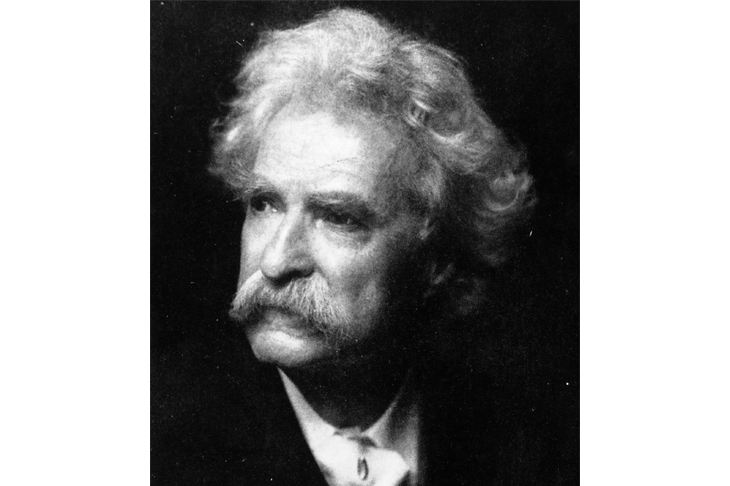

Mark Twain’s work contains in itself pretty much all of 19th-century America. This is America as she was when still, geographically and socially, more a frontier society than not; before she became heavily industrialized, urbanized and suburbanized: increasingly convergent upon the European societies from which she was descended. Twain’s America is, in short, America when she remained a unique place; even as she was evolving with lightning speed from her earlier self into something approaching her present one.

Mark Twain made an international reputation for himself with the publication in 1869 of The Innocents Abroad, a travelogue that recounts a trip of many months through Europe and the Middle East. A reader coming to the book today would doubtless be amazed to learn that it could have launched any author’s career. Not that it is without charm, humor and insight, of course. Still it is, like all of Twain’s non fiction work, long-winded, over elaborate and overstuffed according to the style of what he named ‘the Gilded Age’. There is in it too much exaggeration, overwriting, padding, discursiveness and extraneous material embedded complete and verbatim in the text — too much of everything, in fact. Yet it was also what the reading public wanted in those days, when people had the time, the attention and the sheer patience to accommodate such literary productions.

Twain’s next book, Roughing It — describing his life in the mining towns on the western frontier when he was assisting his brother, who had been appointed secretary to the governor of the Territory of Nevada, and later as a journalist in San Francisco — is similar to Innocents Abroad in form, structure and style. The same wild exaggeration, borrowed from and reflecting the tall tales generated on the frontier; the same nonstop authorial improvisations intended to display the author’s limitless imagination and his rhetorical skills (the literary equivalent of operatic coloratura); the same frequently inserted stories and other various extraneous materials; the same resulting lack of form, save for the chronological narrative. Writing of this sort, wholly out of favor with readers and critics today, was yet of a piece with the popular culture of the time, heavily influenced by the lecture platform, the Chautauqua, political rallies and camp meetings. People in those days were to a large extent self-entertainers, writing, reciting and performing their own material. Twain himself was a formidable and famous lecturer, who toward the end of his life worked himself out of debt by his appearances on the lecture circuit.

Like every great writer, Mark Twain was preoccupied with certain recurrent themes in his fiction and his nonfiction alike. Of these, the principal ones are the virtues of the Old World vs those of the New; American optimism and pragmatism vs European protocol, formality and artificiality; Catholicism vs Protestantism; middle-class niceness and conformity vs morality; hypocrisy vs authenticity and sincerity; nurture vs nature as the determinative element in human personality and character; and metaphysical skepticism and cultural relativism vs fixed truth and beliefs. Though late in life Twain cultivated a dark pessimism bordering on nihilism, in his writing he seems to have thought less in terms of good and evil than of goodness and badness, meaning naughtiness; partly, perhaps, because the protagonists of his two greatest novels are boys. Hence Tom Sawyer’s behavior, considered bad by adults, is plainly, in his creator’s view, only naughty and boyish; likewise, his stepbrother Sid’s smugness, his priggish adherence to grown-up rules and manners, are ‘good’.

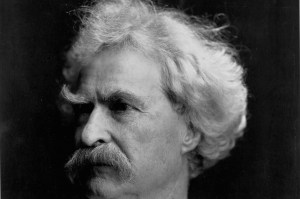

In 1906 Albert Bigelow Paine took a photographic sequence showing Twain seated in a rocking chair and smoking a cigar on the portico of a rented house in Dublin, New Hampshire, described by its subject as registering ‘with scientific precision, stage by stage, the progress of a moral purpose through the mind of the human race’s Oldest Friend’. Across the first frame Twain wrote in fountain pen: ‘SHALL I learn to be good?… I will sit here and think it over.’

On the second frame, he scrawled: ‘The redo seem to be so many diffi…’ On the third, ‘And yet if I REALLY try…’ On the fourth, ‘and just put my whole HEART into it…’ On the fifth, ‘…But then I couldn’t break the Sabb…’ and on the sixth, ‘And there’s SO many other privileges, that… perhaps…’ The final frame shows Twain staring directly at the camera as if to say, ‘Well, that’s that.’

The apparent flippancy somehow conveys something deeper even than irony, a quality that likely comes from Twain’s rejection of the popular Calvinism of the American Southwest of his boyhood that left him lacking something he was never able to find and accept in another form. Sniffing can’t and hypocrisy everywhere, Twain ‘suspicioned’ professions of goodness and religious belief. Here was an aspect of a naturally skeptical nature upon which his ironical genius as a humorist depended, and which he developed further for professional reasons. In A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Twain has Hank Morgan remark that if he had the remaking of man, he’d have no conscience because a conscience is ‘too uncomfortable’. That, of course, is Morgan speaking. Yet without doubt the most famous moment in Huckleberry Finn arrives when Huck, in mental and moral agony, tells himself, ‘All right then, I’ll go to hell’ — and tears up the note he has just written betraying Jim to his owner and the authorities up river. Twain himself once referred to ‘a book of mine’ in which ‘conscience and a sound heart’ come head-to-head, and conscience loses.

In his travel books it amused Mark Twain to pose as the clear-sighted, plainspoken, informal, pragmatic, unromantic, unsentimental and unpolished product of the American frontier, suspicious of formality and ritual though good-naturedly amused by them. Considering his jaundiced view of American Protestantism, his treatment of the Roman Catholic Church in The Innocents Abroad is surprisingly tolerant, and even in its way respectful. His description of his visit to the Duomo in Milan and the tomb of St Charles Borromeo, for instance, is signally lacking in the mildest sarcasm. His appreciation of Continental civilization — its people, its art and architecture, its slower, more relaxed and comfortable life by comparison with the hectic pace of America — seems genuine enough.

Similarly, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, a novel published 20 years later that I had erroneously remembered as a defiantly know-nothing attack by a progressive, down-to-earth 19th-century American on the backwardness and superstition of early medieval England, is in fact something wholly different. At the time, the book offended much of Twain’s American audience who read as it an unpatriotic satire on American civilization and Americans themselves: a denial of America’s self-professed superiority to Europe. Their resentment was doubtless encouraged by the rhetorical development of the novel, which begins by inviting the reader to enjoy a send-up of English medievalism and ends with a violent display of 19th-century American technique after the Yankee, having industrialized the realm, destroys a good half of it, including its nobility, during all-out civil war fought with modern weaponry of the kind Hank Morgan had manufactured at his arms plant in Hartford before he was struck on the head and bounced backward into the 6th century.

Twain’s satire, as in the scene in which Morgan, having rescued a poacher from a sentence of death for his crime, determines to send him to work in the factory he has founded, ‘where I’m going to turn groping and grubbing automata into men’, is certainly unsparing. Yet the author’s treatment of the Catholic Church is equivocal. ‘What would this country be without the Church?’ Morgan asks. And though regretting that the priests have reconciled the people to an established church, he recognizes that the majority of them are good men nevertheless.

Mark Twain’s novels — with two extravagant exceptions — are, of all his enormous literary production, the weakest and most dated of his books. The most famous of them, The Prince and the Pauper (1881), is patently a boys’ book, even if the heavily over worked theme that environment and training are everything (‘Training is all there is to a person,’ Hank Morgan remarks in Connecticut Yankee) is of no interest to the normal healthy boy. The second best-known today is Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894) — a vastly better novel, though scarcely less didactic in its dramatization of the environmental theme and the basic human equality of the black and white races.

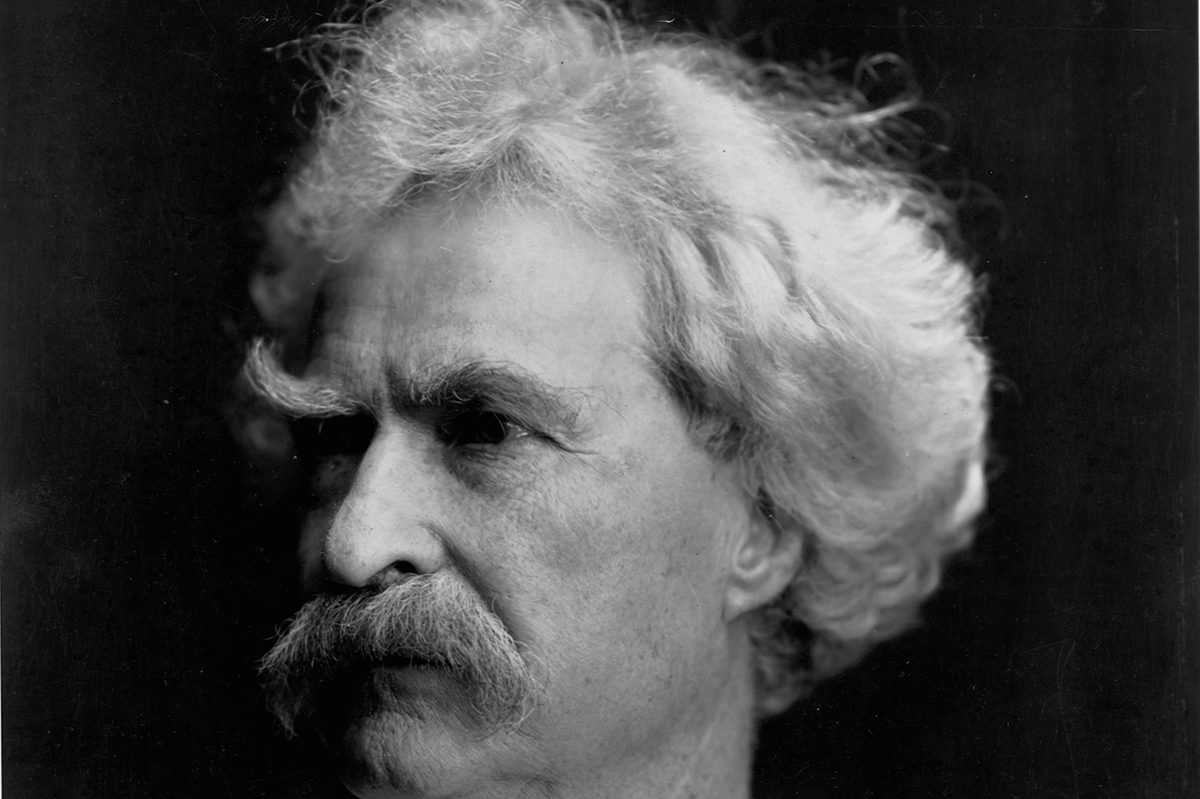

The exceptions alluded to above, of course, are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), conceived by the author as companion novels. Their chronological appearance, eight years apart, is notable for the striking, inexplicable fact that the two books are far superior to anything Mark Twain had written before or wrote subsequently.

For an artist to qualify as a genius, he only has to do it once — create a single masterpiece, that is. Mark Twain did it twice. Nothing that he had accomplished in the past, as I say, hinted at these transcendent works to come. Everyone with a knowledge of the subject is familiar with Hemingway’s judgment that all of modern American literature comes out of one book. William Faulkner said the same. Huckleberry Finn — in subject matter, treatment, language and technique — is the first modern novel written by an American. Rather, to be exact, it is the first modernist novel produced on these shores; the first in a tradition that includes Hemingway himself, Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, ends with Cormac McCarthy, and is distinguished by the poetry of form and the language of poetry.

Manifestly, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn have their faults. One of them is that in both cases Twain seems to have been uncertain as he went along about Tom’s and Huck’s ages. At times they are pre-adolescents, performing the actions of grown men; at others they are put to bed by women. And with both books, too, Twain has a problem with endings. Tom Sawyer suffers from a melodramatic and abrupt conclusion, while Huckleberry Finn ends with one of Twain’s preoccupying concerns — the romance of European culture vs the pragmatism of its American counterpart — with which the text has not been previously concerned, and from which Twain creates an elaborate farce unworthy of the novel’s major theme, as mighty as the Mississippi River itself. No matter. Huckleberry Finn is as beyond spoiling as it is beyond the reach of rust and the moth. It is a book that will live on in Heaven, having perhaps earned its unbelieving creator a place there.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.