This collection of stories is so assured, and delivered with such aplomb, that it’s hard to believe it’s a debut — and, as it turns out, that’s because it isn’t. Although Elsewhere is Yan Ge’s first book written in English, she is a seasoned novelist in China, where she has been publishing fiction for more than twenty years.

For the past decade, Ge has lived in Britain and Ireland, and the collection captures the spirit of both her birthplace and her adopted homes in a variety of registers. The stories set here have a whiff of autofiction to them, but transcend their origins with style and wit. In “Shooting an Elephant,” Shanshan, a Chinese woman living in Dublin with her reporter boyfriend Declan, can’t understand how the IRA kingpin Thomas “Slab” Murphy got his nickname. “Perhaps he has a flat forehead?” But saying things in this sparky fashion is a way of not saying other things. Shanshan, Declan says, “should focus on getting better” (from what?), and there is an austere perfection in the evasive reference to her mother’s death, a single line: “A policewoman had asked her ‘Can you confirm the victim’s identification?’”

Similarly, the story “Stockholm” describes with antic energy a writer’s difficulty in presenting a professional face at a literary festival while she dashes to the toilet to express breast milk and frets that her head is so filled with “nappies, pee, poop” that she has lost “the ability to write or even perform like a writer” — all the while surrounded by increasingly terrible literary people who are no doubt entirely invented.

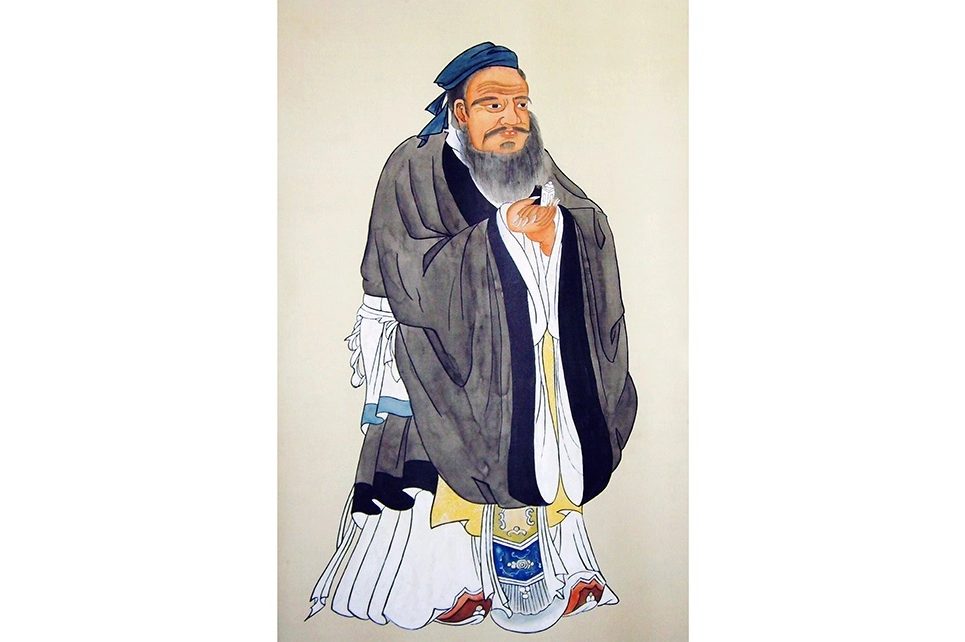

But it’s Ge’s stories set in China that are the most formally adventurous. They range from a tale of arguments and sex in the aftermath of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake to a gripping account of the (real) death sentence imposed on the eleventh century polymath Shen Kuo. Most impressive of all might be the closing novella “Hai,” which unearths the politics around the succession to Confucius in the fifth century BC.

Here, struck by the quality of writing irrespective of its setting, we wonder what we have been missing in Ge’s earlier, untranslated fiction. In the story “No Time To Write,” the narrator says that to write is “to go down into my memories like a miner, get my hands dirty and dig out the nasties.” Another character demurs: the past is “just in your head. And it’s in everybody’s best interest if you just keep it in your head.” I tend to agree — but we will allow for exceptions.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.