‘It’s a beautiful world if it wasn’t for Gandhi who is really a perfect nuisance,’ Lord Willingdon, Viceroy of India, wrote in 1933. Gandhi would have been 150 years old in 2019, had he taken better care of himself. He remains the most irritating and admired politician of the 20th century: a perfect subverter of power and political logic, but a nuisance to everyone, allies included. Only Hitler, the other anti-capitalist spiritual politician who broke the British Empire, fascinates to the same degree.

The first volume of Ramachandra Guha’s biography, Gandhi Before India (2013), carried the young Gandhi across the British Empire from Kathiawar to London to Cape Town. In South Africa, Gandhi developed a one-two tactic of Thoreau-style passive resistance and Whiggish appeals to the law, and reconciled these secular western influences with Hindu precedents as ahimsa, ‘non-violence’, and satyagraha, ‘truth force’. This volume resumes in July 1914, with Gandhi taking ship from Cape Town for London and then Bombay, and preparing to reconcile India to himself. Like Guha’s first volume, it humanises the saint and illuminates the times.

Gandhi wanted to replicate his South African success in India by massing Hindus through appeals to tradition, and welding Muslims into this Hindu-majority cause. The stumbling blocks arose within days. A ‘political and social outsider’, Gandhi relied upon his ‘guru’ Gopal Gokhale for orientation, and entered Hindu politics as a moderate who defended the caste system while criticising its degradation of the Untouchables. On his fourth day back in India, Gandhi met Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a Shia lawyer active in the Muslim League.

It is a testament to Gandhi’s political abilities that by 1920 he was leading the Indian National Congress, and his tactic of mass ‘non co-operation’ had become a human lever for displacing the Raj from India. Gandhi had realised in 1908 what the Japanese would demonstrate in 1941: British power in Asia was a paper tiger. If the Raj ruled with the consent of the governors, the native kings and princes, it could be overthrown by raising the governed against this alliance. Any other empire would have hanged him. Instead, the British helped him, shamed before their own laws as by the Rowlatt Act, the slaughter at Amritsar and the moral crime of the Salt Tax.

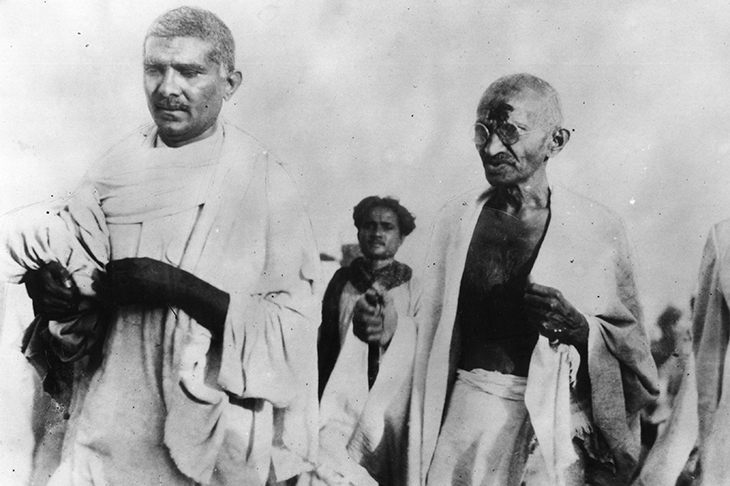

‘I realised what a consummate artist-realist the old man must be,’ an eye-witness wrote after seeing Gandhi striding forward on the Salt March in April 1930. ‘The breathless walk made you see how urgent and downright and final was his call and message.’ Three months after the Salt March, the Labour-led British government invited the Indian factions to negotiate India’s transition to Dominion status. Gandhi boycotted the Round Table talks, but attended a second round after establishing himself as the Congress party’s sole representative. Unwilling to compromise on anything less than full independence, he resigned as INC leader in 1934.

Guha does not consider the resemblance between Gandhi’s image-consciousness, his feeding of his fame by starving himself for the cameras, and the media strategies of the other 1930s demagogues. Intellectually, Gandhi was a child of late-19th century Lebensreform. His prose style and wearingly cheeky persona are George Bernard Shaw with the Jaeger suit and bicycle swapped for a dhoti and a hand loom. His politics were a spiritual and personal cure; their translation into communal strategies and geopolitics intensified the ailment. In 1948, he was killed by the religious furies he had invoked.

Guha describes Gandhi’s sadism towards his children and wife Kasturba; his opposition to contraception; his manipulation of the Muslims and ‘patronising’ of the Untouchables; his ‘naïveté’ about non-violence as a tactic against dictators, and his ‘ill-judged’ and ‘poorly timed’ statement of May 1940: ‘I do not believe Herr Hitler to be as bad as he is portrayed.’ We also hear about his launching of the Quit India campaign in 1942, when only the British could have stopped the Japanese from turning India into a slave plantation; and his ‘bizarre’ experiments in sleeping naked with his granddaughter and his grand-nephew’s wife, about which Guha, producing new evidence, suggests that ‘there may have been, as it were, two sides to the story’.

Other people paid the price of Gandhi’s sanctity. Orwell, unimpressed, noted ‘how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind’, compared to ‘the other leading political figures of our time’. Guha is not taken in by Gandhi’s odour of sanctity, though he is more than sympathetic to the motives of its production. He is as fair as an admirer can be. Regardless of Gandhi’s squalid vanities, there is still much to admire about him. Like Churchill, he was wrong about most things but right about the most important one. Ageing fornicators will be amused to read that Gandhi ‘gave up sex in his thirties’, when he was still ‘fully capable of enjoying its pleasures’.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.