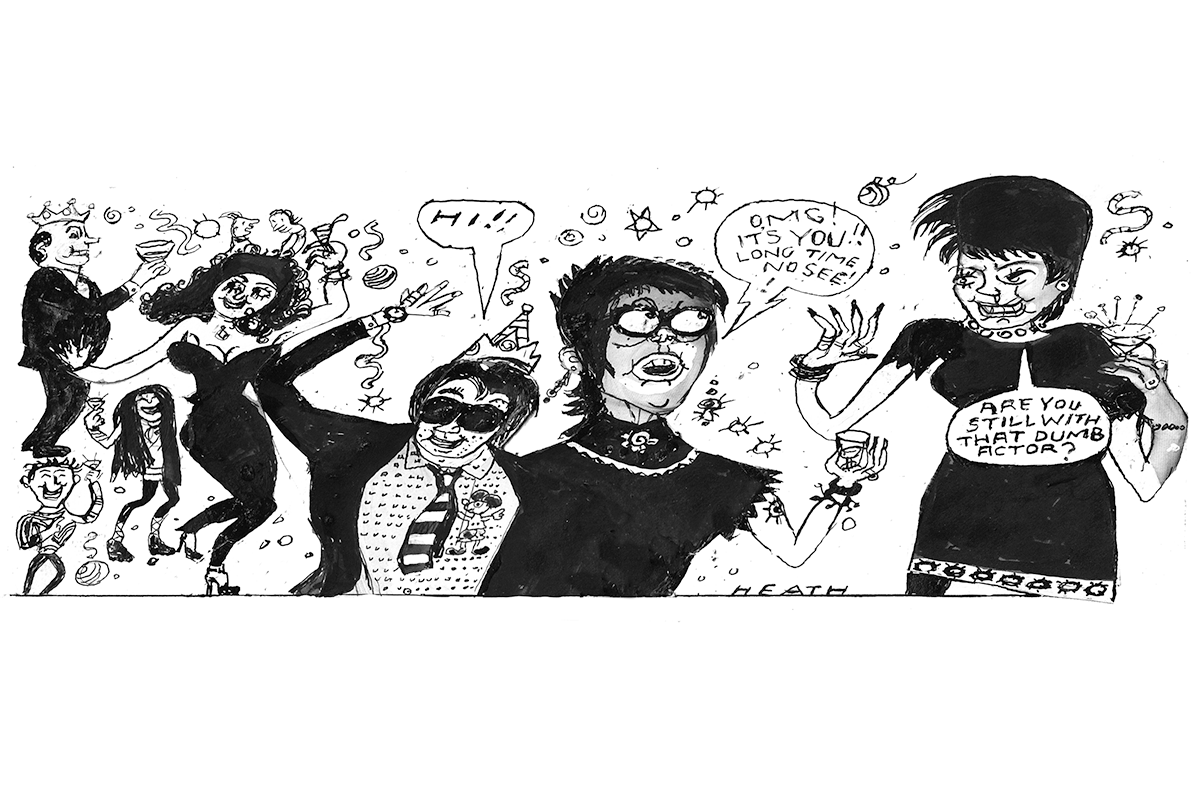

Here, too, is the seminal meeting (over lunch; entertaining was for George an essential tool from the start) with Nigel Nicolson, the son of two famous parents and with enough money to launch a publishing firm. The pairing of Jewish refugee and quintessential English gentleman would later be caricatured in Private Eye as Snipcock and Tweed. “Mary Queen of Scots” announces the arrival of Antonia Pakenham (later the writer and historian Antonia Fraser) as an editorial assistant. George had sat next to her mother at dinner.

The heading of another chapter, “The Group,” is the title of Mary McCarthy’s famous novel, but it could just as well refer to George’s women, an aspect of his life perhaps too lightly touched on by Harding. After numerous youthful conquests (there is no mention here of the “pretty Swedish au pairs” he once spoke of), he married Jane Sieff, the daughter of Marcus Sieff, of Marks & Spencer fame, then aged twenty to George’s thirty-two. The marriage lasted just four years but it left George established in Chester Square, one of London’s grandest addresses.

Then came Barbara Skelton. The advent of thifarouche, green-eyed houri, at the time married to Cyril Connolly, launched a cat’s-cradle tangle of husbands, lovers and authors. Barbara was an aspiring writer, and Connolly was published by George; Barbara and George fell obsessively in love; Connolly divorced Barbara, citing George; George married Barbara, then divorced her, citing Connolly.

Later she recounted the whole saga in her devastatingly frank memoir Tears Before Bedtime. Just before it came out, I interviewed her for a newspaper. George, who had somehow got wind of this, rang me. “What did she say about me?” he asked nervously. Not having the heart to tell him, the only words that sprang to my lips were: “She said you had a very hairy back.” There was a groan and the sound of the receiver being replaced. (Another of George’s quirks was dispensing with the formality of farewell once he had learned what he wanted.)

In July 1966 came a very different marriage, to the pretty American heiress Sandra Payson Myer, aged thirty-eight (George was then forty-six). He later described her as “a tall, imperious blonde with a Vanderbilt face and marvelous cheekbones.” But her bone structure was not enough to save the marriage; with three teenage children, she necessarily had to spend a lot of time in the US, and this, with the long hours George worked, spelt the end.

Between Sandra and his fourth and final, happy marriage (in 1992) to the beautiful Annabelle Whitestone, twenty-six years his junior, came a liaison with Barbara Amiel (now Lady Black), an affair made famous in Amiel’s no-punches-pulled memoir:

He was… exceptionally clever, with an extra-ordinary sense of humor embellished by a wonderful ability to mimic anyone… Unfortunately, he was also very short, plump and with eyes that could protrude rather alarmingly, especially when upset. And he became alarmingly obsessed with me… The minute I heard George’s suggestion “Let’s spend a cosy evening,” I went into semi-paralysis with dread.

Here Amiel gives rather too intimate details of the encounter — not that you will find them in this book.

For Harding sticks, as his subtitle and chapter headings suggest, to the world of publishing. By the 1980s, biographies or memoirs of the rich and famous had become a staple of W&N’s business, bringing in handsome profits. Princess Margaret’s authorized biography became a bestseller, as did Henry Kissinger’s memoir of his White House years. But we also hear about the one that got away, the mega-disaster of Mick Jagger’s ghostwritten autobiography, with its £2 million advance, that didn’t make it into print after being pre-sold worldwide. The manuscript wasn’t fit to publish, said both W&N and the American firm, Bantam. Jagger’s response was: “I just said I can’t be bothered with this, and gave the money back.”

With his reputation badly damaged, it was time, George felt, for New York and Ann Getty, the red-haired wife of Gordon Getty, son of the super-rich Paul. They had met at a dinner party — where else? — and in 1985, after the Jagger debacle, they set up a joint publishing company in New York. But after several years of haemorrhaging money and with no great counterbalancing successes it had to be sold.

With the failure of the New York operation, the finances of W&N hung in the balance. What saved things was its purchase in 1991 by Anthony Cheetham, the founder of Orion Books, with George staying on in the emeritus position of chairman. Now rich and as deeply engaged as ever on the international front, the seventy-two-year-old had no intention of slowing down. Days were packed with meetings, travel and a full social calendar. His own (ghostwritten) autobiography, Remembering My Good Friends, was a flop, but George Weidenfeld sailed on until, towards the end of 2015, his health began to fail. His final illness was mercifully brief. His death the following year brought eulogies from all over the world. “He was the last great example of the vanished world of liberal, cosmopolitan, cultured Europe,” said the Times. More simply, he was a legendary publisher.

This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.