In the summer of 1942, the Polish poet Władysław Szlengel made a detour into light verse with “The Passports:” “I would like to have a Uruguayan passport/ Oh, what a beautiful land it is/ How nice it must feel to be the subject/ Of the land called Uruguay…” Successive quatrains hymned the joys of Paraguayan, Costa Rican, Bolivian and Honduran citizenship before the final stanza declared that it was only with one of these citizenships that “one can live peacefully in Warsaw.”

The joke was serious. Szlengel was a Jewish man living in the Warsaw Ghetto; and as Roger Moorhouse’s absorbing new book, The Forgers, describes, Latin American passports were, or could be, a ticket to safety, or at least a hook on which the shreds of hope could be hung. They were forged and smuggled to Polish and Dutch Jews by a furtive and raggedy alliance of spies, diplomats and Jewish aid agencies, and what Moorhouse crisply describes as “the pious dishonesty of an honorary consul.”

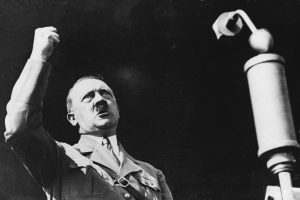

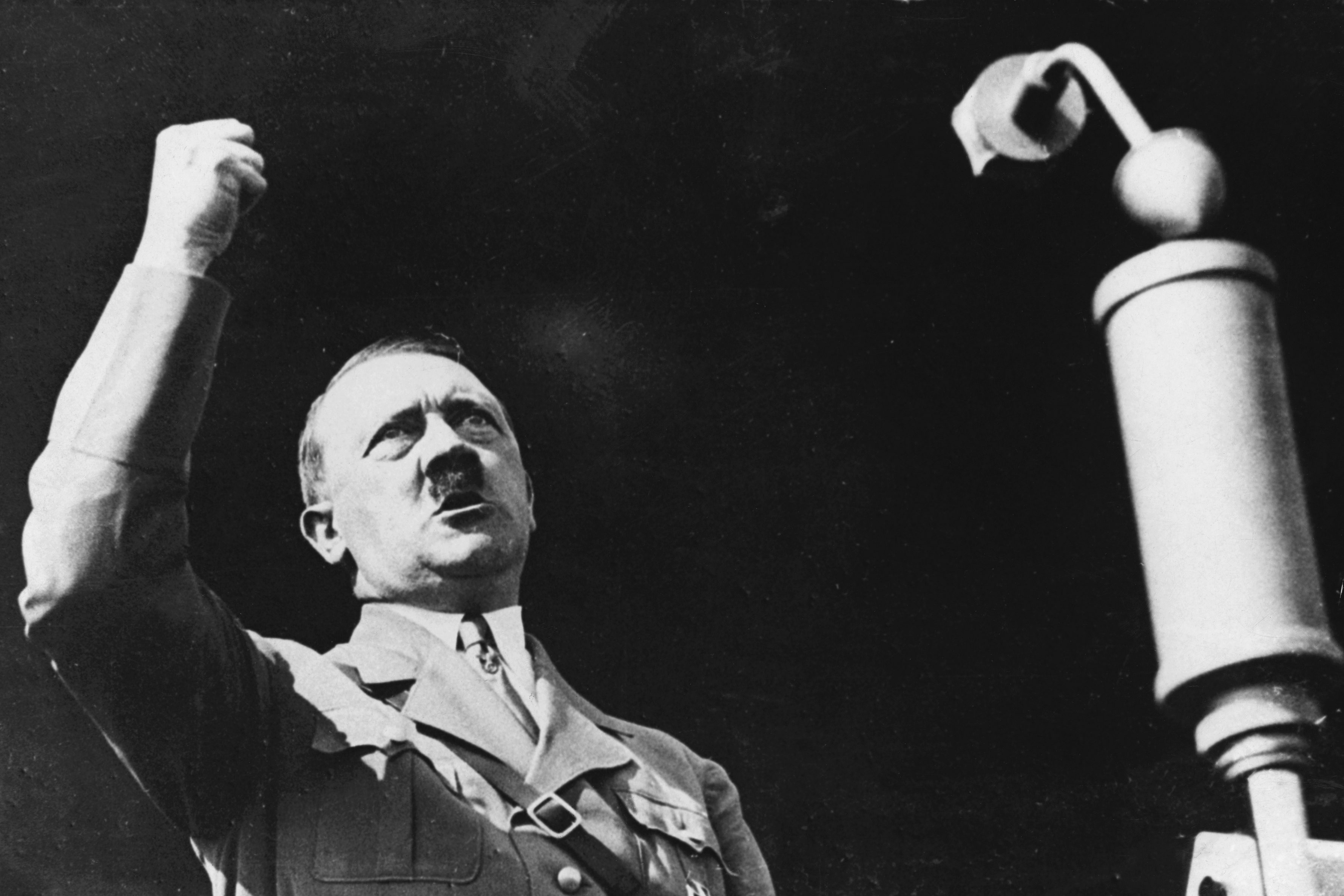

The backdrop to this is the uselessness of the so-called international community. When it became clear that Jews were being mistreated in Germany and many of them were trying to get out, representatives of thirty-two nations gathered in the summer of 1938 in the fanciest hotel in Evian to eat sole meunière and address the “migration problem.” They all regretted it most awfully: “The delegates lined up… to express their profound sympathies for the dreadful plight of the refugees and to explain why their own specific circumstances made it impossible for them to allow any increase in Jewish immigration.” In 1943, by which time the dogs in the street knew that European Jews were being exterminated, and on the same day the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto began, they repeated the exercise in sunny Bermuda, with much regret, and so on…

The people who did something about it were those who were prepared to break the rules. In Kaunas, a Russophile Japanese diplomat called Chiune Sugihara hit on the dodge (making a distinctly generous interpretation of his orders from Tokyo) of issuing more than 2,000 Japanese transit visas to help Polish Jews escape Soviet-occupied Lithuania by pretending to be en route to the Dutch colony of Curaçao. In Istanbul, a Polish consul teamed up with a Catholic priest to dole out hooky baptismal certificates to Jewish refugees so they wouldn’t count towards Turkey’s 200-Jews-a-month limit.

In Bern, Moorhouse’s hero Aleksander Ładoś, a portly fifty something veteran of Poland’s exile government who found himself chargé d’affaires ad interim (a fudge: the Swiss didn’t want to anger the Nazis by recognizing him as an ambassador), set up a network to issue aid, and then fake papers, to Jews in occupied Poland. His half-dozen or so close confederates included an honorary consul for Paraguay who supplied Paraguayan passports, and an honorary consul for Honduras who, dismissed from his post in 1941 for illegally issuing Honduran passports, pinched the consular seal and carried on knocking them out regardless.

Did it work? Oddly, it did; well sometimes — at other times didn’t. As Moorhouse acknowledges, the logic of Holocaust-era bureaucracy depended on a series of rotating funhouse mirrors. Latin American governments, on and off, didn’t mind such passports being forged, since there was no real likelihood of the bearers fetching up in Costa Rica or Paraguay; and the Nazis, at least early on, didn’t much mind conniving in the pretence that they had a whole lot of Yiddish-speaking Paraguayans on their hands, because foreign nationals — what they called “Exchange Jews” — were seen as bargaining chips to be traded in to repatriate German nationals to the Reich. If you had one of these passports, with a bit of luck you’d end up in Bergen-Belsen rather than being murdered on arrival in Auschwitz. It might give you a few more months, maybe even a year or two: another set of chances to slip through the cracks in the death machine.

As a books editor who sees dozens and dozens of supposedly “forgotten” or “untold” stories of Holocaust-era heroism pass across my desk every year, I had my doubts about this one. The subtitle is certainly an oversell. Moorhouse’s forgers were for the most part diplomats, quartered in neutral Switzerland. Their positions were precarious, and they took risks with their livelihoods, but if this really was the Holocaust’s “most audacious rescue operation,” I’m a banana. Still, it is a story that seems not to have been told much outside the academic literature, and it is deeply researched and well reported here. Inevitably, it is contextualized by an absolutely gruelling laundry list of horrors — the Warsaw Ghetto, the Łódź Ghetto, the expropriations, the exterminations, the camps, the camps, the camps…

By the end of the war the Ładoś Group had issued more than 10,000 fake documents and saved thousands of lives, though nobody knows for sure how many. Most of those who benefited had no idea where the documents came from. After the war, when Poland was thrown to the wolves at Yalta, Ładoś declined to work for Stalin’s puppet government. He raised chickens and strawberries in a farm outside Paris until the money ran out and he went home to Poland. He died in Warsaw in 1963, Righteous Among Nations, his memoirs unpublished.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.