In 1920 Warren G. Harding was elected president of the United States, after campaigning on a promise to the American electorate to return the country to what he called “normalcy.” Exactly one hundred years later, Joe Biden assumed the same office having offered the same thing, in different language. In July 1922 Sinclair Lewis published Babbitt, a bestselling novel about a normal middle-class American businessman living in a normal small-sized Midwestern city: the quintessential personification of “normalcy.”

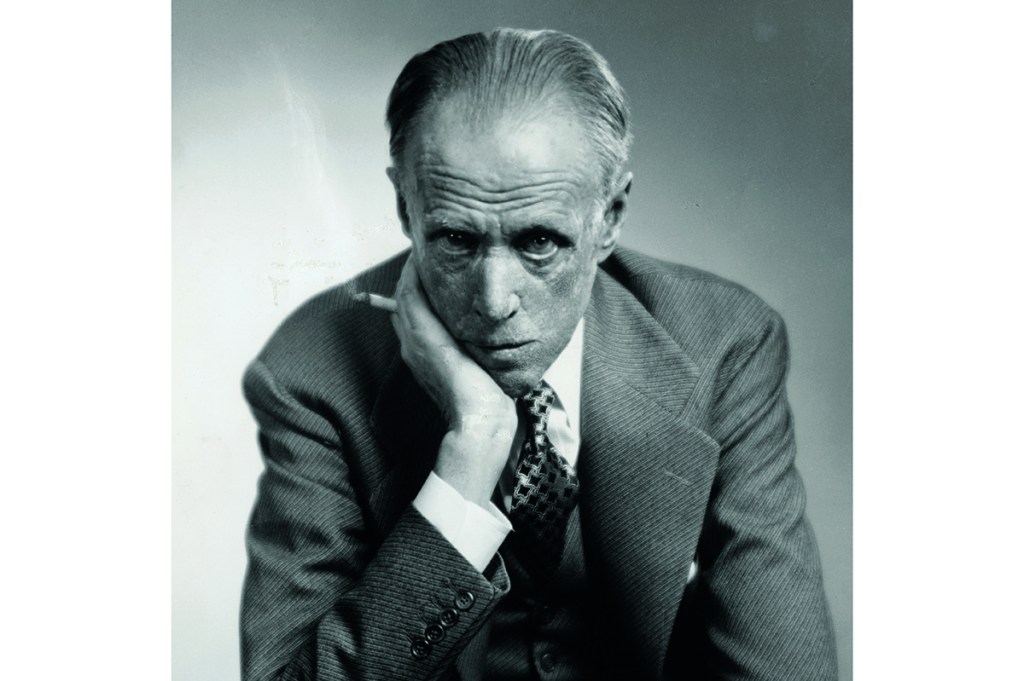

Around the middle of the same decade, H.L. Mencken, a good (if necessarily patient) friend of Lewis’s, predicted that America would “blow up” in a hundred years. 2022 is Babbitt’s centennial year. It seems appropriate to speculate about how the novel would read had it been written a century later, and how life in the United States has changed over the ten intervening decades.

The country as Lewis described it remains wholly recognizable today. By the beginning of the first decade following the Great War, all the major institutions on which twentieth-century American was subsequently built had been established: the automobile culture, suburbia, widespread industrial production, the new advertising industry, mass communications and popular culture were already firmly in place.

There are obvious reasons for this. Babbitt’s beloved Zenith — Lewis had Cincinnati in mind as his model — is a relatively small American city, belonging to the social category that has been least affected over the past century in which rural communities have emptied out and dried up, major metropolises have been wracked by crime and suburbia has exponentially expanded, demographically and geographically, to become the American social norm.

Babbitt’s circle of social acquaintances is equally recognizable, though somewhat antiquated. The heavy, self-conscious jocularity of Rotary and the Elks in the 1920s pretty much vanished in the next decade, along with the adolescent boosterism and the naive belief in “progress” that by 2022 had been replaced by a vague progressivism among the contemporary equivalents of Chum Frink, Howard Littlefield and Vergil Gunch. The sense of business as a romantic enterprise has disappeared too — save for the technological industry, where it has redoubled. Today, the middle classes that dominate the middle-sized Midwestern American cities are much altered from the good citizens of Zenith: better educated (or at least, more commonly endowed with college and university degrees); more widely employed in the technological and informational industries; more intellectually snobbish; and far more concerned with the sort of social status these things confer.

Money, of course, is as important as ever, but money itself is no longer enough. Babbitt and his friends have been considerably liberalized and their wives still more so, as reflected by the political polls since 2015, when Donald Trump began his rise within the Republican Party. Today, Myra Babbitt — a graduate from a community college at the very least — would certainly not approve of socialism and socialist politicians, let alone “the Squad,” but she would be horrified by Donald Trump and be socially embarrassed by a husband who stuck MAGA labels on his car and talked up Trump at dinner parties: “Oh Georgie, you sound just like the German furnace man!”

Similarly, while for the Babbitts and their friends attendance at church on Sundays is a sign of social respectability rather than of faith, their equivalents today would be slightly defensive, even apologetic, about their churchgoing habits. Conscientious adherence to an orthodox Christianity requiring a public affirmation of belief, and the determination both to form one’s opinions on the basis of it and to act upon these, would surely embarrass them. In fact, they would be more likely to seek respectability in agnosticism than in faith, or in the new pagan religion that has largely supplanted Christianity outside of the megachurch, Pentecostalist and Baptist Belts in the most benighted and unsavory parts of the country.

Conformity exerts a strain even upon born conformists like George F. Babbitt, whose midlife crisis goads him to a shallow, predictable, half-hearted and amusingly innocent rebellion against the manners, mores and ideas of early twentieth-century bourgeois American life. Prosaically enough, Lewis introduces a dull sense of a loss of sexual and romantic possibility from the second page as Babbitt, close to waking in the morning, dreams his oft-returning dream of “the fairy child… so slim, so white, so eager!” When his wife and younger daughter make a trip east in the summer to visit relatives, he engages in mild and clumsy flirtations with the wives of friends that go nowhere, though he comes close to having an affair with Tanis Judique, a widow and client of his realty firm.

Babbitt is as unimaginative and timid in rebellion as he is intellectually. He is too much a creature of his society to rebel against it. The most he can manage is mild protest, but even this is noted by friends and acquaintances. They, exquisitely sensitive to the slightest deviancy from Right Thinking, begin to suspect his reliability as a Solid Citizen and a One Hundred Percent American when, inspired by his youthful friend the socialist politician Seneca Doane, he imagines himself a blossoming liberal and defends the striking workers at the telephone office in Zenith. “They got just as much right to march as anybody else! They own the streets as much as Clarence Drum or the American Legion does!… Of course, they’re a bad element, but — Oh, rats!”

Babbitt’s rebellion is personal, not political, lacking an ideological, an existential or even an intellectual basis. Looking over his teenage daughter’s books he finds Vachel Lindsay’s poetry “quite irregular” and Mencken’s essays “highly improper, making fun of the church and all the decencies.”

Babbitt unchained — Babbitt liberated — belongs to a type of businessman that held no interest, forty years later, for Tom Wolfe or William Hamilton, the cartoonist-about-town, whose subjects were the radical chic financiers of go-go Wall Street in the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties. American civilization had not got so far as that before, not even in the Roaring Twenties.

Sinclair Lewis, like his literary mentor and supporter H.L.Mencken, was a product of the stolid American bourgeoisie; his father was a medical doctor in Sauk Centre, Minnesota. Despite Lewis’s savage depiction of his class, he never left it, though he tried to — unlike Mencken, a rebel only on the printed page, who otherwise lived a thoroughly conventional life. Lewis was frequently no better than an obnoxious drunk, assuming the role of the ignorant Midwestern hick it amused him to play in public, a parody of what he supposed sophisticated Easterners expected a small-town Minnesotan to be despite what his biographer Mark Schorer described as his life-long “notions of starched elegance.” What is notably missing from Babbitt, as from all Lewis’s novels, is a sense of mental, emotional, social and existential tension — a feeling of living at the edge of everything — that amounts to a kind of self-willed hysteria and is the dominating mood in America today. It is missing because it was absent from the 1920s, and even from the 1960s.

For a full century, George Follansbee Babbitt has been the stereotypical symbol of American provincialism, cultural ignorance and banality, anti-intellectualism and distrust of the imagination, and middle-class conformity for American intellectuals and, indeed, for sophisticates the world over. A revisionist reading of Babbitt in 2022 suggests that there are worse things in this world than social conformity, intellectual skepticism and a cynical view of intellectuals, and of bourgeois society as a whole. As the 1920s were the decade of “normalcy,” so the 2020s are becoming the decade of rapidly spreading anarchy. Between 1920 and 1929 many unpleasant and lasting institutions were introduced into American society and American life, but many of them were hardly the worst. Many worse ones — by far — have been introduced since then. Babbitt would be horrified but perhaps unsurprised.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2022 World edition.