The dumbest assertion ever issued in the history of American politics was purportedly uttered by Gary Hart to The New York Times magazine in 1987: ‘Follow me around, I don’t care.’

The Colorado senator, then the front runner for the Democrats’ presidential nomination, was responding to rumors that he was a womanizer. ‘I’m serious. If anybody wants to put a tail on me, go ahead. They’d be very bored.’

What followed, at least in popular memory, became the paradigmatic cautionary tale for American politicians in the age of modern media. The press accepted Hart’s challenge, investigated his personal life, and quickly produced evidence of an extramarital affair: a photo of the senator sitting on a dock with Donna Rice, a much younger woman, straddling his lap.

Hart, humiliated and exposed as a hypocrite, pulled out of the race. Once considered the future of his party, a policy wonk and leading figure among the ‘Atari Democrats,’ (so named for their pro-business, tech-friendly policies), Hart became a punchline, his name forever associated with that of the yacht where his fateful tryst was consummated, Monkey Business.

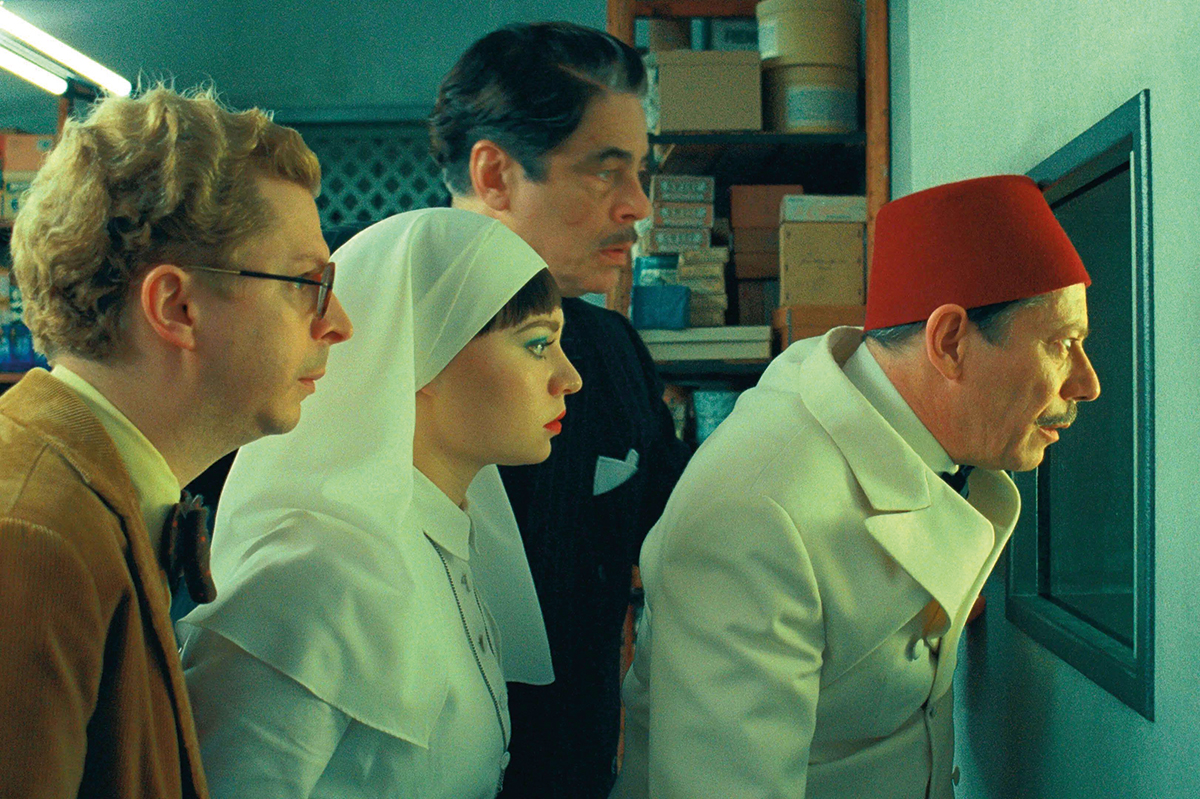

The Front Runner – a dramatization of the scandal starring Hugh Jackman as Hart – depicts this received narrative as mostly wrong. Based on Matt Bai’s All the Truth is Out (2014), the film shatters several common conceptions about Hart’s downfall. The first is that it all came about as the direct consequence of a heedless dare to journalists. Not only was Hart’s comment to the Times made in passing, more importantly, it was published after reporters from the paper that would break the story of his alleged affair – the Miami Herald – had staked out his D.C. townhouse.

The second misconception is, Hart and Donna Rice had a sexual relationship. While the infamous photograph and unfortunately-named boat might suggest so, both parties denied it. Only circumstantial evidence suggests otherwise.

And finally, that Monkey Business photo, still the first image to appear when you Google ‘Gary Hart.’ It wasn’t published until after Hart dropped out of the race.

The Front Runner doesn’t just revise our perception of the events that crushed Hart’s political fortunes. It also challenges our understanding of a man mostly remembered for supposed arrogance and hypocrisy. Director Jason Reitman portrays Hart sympathetically, as the first politician to have his reputation destroyed and his career ruined by a mainstream media which embraced tabloid values and never looked back. Whatever you think of Hart’s politics — and Reitman clearly thinks he was the best president American never had — the precedent of Hart’s undoing has dissuaded countless people from entering public service.

From All the President’s Men and The Killing Fields to Network, Spotlight, The Post, and the newly released A Private War, Hollywood loves to glamorize journalists. This passion has become more prominent in the age of Donald Trump, with journalists behaving like only they can save the world from our reality TV president, and he, in a vicious circle, encouraging their insufferable piety by obnoxiously decrying them as ‘enemies of the people.’

What makes The Front Runner, set three decades ago, so novel and refreshing is that journalists are its unmitigated villains. When one of the Miami Herald reporters righteously declared ‘It’s up to us to hold these guys accountable!’, my fellow audience members snickered in disgust. Seeing our intrepid hacks cornering an agitated Hart in the alleyway behind his Georgetown home and peppering him with questions about his sex life has the opposite effect of watching Bob Woodward meeting Deep Throat in a parking garage. The Post reporter was legitimately trying to save American democracy from a criminal president. This encounter has all the import of a Jerry Springer smack-down.

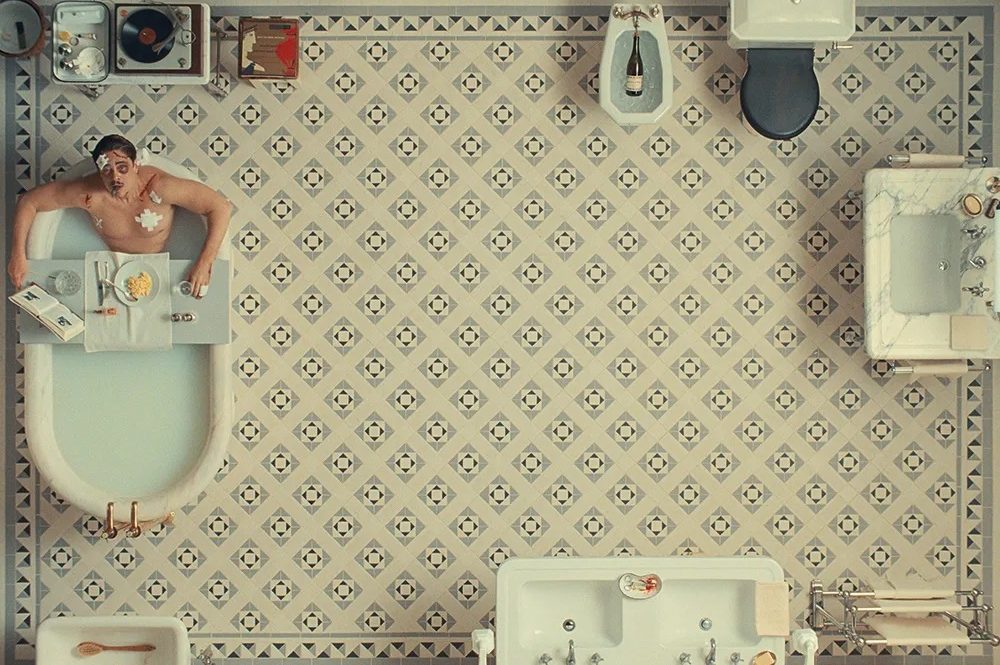

I haven’t seen a more cynical cinematic portrayal of journalistic monkey business since Volker Schlöndorff’s The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975). In Schlöndorff’s film, a reporter for a right-wing tabloid (explicitly based on the German daily Bild) ruthlessly harasses and slanders a naive young woman whose crime is to have spent the night with a man whom, unbeknownst to her, is wanted by the authorities on terrorism charges. The acts of sadism inflicted upon Ms Blum by actor Dieter Laser would only be surpassed by those he later meted out to a pair of hapless young tourists as the depraved doctor in The Human Centipede (2009). But enough about American journalism.

The Front Runner makes a welcome, if futile, call for rescuing our politics from tabloid trivialities. When a female Post reporter justifies scrutiny of Hart’s personal life on feminist grounds, it feels like overcompensation by screenwriters wary of #MeToo sensibilities. Ultimately, partisanship rules the day.

Critiques of media bottom-feeding are loudest when the victims are hangdog Democrats like Gary Hart and Bill Clinton. Consider the crowd-sourced McCarthyism against Brett Kavanaugh, in which the Times reported in all seriousness that the future Supreme Court judge had thrown ice at someone while a student at Yale. Liberals can be just as puritanical as their conservative adversaries.

These ironies are unlikely to register with many of those who will applaud this film. They may decry the shoddy treatment of Gary Hart, but they’ve spent the past year breathlessly poring over every lurid detail of the president’s monkey business with a porn star.

James Kirchick, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, is writing a history of gay Washington, D.C.