On May 6, 2010 the eurozone crisis was tearing through the continent. Greece was bankrupt, and it looked as though Spain or Italy could be next. Markets were on edge, volatility was high — and then something very strange happened.

The S&P 500, one of the US’s main stock indexes, began to crash. It went faster and further than it ever had before, losing 5 percent of its value in four minutes. The shock spread to the Dow Jones, which hurtled downwards. Financial markets across the globe were going haywire. The oil price started to fall. Shares formerly valued at $50 were suddenly trading at 0.0001 cents while others soared. In little more than 20 minutes, trillions of dollars had been wiped off the value of global markets. But then, quite suddenly, normality returned and prices went back to normal. It came to be known as ‘the Flash Crash’. But what had happened? Who was responsible?

The culprit wasn’t a hedge fund manager or Wall Street CEO. Navinder Sarao couldn’t have been further from the world of high finance if he’d tried. Nav, as his friends called him, had no office in Mayfair. Instead, he traded from his bedroom at his parents’ house in Hounslow. The officer who eventually arrested him described the room as ‘musty and unkempt’. There was a single bed, a labrador-sized stuffed tiger and on the wall a framed pair of football boots, signed ‘To Nav, from Lionel Messi’. At the end of the bed was the scene of the crime: ‘a desktop with three screens connected to a standard broadband line. And that was it.’ As far as the authorities were concerned, Nav had caused the Flash Crash and he’d done it all from his bedroom.

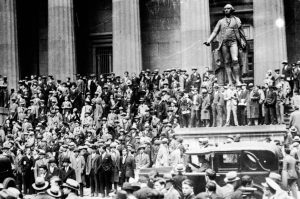

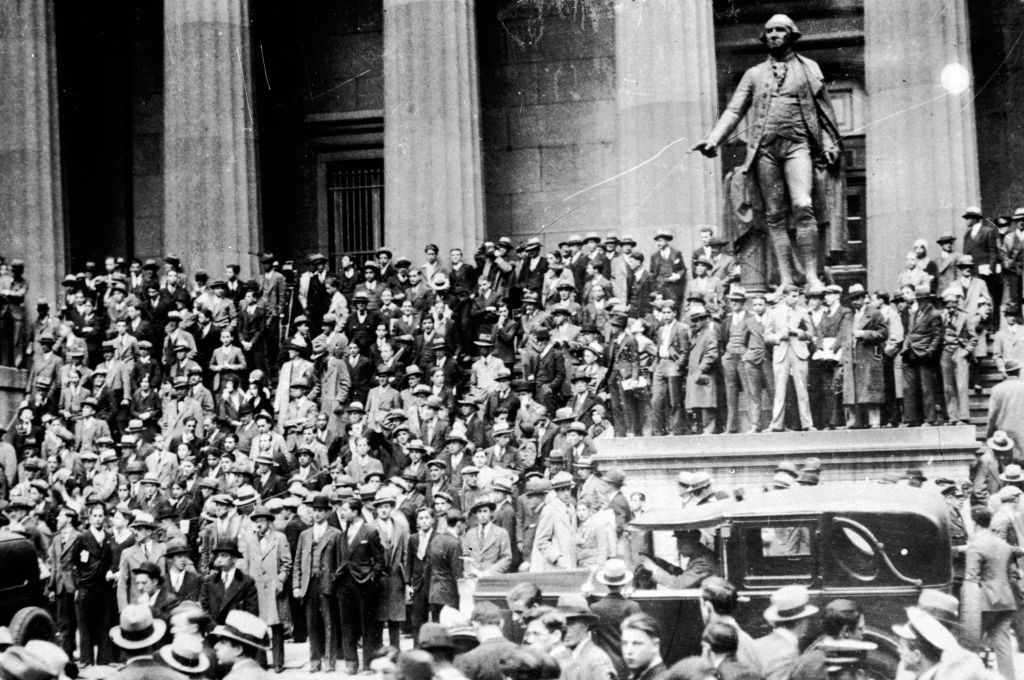

Financial markets are not what most people think. Forget about Trading Places and the exchange floors crammed with buyers and sellers. All that went out decades ago. Now it’s all done by computer, meaning that anybody with a connection and some money behind them can, in theory, play the global markets.

That’s just what Nav did. In 1998, he left university and eventually joined a futures trading firm based in Woking, Surrey. It turned out he was rather gifted. Over his first four years, he banked $400,000, and it got to the point where he was making $20,000-$25,000 a day. After a disagreement, he left the firm to go solo, working alternately at a rented office and from his parents’ house. His revenues soared. In November 2008 alone, he made $15 million on the futures market.

One of the strategies he used was ‘spoofing’. That’s where a trader places a large batch of orders to buy a particular futures contract, which creates the impression that demand for that asset is increasing. Other traders see this change in demand and begin to buy, which causes the price to tick upwards. The ‘spoofing’ trader, having made the market move in the direction he wanted, quickly cancels his original batch of orders — they were just a decoy — and then carries out the transactions he intended all along. That’s what Nav was doing and it was making him a fortune. Unfortunately it was completely illegal.

The target of Nav’s spoofs and the object of his professional frustration, were the High Frequency Traders (HFTs). These are firms that use super-high-speed computer programs to carry out their transactions. They also have agreements with exchanges to gain access to market information fractions of a second before everyone else. These advantages allow HFTs to exploit market information that is available only to them, which can yield colossal financial rewards. Nav saw this as nothing other than cheating. The big, wealthy traders were using their political connections and technological advantages to stuff everyone else. He wanted to get back at them.

So he built his own bespoke ‘spoofing machine’, a trading algorithm specifically designed to fool the HFTs — and it was ‘wildly, scarily effective’. On one occasion he turned on his spoofing machine for just a few hours and made $435,185. On another day he made $876,823. Having tweaked the algorithm again, in the summer of 2012 Nav was able to make $55,000 per minute, the program placing and then canceling almost unimaginable numbers of spoof offers. When the US regulators later recreated Nav’s trading activities they found that over a 12-day period his algorithm had placed or cancelled orders with a notional value of $35 trillion.

It was inevitable that activity on this scale would be noticed. A junior employee at a Chicago trading house who happened to be sifting data from the day of the Flash Crash spotted the patterns left behind by Nav’s trades. His digital fingerprints were everywhere. Eventually the FBI, along with the Met, arrived at the Sarao family home in Hounslow.

The US prosecutors put up such a terrifying array of charges against him that Nav was forced to enter into a plea bargain. After a spell in prison and some cooperation with the authorities, the judge took pity and he got off lightly. His punishment was one year’s confinement to his parents’ house and a lifetime ban from the markets.

***

Get three months of The Spectator for just $9.99 — plus a Spectator Parker pen

***

But had he actually caused the Flash Crash? The press jumped on the idea that he had — but Liam Vaughan is less convinced. A further question raised by the book is whether Nav had really done anything wrong. When the US investigators interviewed executives from HFT firms, they began to have their doubts:

‘After meeting a particularly obnoxious young multimillionaire, who greeted them in his palatial, high-rise office wearing flip-flops and a Hawaiian shirt, one investigator joked: “So, these are our victims?”’

It’s an extremely well-researched and clearly written book. It is also a reminder of the sheer oddity of the world of cutting-edge finance, in which very rich, clever people spend their professional lives selling each other bits of data. Navinder Sarao wanted to break into that set, and in doing so he disrupted some of the biggest, wealthiest and best politically connected financiers in the world, some of whom he regarded as cheats. Whether he and his spoofing machine caused the Flash Crash will always be unknown, but one thing’s for certain: he out-cheated the cheats. By the end of this story you can’t help but admire him for it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.