My first novel, A Dog’s Life, was largely autobiographical. It described my grandparents’ life, my parents’ marital exploits, and my own limping attempts to become a writer. But since I seemed unable to harness these first two subjects to the advancement of the third. Then I suddenly saw how I might carve out the first quarter of this spacious family saga and make it a self-contained novella covering 24 hours of family life.

Heinemann offered me an advance on royalties of £500, which was ten times what they had given me for my biography of Lytton Strachey. Roland Gant did not wish to publish A Dog’s Life until the two Strachey volumes were out of the way. But since Penguin wanted the novel as a paperback and my publisher in the United States also sent me a contract, I was happy.

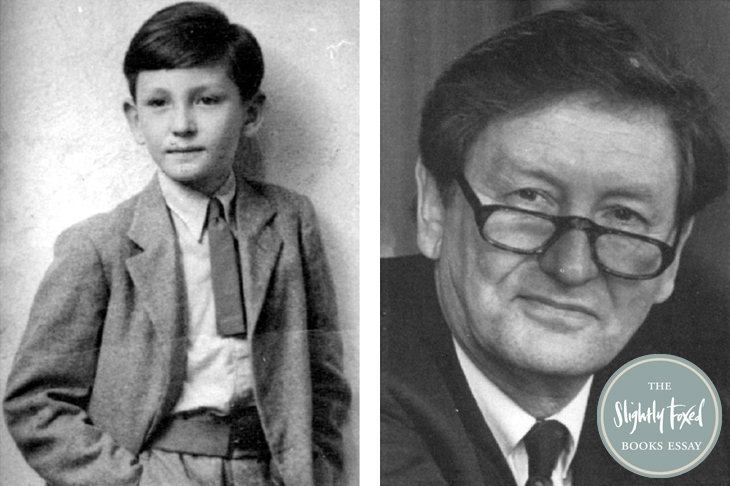

My father was not happy. He had given up writing novels by then, and assumed that I had done so too. He had read an early draft of my novel guardedly, reassuring himself perhaps that it would never be published. When I posted him the later shortened typescript, his reaction was more sparing in its praise than Roland Gant’s.

‘The typescript of your book arrived,’ he wrote, ‘and I read two or three chapters before I was so nauseated that I had to put it down.’

Since the first two chapters covered five pages and the third chapter reached the top of page eight, this was not encouraging. He wanted to impress on me as dramatically as possible how dreadful my novel was. When I urged him to complete it (it was not long), arguing that the death of Smith, the family dog, brought out the underlying sympathy of the characters (a sympathy sunk so deep, one reader was to write, that you needed a diver’s suit to reach it), he simply refused. He hated everything about it.

‘Your formula is evident. Take the weakest side of each character – the skeleton in every cupboard – and magnify them out of proportion so that they appear to become the whole and not part of the picture . . . Surely you could have written a study of old age and loneliness without photographing your own family for the background? Why should they be pilloried? You go out of your way to avoid any redeeming features in anyone’s character. One would have thought that you could have waited a few years until we were dead before appraising the world of our misery.’

If I went ahead and tried to publish the novel, my father promised to bring legal proceedings against me and the publishers. Publication would, he believed, expose to savage ridicule the whole family.

‘As you know I work in a firm with a staff of several hundreds…In the circumstances – for my sister’s sake and my own – I must do everything to prevent this book being published anywhere till we are dead, and I am prepared to take whatever steps that are necessary legal or otherwise.’