That creaking sound you hear creaking is Jack Warner, the founder of Warner Bros. studio, turning in his grave. Last week, it was announced that Netflix had purchased one of Hollywood’s most respected studios for a staggering, indeed insane $83 billion – which makes Disney’s purchase of Lucasfilm for $4 billion in 2012 seem like the bargain of the century. The sale would create a monopoly the likes of which has never been seen before in the film industry.

Most people assumed that such a bid – in this increasingly beleaguered business – is very, very bad news. They might be correct. That’s why it’s even more staggering that Paramount have today, with impeccable timing, announced their own hostile takeover bid for Warner, offering an even more outlandish $108.4 billion and asking its shareholders to reject the Netflix dollar in favor of a deal that values its shares at $30 each.

Paramount, which has offered repeatedly to buy Warner but been rebuffed six times in the past 12 weeks, has shown its teeth in no uncertain terms. CEO and chairman David Ellison announced that it was suggesting a “strategically and financially compelling offer to WBD shareholders” and that “WBD shareholders deserve an opportunity to consider our superior all-cash offer for their shares in the entire company.” For good measure, Ellison called it “superior value, and a more certain and quicker path to completion.” In other words, a very, very wealthy man is set on acquiring Warner, and not even the Netflix deal – which was looking all but a fait accompli last week – will stop him.

Anyone who knows the slightest thing about cinema will recognize that three very different games are in play here. Warner has traditionally had a reputation as “the directors’ studio,” working closely with auteurs such as Kubrick, Eastwood, Nolan – until they screwed up the release of Tenet and he fled to the loving arms of Universal – and, more recently, Greta Gerwig. Netflix has a similar reputation for working with auteurs (Scorsese, Fincher, Bigelow and Guillermo del Toro have enthusiastically taken their dollar), but they are – shall we say – less than committed to the theatrical experience. And Paramount have just wrapped up their Mission: Impossible series with Tom Cruise – the latter two films of which underperformed financially – and their biggest franchises are Sonic the Hedgehog, A Quiet Place and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Auteurs are not to be found on their lot.

Warner has been having a vintage year, notwithstanding the departure of Nolan. Under the inspirational guidance of Michael De Luca and Pamela Abdy, the studio has produced hit after hit, making every other Hollywood institution look uninspired and tame, and this has been recognized accordingly with the Golden Globes nominations. The genius of it is that they’ve put out everything from the likely Oscar front-runners One Battle After Another and Sinners to the squillion-grossing likes of Minecraft and Weapons. No other studio currently rivals Warner for creativity, verve and, indeed, financial success. Lest we forget F1, which they distributed, was a mega hit off the back of Brad Pitt’s charisma and an iconic Hans Zimmer score. Their absorption into either the Netflix or Paramount fold cannot, in all honesty, be seen as a good thing.

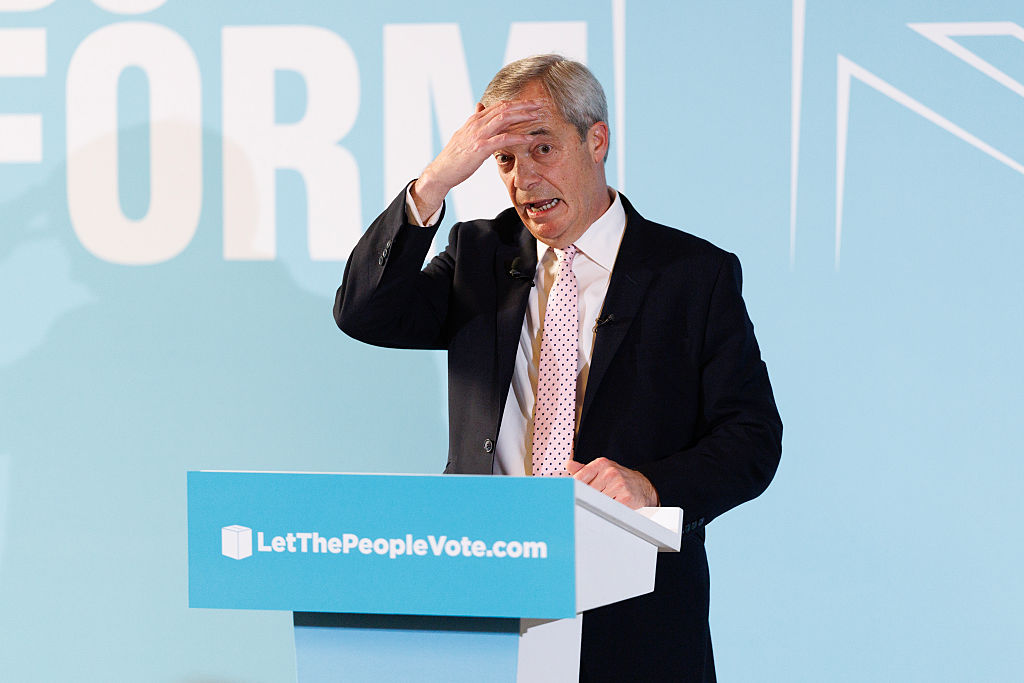

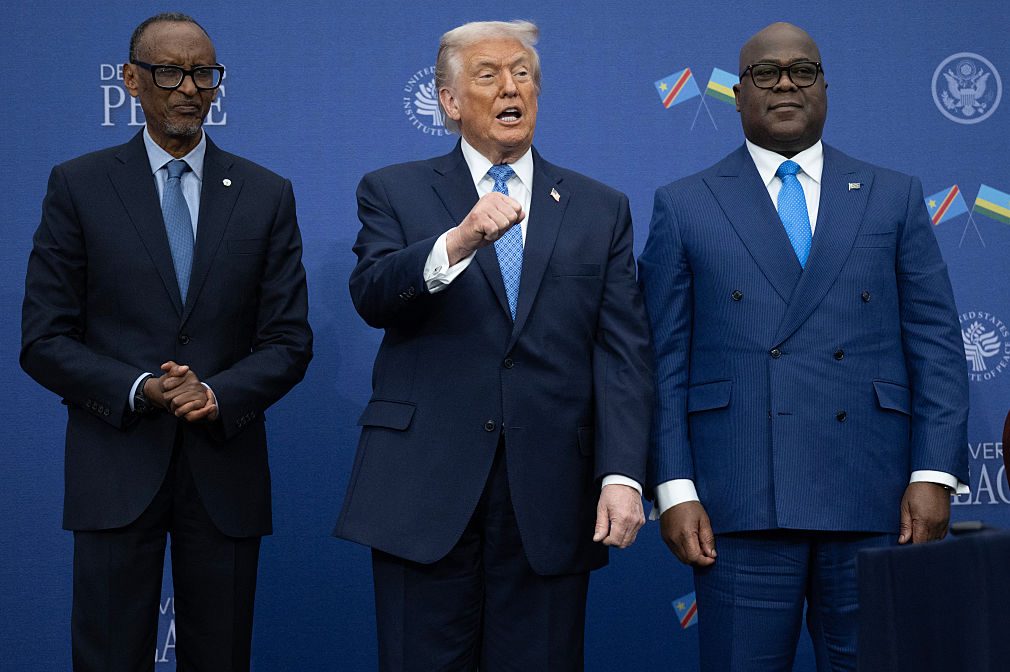

What is likely to happen? President Trump suggested last weekend that a Netflix-Warner acquisition “could be a problem” because of market share laws, and so Ellison’s offer, which was not entirely unexpected save in its enormity, might appear to circumvent this, much as Disney’s purchase of Fox (for a mere $71.3 billion) has established similar precedent. Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos, a man who thinks you can and should watch Lawrence of Arabia on an iPhone, will be furious – and it’s not impossible that he will counter with a yet-higher offer.

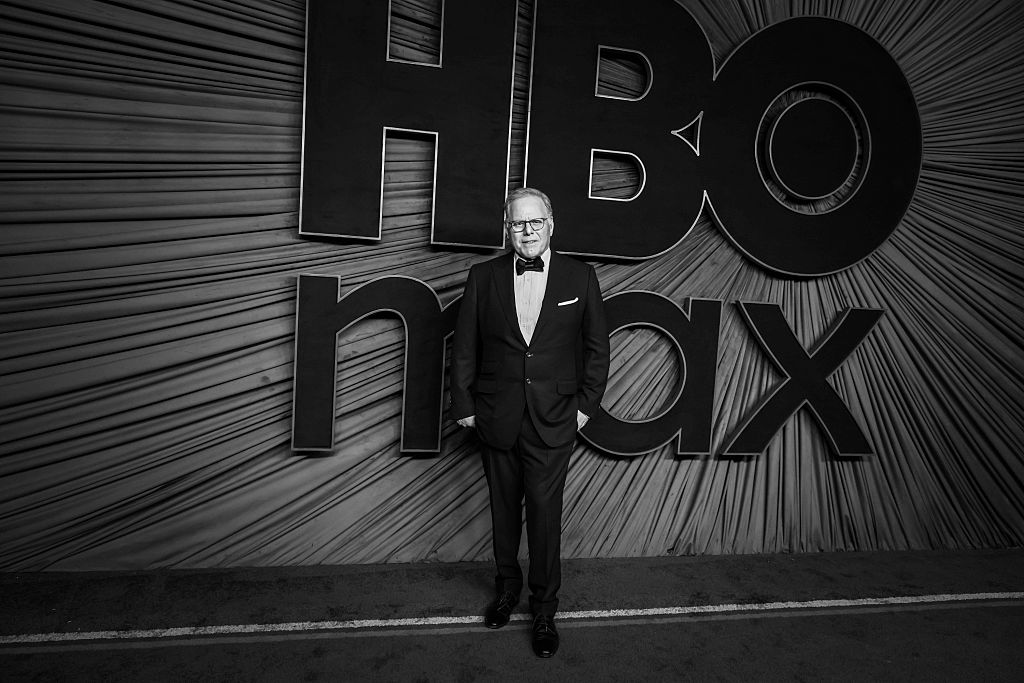

None of this is especially good for cinemagoers. De Luca and Abdy may be visionaries, but the studio is still under the control of David Zaslav, an uninspired bean-counter if ever there was one. In The Studio, the Seth Rogen Hollywood satire, one of the central jokes was that the eponymous institution is desperate to make a film based on the Kool-Aid man. At this rate, whoever ends up buying Warner will have drunk the Kool-Aid in no uncertain terms and will want a return on their investment. Cinema, in its most fragile state imaginable, will only suffer as a result of this dick-swinging – and Jack Warner’s ghost must be tormented by what it is witnessing happen to his pride and joy.

Leave a Reply