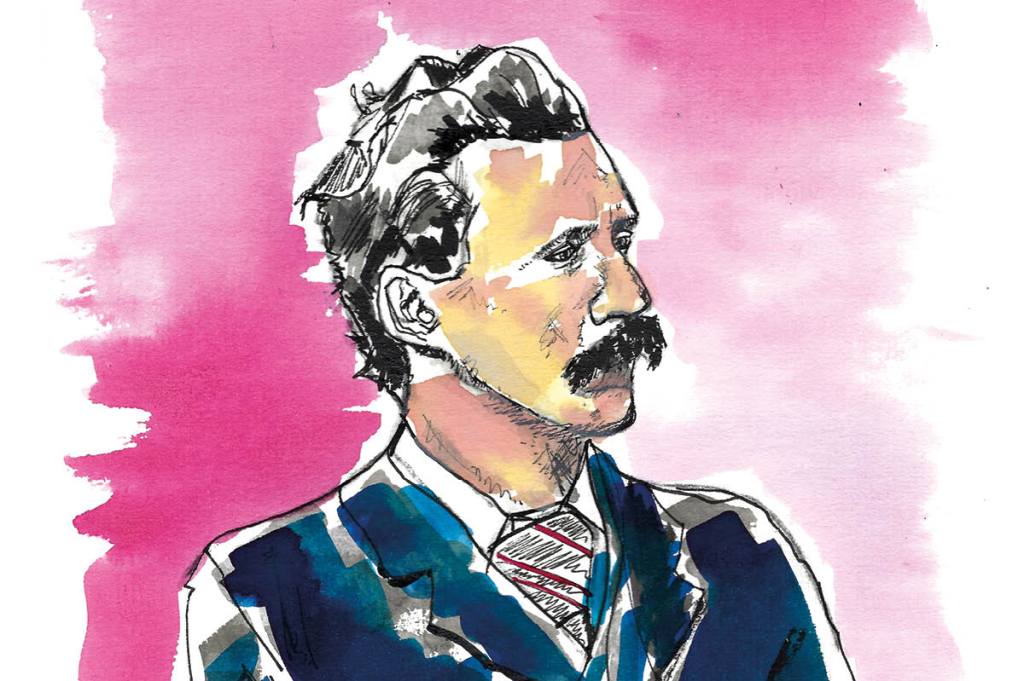

George Gissing died just over 120 years ago, marooned in the French Atlantic resort of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and in circumstances that might have been plundered wholesale from one of his notoriously ground-down novels. H.G. Wells, present at the scene, was so affected by his friend’s deathbed ravings that he transferred them word for word into the mouth of Uncle Ponderevo as he lies dying in Tono-Bungay (1909). There are Orwellian shadings: like Gissing, Orwell died at forty-six of lung disease, and was profoundly influenced by his Victorian forebear. It was Anthony Powell who remarked of Orwell’s third novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936) that “the Gissing had to stop.”

If a small band of enthusiasts has always managed to keep Gissing’s work in print — see, for instance, the Harvester Press reissues of the 1970s and 1980s — then nothing will ever make him popular. The pessimism that infects New Grub Street (1891), A Life’s Morning (1888) or Born in Exile (1892) — the book which can probably be regarded as his masterpiece — is quite unrelieved. You know, almost from the outset, that Godwin Peak, Born in Exile’s embittered hero, will fail to win the girl of his dreams and die in lonely misery, and the novel’s determinism is somehow exacerbated by the feeling of personal hurt that burns off its melancholy pages, the sense of a book that has been built brick by brick out of the wreckage of the writer’s own life.

Godwin Peak, a lower-middle-class intellectual who feigns piety in an attempt to further his matrimonial designs, is not quite Gissing himself, but near enough to him in background and temperament to give the portrait a dreadful sense of conviction. Most of Gissing’s heroes turn out to be trapped in this late-Victorian limbo — educated but hard-up, aspiring but diffident, burning with ambition but darkly aware of their chronic unsuitability for the struggle that lies before them. None of this is calculated to make their lives any easier, and when Gissing observes of Reardon, New Grub Street’s nerve-racked, novel-writing protagonist, that in ideal conditions he could write a tolerably good book every two or three years, you can practically see the workhouse doors opening to receive him.

Most of these anxieties are reflected in the chaos of Gissing’s early life. He was a pharmacist’s son from Wakefield who wrecked a promising academic career by stealing money from his classmates at Owens College, Manchester, with the aim of subsidizing a teenage prostitute he hoped to redeem. The thought that he might have been a distinguished classical scholar continued to haunt him, and the diary that survives his first visit to Greece and Italy in the mid-1890s is written up with a kind of dreamlike fervor. The novels he was forced into writing merely to keep alive tend to fall into two broad categories: they are either savage explorations of the London working-class districts in which he lived as a young man — see in particular The Nether World (1889) — or, as his material prospects improved, more middle-class subject matter. Certainly the author of The Whirlpool (1897) seems at home in a bourgeois drawing room a way that the author of Demos (1885) was not.

What does Gissing write about? Early critics of his work tended to argue that his novels were about women and money. In fact, their true subject is what might be called the emotional consequences of money’s absence. At the heart of his male characters’ discontent is usually their discovery that intellect alone is not enough to win the heart of a respectable middle-class girl. Edwin Reardon in New Grub Street makes the fatal mistake of marrying a socially ambitious woman who imagines she has hitched herself to a genius, and there is a terrible scene in which the novelist, his inspiration and his income gone, reproaches her for her worldliness. Godwin Peak is caught in the same trap, knowing himself to be cut from superior cloth but excluded from the middle-class marriage market by sheer lack of means. Again, their predicaments are Gissing’s own. His two marriages — the first to the prostitute, the second to a woman picked up in the street — were miserable failures, and it was not until the end of his life that he settled down with Gabrielle Fleury, a French admirer who brought some comfort to his final days.

While all this suggests that his novels convey an overwhelming sense of class-consciousness, Gissing’s concept of social distinctions is far from straightforward. He began as a romantic idealist, a worldview encapsulated by the title of his first novel, Workers in the Dawn (1880). On the other hand, any modern reader who examines his mid-period oeuvre is likely to be struck by his almost fanatical hostility to the lower orders. This revulsion reaches its height in the “Io Saturnalia” chapter of The Nether World, which describes August Bank Hol- iday celebrations in a working-class district of London in well-nigh Swiftian terms. Having lived cheek-by-jowl with ordinary Londoners in his youth, Gissing thought them beyond saving, and the atmosphere of his later books is one of straightforward elitism, in which the “gentleman” protagonist is forever trying to detach himself from the mob.

At the same time, despite — or perhaps because of — this prejudice, Gissing is always a reliable observer of working-class street life, and a social historian who wanted to know how a late-Victorian laborer had his hair cut or what he ate for his dinner could do worse than begin with Thyrza (1887), an epic of blighted hopes and frustrated passions set in 1880s Lambeth. And yet his real strength is his grasp of individual motivation. Reardon is said to specialise in “scraps of psychology,” and Gissing, too, has an unflinching eye for the tiny detail that somehow reveals more about his characters’ thought processes than any amount of formal analysis. There is a revealing moment toward the end of New Grub Street in which Reardon’s friend Biffen takes a last look around his garret before setting off to commit suicide and pauses to reposition a book lying upside-down on the shelf.

Something very similar had happened several chapters before, when a battered old literary editor named Alfred Yule, fearful of failing sight, submits to an eye examination by a one-time surgeon met at a late-night coffee stall. The diagnosis of cataract is effectively a death-sentence, but Yule, when volunteering his name, is momentarily lifted by the hope that the man may know of his reputation. In his essay “George Gissing,” published in the Labour magazine Tribune in 1943, Orwell acknowledges this aspect of Gissing’s work and insists that he is a “pure” novelist of a kind that English fiction rarely produces. In this reading, Gissing, with his psychological scraps, his absorption in impulse and personal mythologizing, is much closer to a Russian contemporary like Turgenev than, say, to Dickens or Thackeray.

Certainly Gissing’s naturalism is one of his signatures. He had no religious beliefs, and Born in Exile offers some scathing passages about late-Victorian attempts to reconcile religion with science. In cosmological terms, the average human being is of infinitesimal importance, a kind of lemming clinging briefly to the precipice before a hurricane sweeps in to carry him off to extinction. About the best he can hope for is to suffer as little as possible among tolerable companions. All this might seem to make Gissing first cousin to the great American naturalist novelists of the first half of the twentieth century — to Theodore Dreiser, for example, or James T. Farrell or John Steinbeck, with their bleak dispatches from machine-age Chicago and their suicides quietly expiring in Bowery flophouses.

But Gissing’s naturalism is not Dreiser’s, or Farrell’s or even Steinbeck’s. By and large, their heroes are distinguished by their complete ordinariness, oppressed by vast natural forces they have no way of resisting and scarcely able to understand the environments in which they briefly exist. Studs Lonigan in Farrell’s trilogy is essentially a piece of flotsam, tossed this way and that by contending currents. Clyde Griffiths in Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (1926) is not a tragic hero, one of those Hardyesque exemplars whom the President of the Immortals has singled out for some rough treatment, but an existential fall-guy, a guileless youth who sinks into a pit of his own devising without having the strength to dig himself out.

Gissing’s novels, alternatively, tend to be studies in blighted exceptionalism, chapters in the lives of people born into the wrong world, whose tragedies lie in their inability to find a social or financial position commensurate with their intellectual élan. He is the last great nineteenth-century novelist, a writer whose pessimism is nearly always leavened by an absolute refusal to compromise or otherwise sand down the view he took of the world, a gloomy titan out there on the margins of what he once called “the valley of the shadow of books” — a terrifying phrase that takes you straight to the heart of the kind of person he was and the peculiarly devitalizing conditions in which the business of his life was conducted.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply