In 1928, a modest young lecturer from Milwaukee, Mildred Harnack, née Fish, arrived in Berlin to begin her PhD in American Literature. In the febrile, polyglot atmosphere in the city at the ‘crossroads of Europe’, the media was still mocking Adolf Hitler and few took him seriously. Mildred saw, close up, the brokenness of American and German capitalism and, distantly, the apparently level playing fields of communist Russia. As the Nazis gained increasing control over the body politic, she taught an overtly socialist syllabus — Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser et al. When, halfway through her dissertation, the university fired her, she promptly started teaching at a night school for working-class students. ‘Should Hitler be chancellor?’ she asked her pupils.

Within six months the country had become a dictatorship. Newspapers were closed, political opponents were taken into ‘protective custody’ and camps were built. ‘The situation grows steadily worse,’ Mildred wrote to her uncomprehending mother back in Wisconsin: ‘We must change it as soon as possible.’ She and her friends began convening a regular ‘discussion circle’ (or Kreis) in her apartment, composed of students, aristocrats, bohemians and even a former member of the Hitler Youth.

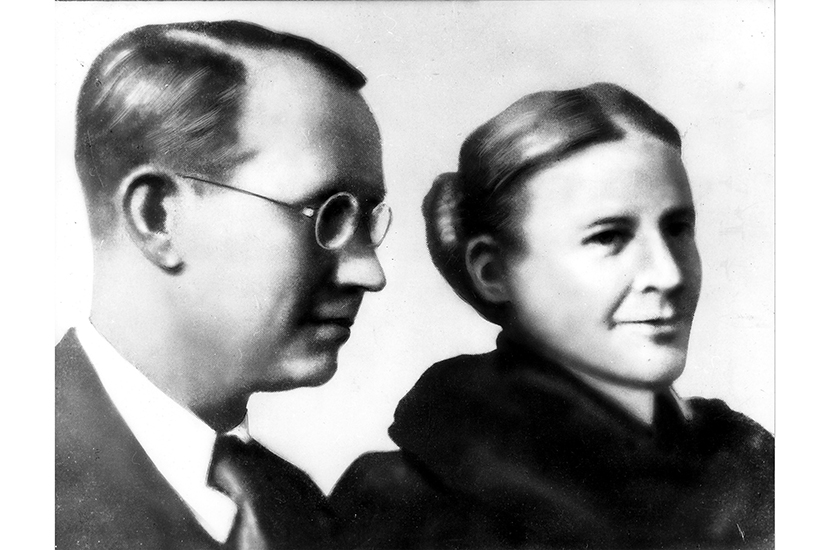

Two years earlier, in America, she had married the equally earnest Arvid Harnack (they’d honeymooned on a picket line in Colorado). He was a German economist with a fondness for the Soviet model and a cousin of the Bonhoeffers, one of whom, on the couple’s arrival in Germany, got him a job first at Lufthansa, then at the ministry of economics, where he reported directly to Hjalmar Schacht. He began urgently leaking evidence of Germany’s war preparations. Mildred, meanwhile, took advantage of her friendship with the US ambassador’s giddy daughter, Martha Dodd, to gain access to sympathetic American officials and high-ranking guests at embassy parties.

The Kreis stole documents, printed and distributed leaflets, helped Jews escape through consular contacts, translated and smuggled foreign speeches into German factories and government departments (including Goebbels’s propaganda ministry), exposed war-profiteering and German atrocities in uniform, and attempted to give crucial economic and military intelligence to the soon-to-be Allies. The tragedy was that it was all for nothing. The western Allies persisted in dismissing the idea of any German resistance movement, and Stalin, despite countless warnings, continued to stare into the funfair mirror of his paranoia until the morning after Barbarossa.

At the time of Mildred’s arrest in December 1942 she was teaching English to the SS while belonging to one of the largest anti-Nazi resistance groups in Germany — a chaotic mix of socialites, diplomats, officials, military officers, broadcasters, engineers, socialist literati, spies and a journalist turned ‘fortune teller’, who used her sessions with German soldiers to extract strategic information. Thanks to Arvid’s formal, if reluctant, conversion to paid espionage, Mildred was also very actually in bed with Soviet interests.

It was the Russian connection which did for the couple. In ‘one of the most significant espionage blunders of the second world war’, a callow NKVD chief sent a telegram which included Mildred’s name and address undisguised. The Abwehr dropped the net, and one fish gave up most of the others.

Arvid received the death sentence. Mildred, extraordinarily, was given only six years’ hard labor — until Hitler personally intervened. She spent her final days in solitary confinement, translating Goethe — hence the book’s title. On February 16, 1943, aged 40, she was guillotined in Plötzensee prison.

The job of bringing this courageous woman back to life has fallen to her great-great niece Rebecca Donner. She acknowledges the difficulty of writing about someone whose aim, by virtue of her work, was ‘self-erasure’. I’m not convinced that the book lands its stated claim — that Mildred was at the ‘heart of the resistance movement’. And the material feels a little stretched between her arrest and events such as Operation Valkyrie towards the war’s end.

But the pacy present-tense narrative, assembled from testimonials, memoirs and diaries, disguises many of the cracks. We learn of details such as the Moscow import-export front called ‘Foreign Excellent Trench Coats’, and of the hideously creepy questionnaire Mildred was presented with on the day she died: ‘Do you have especially strong passions? (Drinking, smoking, sexual excess?)’ The group’s mug shots are terrible in their banal officialdom. Altogether, it’s an impressive piecing together of fragments.

‘The archives tell us a great deal,’ writes Donner, but ‘much is missing from them.’ Now, at least, All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days stands as a memorial to Mildred Harnack. As one of her interrogators said of her story: ‘It would make a wonderful novel if it weren’t so sad.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.