Welcome to Mingheria, “pearl of the Levant.” On a spring day, as the twentieth century dawns, you disembark at this “calm and charming island” south of Rhodes from a comfortable steamer after sailing from Smyrna, Piraeus or Alexandria. A crew of Greek or Muslim boatmen will row you to the picturesque harbor of Arkaz, flanked by the radiant White Mountain and the gloomy turrets of the medieval castle.

The fragrances of honeysuckle, linden trees and the famous Mingherian roses waft over azure seas. Admire the ancient churches and newer mosques, the neo-classical State Hall, the grand buildings funded by the sultan’s government in faraway Istanbul. Savor figs, oil, nuts and cheeses in the bustling markets. As for those rumors of banditry by Orthodox or Islamist renegades in the bare hills: mischievous tittle-tattle. Infection? You’ll find no disease here…

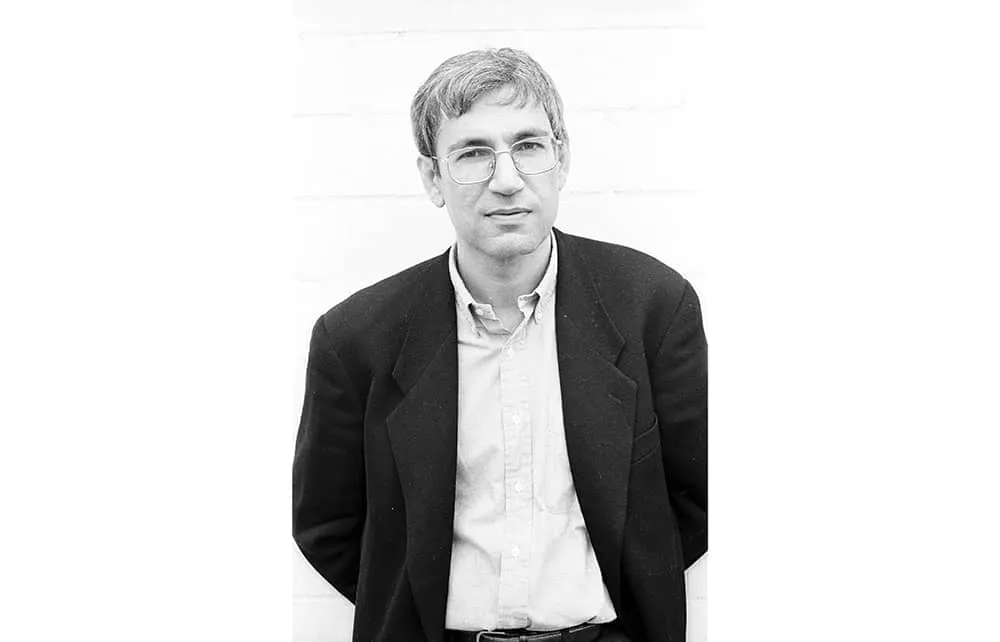

Orhan Pamuk began writing his tenth novel in 2016. In 2020, reality caught up with Turkey’s Nobel laureate. Nights of Plague chronicles eight months of pestilence, lockdown and dread on a fictitious Aegean island. In 1901, an outbreak of plague scourges its people — equal numbers of Christians and Muslims — while the tottering, panicky Ottoman state loses its grip.

In his novels of Istanbul past and present, Pamuk relishes meticulous, immersive world-building. He remakes the city street by street, smell by smell, brick by brick. Over 700 pages, he does the same for imaginary Mingheria. His dream island hosts a “three-dimensional fairy tale” — the backdrop for a densely crosshatched parable not just of an epidemic and its outcomes but nationalism, modernity and group identity. Along the way, he uncovers “mysterious links… between history and objects, and nations and writing.”

Pamuk frames his journal of a plague year as a narrative compiled by a modern historian from letters written by Princess Pakize. She is the invented daughter of the actual Ottoman Sultan Murad V, who in 1876 was deposed and confined to palace arrest by his reformist but authoritarian brother Abdul Hamid II. Raised in a gilded cage, Pakize finds liberation of a sort in marriage to the progressive “doctor and prince consort” Nuri. After the murder on Mingheria of the Ottoman public health chief, Bonkowski Pasha, Nuri and Pakize are despatched there. They must hunt down the culprits and battle a galloping epidemic that the enfeebled empire wants to deny.

Back in Istanbul, Abdul Hamid devours detective stories (as he really did). Rebel provinces break away; the imperial map “continues to shrink.” On Mingheria, meanwhile, “Sherlock Holmes methods” and scientific epidemiology vie with cruder investigative measures (arbitrary detention, mass isolation, foot-flogging and incineration). New brain and old brawn compete in the search both for Bonkowski’s shadowy killers and the sources of the plague.

Stricken Mingheria becomes a microcosm of the Ottoman twilight. As the death toll mounts, the island’s amiable, conciliatory governor Sami Pasha — with his twin-dialed pocket watch that tells the time in both western and Ottoman fashions — sees authority slip away. Well-off Greeks flee. Wary Muslims, inflamed by sectarians, revolt against lockdown: “Nobody ever wants a quarantine.” From the lodges of “charlatan sheikhs” to dank cells where victims of “chief scrutineer” Mazhar Effendi shiver, Pamuk crams his Mingherian map with precise, almost obsessive detail. It thickens the texture but slows the pace. Ekin Oklap’s cleverly voiced translation captures our historian’s fussily pedantic, sometimes tortoise-footed, story-telling. Go with its leisurely flow, however, and the island saga can exert the hypnotic pull of those historical soaps Turkish TV does so well.

In this “time of anarchy,” unrest boils over into insurrection, both religious and secular. The rise of Mingherian “romantic nationalism,” fronted by the dashing Major Kâmil, lets Pamuk fire off sly barbed darts at the official Turkish cult of Atatürk. On the reborn isle, the mystique of a holy nation and its unique language makes the affirmation of Mingherian identity “as sacred as an act of prayer.”

Soon “nationalist fervor blurs the lines between… myth and reality.” Mingheria becomes an island of ideas, twinned with Atlantis or Utopia. Yet the novel also traces the grotesque progress of the pestilence as faith and science tussle: the sheikhs’ “esoteric knowledge” on one hand, “microbes and Lysol” on the other. Palace coups and popular uprisings multiply as the plague summer repeats, at speed and in miniature, the history of revolutionary epochs. A late twist thrusts the princess and her doctor husband into the spotlight. On this “stage of world history,” Pakize will not waste her privileged life “standing in a corner like a faded rose.”

As it pivots between saga and satire, mystery and pseudo-history, Nights of Plague can feel as overloaded as an Arkaz boatman’s caïque. Pamuk, though, shows nous, charm and cunning as he keeps his bulky cargo afloat and on the move. If this generous hybrid of epidemic soap opera and novel of ideas has becalmed patches, it stirs the senses and flexes the mind. You will be sad to leave lavishly imagined Mingheria, where “a view of the sea and a trace of its scent” can always “make life seem worth living again.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.