“I don’t know how many times in nearly forty years I have come back to this novel,” Graham Greene said of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, published shortly after the outbreak of the First World War. The fiction of both English authors — both converts to Catholicism — share a deep cynicism towards modernity and a depiction of the English establishment as decadent and in decline.

The Good Soldier, whose original title The Saddest Story was canned by the publisher because it would render the book “unsaleable” during World War I, tells the tale of two married couples, one British (British Army Captain Edward Ashburnham and his wife Leonora) and the other American (John and Florence Dowell). Both pairs are, on the face of it, young, prosperous, and happy. Captain Ashburnham, a paragon of Edwardian elite sensibilities, seems especially admirable: a holder of both the Distinguished Service Order and the Royal Humane Society’s medal; twice recommended for the Victoria Cross. He is tall, handsome, and blonde, and an inheritor of a great English estate, Bramshaw Teleragh.

Nevertheless, observes David Bradshaw in the introduction of the book’s Penguin edition, “If there is one mood which dominates the novel, it is doubt.” The four meet at a spa in Nauheim, Germany, where Edward and Florence are ostensibly receiving treatment for heart ailments. There is, however, a superficiality to their friendship and vision of the good life. John Dowell, the narrator, explains, “What characterized our relationship was an atmosphere of taking everything for granted… We took for granted that we all liked beef underdone but not too underdone; that both men preferred a good liquor brandy after lunch; that both women drank a very light Rhine wine qualified with a Fachingen water — that sort of thing.”

Neither couple is actually happy. Unbeknownst to Dowell, his wife has been cheating on him since the beginning of their marriage, first with a “lugubrious, silent, morose” painter named Jimmy, and later, as the couples’ friendship progresses, with Edward Ashburnham. The English officer, in turn, has a long list of liaisons, including not only Florence, but a Spanish dancer, a young married woman, and eventually his own ward. For years, Ashburnham pays a blackmailer 300 pounds a year to keep one of his affairs hidden.

Edward and Florence’s tryst comes to light when the couples visit an ancient German city that’s home to various artifacts from the Reformation, including a piece of paper in a glass case signed by prominent first-generation Protestant Reformers. “There it is — the Protest,” Florence exclaims with awe. “Don’t you know that is why we were all called Protestants?” She continues with a flourish that showcases the depths of her hypocrisy: “It’s because of that piece of paper that you’re honest, sober, industrious, provident, and clean-lived.” She then lays a finger on Ashburnham’s wrist, unintentionally revealing to Leonora their shared romantic affections. The irony is made thicker by the fact that Leonora is not a Protestant, but an Irish Catholic.

The incongruity of that scene is heightened by Dowell’s reflections on the two couples’ frustration with their culture’s mores regarding sex. “And there is nothing to guide us,” he writes. “And if everything is so nebulous about a matter so elementary as the morals of sex, what is there to guide us in the more subtle morality of all other personal contacts, associations, and activities? Or are we meant to act on impulse alone? It is all a darkness.”

That cynicism and nihilism is further accentuated given the couples’ enjoyment of comfort and ease during almost a decade wandering Europe together. “But upon my word, I don’t know how we put in our time,” Dowell muses. “How does one put in one’s time? How is it possible to have achieved nine years and to have nothing whatever to show for it? Nothing whatever, you understand.” Given more freedom to explore and opportunities to excel than practically any generation in human history, these early twentieth-century English aristocrats drown themselves in fleeting amusements, liquor, and sexual liaisons.

“Why can’t people have what they want?” Dowell demands to know. Demonstrating a lack of self-awareness common to the wealthy, he contemplates what seems to him a contradiction: “The things were all there to content everybody; yet everybody has the wrong thing. Perhaps you can make head or tail of it; it is beyond me… Are all men’s lives like the lives of us good people … broken, tumultuous, agonized, and unromantic lives, periods punctuated by screams, by imbecilities, by deaths, by agonies? Who the devil knows?” Yet who’s to say Ashburnham and Florence would have remained happy?

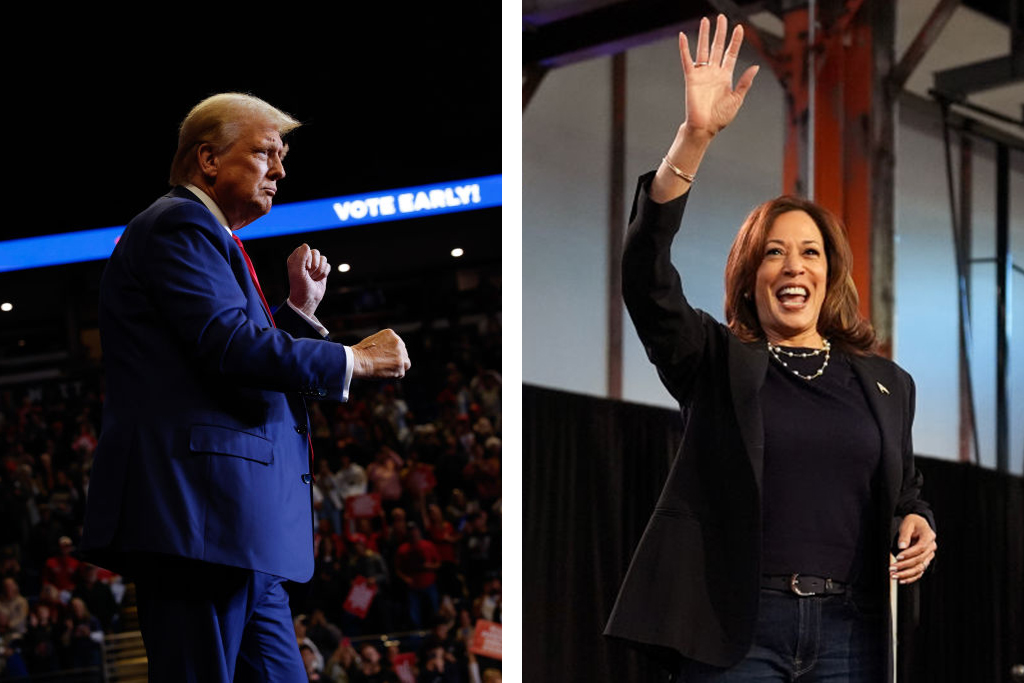

We in the twenty-first century, in which divorce is no longer shameful, should be seasoned enough to know the answer. Having betrayed one romantic commitment, and suffering little if any societal consequences, why should we not do it again? The divorce rates for second and third marriages are even higher than those for first marriages. Does anyone really think Kim Kardashian, who just divorced her third husband, is happy?

“You may well ask why I write,” Dowell says to the reader. “And yet my reasons are quite many. For it is not unusual in human beings who have witnessed the sack of a city or the falling to pieces of a people to desire to set down what they have witnessed for the benefit of unknown heirs or of generations infinitely remote.” Like Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher, The Good Soldier foreshadows a larger collapse, that of the WASP elite, who over the course of the twentieth century forfeited their virtue, nobility, and wealth in pursuit of a narcissistic hedonism. Inheritances were squandered, churches emptied, family lines ended.

“And they themselves steadily deteriorated,” observes a befuddled Dowell, considering the fate of Ashburnham and Florence. “And why? For what purpose? To point what lesson? It is all a darkness.” No longer tethered to religion or even a sense of transcendent purpose, prioritizing their own affectations over duty to their family or society, the WASP elite, ridden with doubt, struggle to find a reason to persevere. “So life peters out,” Ford’s protagonist notes.

“Well, this is the saddest story,” remarks Dowell. For what the WASPs once were, and what of their wonderful cultural inheritances survive to be bequeathed to us, I’m inclined to agree.