With a new show at the Whitney, Edward Hopper’s New York; a new documentary film from director Phil Grabsky, Hopper: An American Love Story; and a recent exhibition organized by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the work of one of the most popular yet seemingly inscrutable American artists of the twentieth century is receiving a great deal of renewed attention.

In his paintings, Hopper’s hard-edged realism, impressionistic plays of light and passages of intensely saturated color compete for attention. What has always captured the public imagination is the relative isolation of the figures that appear in his work. Search for articles about Edward Hopper online, and many will describe his art as an exploration of loneliness. It turns out that this line of thinking is utterly wrong.

From a biographical perspective, the conventional wisdom makes sense. Hopper was somewhat taciturn, and aggressively disinterested in achieving fame or fortune. He had no interest in being the flavor of the month, or in hobnobbing with the beau monde; he did not leave a school of artistic followers. No doubt he would have loathed social media, given that he rarely socialized at all.

Like many great artists, Hopper had a talent for perceiving the world around him that was honed over decades of active seeing. He managed to create images that invite us to stop, look and not take the easy way out by accepting what is only on the surface.

“I think that Hopper must have always believed in his ability to see the world and create something important on canvas,” notes Kim Conaty, curator of the Whitney’s new exhibition and author of the accompanying catalog. “For an artist, you need to believe that you are bringing something to the world. And at the same time, he did, really, through the end of his days, live a rather ordinary existence.”

Filmmaker Phil Grabsky, director of the new Hopper documentary, thinks that Hopper’s intense sense of focus is key to understanding both the man and his work: “He’s clearly highly intelligent, and I think he knew he was a top painter. Hopper wasn’t really interested in being famous, but what he did want was to be respected. ‘Those people that wrote me off, I showed ‘em.’ There’s something intriguing about the psychology of that.”

Unlike many modern and contemporary artists, Hopper only painted two or three pictures a year, each being thought out entirely in his head for weeks or months before he set to work on canvas. While his peers often had stacks of canvases piled up in the studio awaiting buyers, Hopper would complete a single painting. He’d then turn it over to a gallery to sell it. Hopper also never really changed his style of painting to suit the opinions of others or to reflect on the changing times.

To look deeply at Hopper’s art requires the understanding that it is not seeking to depict highfalutin concepts but rather to show what it is like to be inside Hopper’s mind: what he sees, experiences, thinks about, and then expresses with his brush.

“The whole answer is there, in the canvas,” he once remarked. “If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.” Even the titles of his pictures tell us virtually nothing about what he chooses to show us, let alone why.

Hopper was always actively exploring his surroundings, whether striding down a city street or scouting coastal bluffs like a film director seeking that perfect shot. Indeed, he spent weeks at a time going to the movies, soaking up what he saw on the screen, with the intense light and shadows of film noir (not surprisingly) being his favorite genre. What might be perceived as something like ennui in Hopper’s work is utterly belied by the methodology with which that work was created.

As much as Hopper is an artist with an intense intellectual aspect to his creative process, he never forgets that someone else will be looking at what he paints. Grabsky notes that “there are absolutely three people in their relationships: there’s the canvas, the artist and the viewer. I think Hopper thinks very hard about the person who is going to be looking at the painting.”

At the same time, Hopper’s work ought not to be read as an allegorical representation of the human condition because he did not intend it to be. In an interview conducted during his later years, Hopper rejected the commonly held view that his paintings were depictions of the idea of loneliness. “Those are the words of critics,” he scoffed, “and I can’t always agree with what the critics say.”

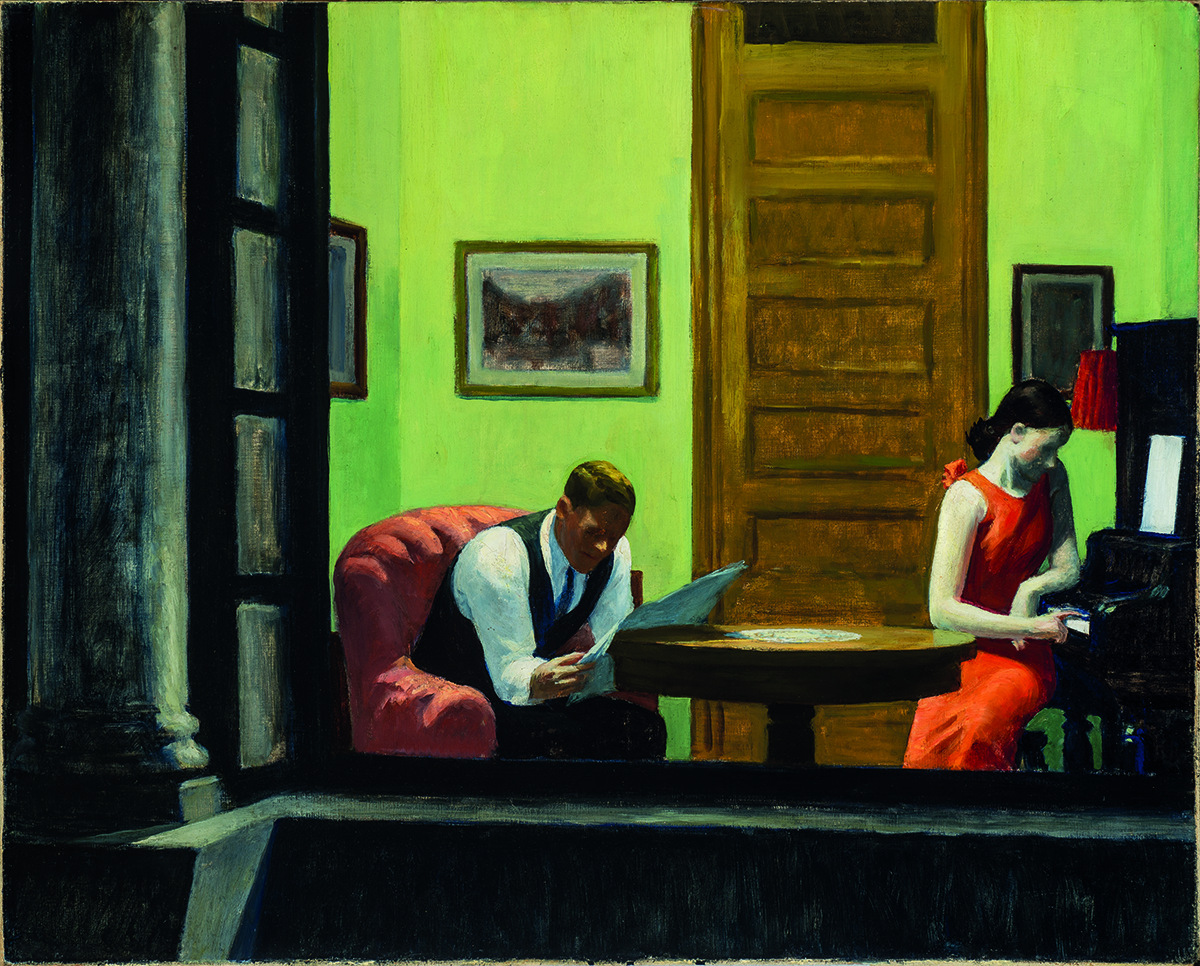

In his paintings Hopper typically depicts locations with one or perhaps a few figures, although often not including any figures whatsoever, and then lets the viewer decide what, if anything, is going on. Something may just have happened, or something may be about to happen, or nothing may be happening at all. There is no specific narrative purpose behind what the viewer sees. Seasons of the year may be suggested, or the style of dress worn by the figures may change, but for the most part a Hopper picture displays a time and place that cannot be easily identified.

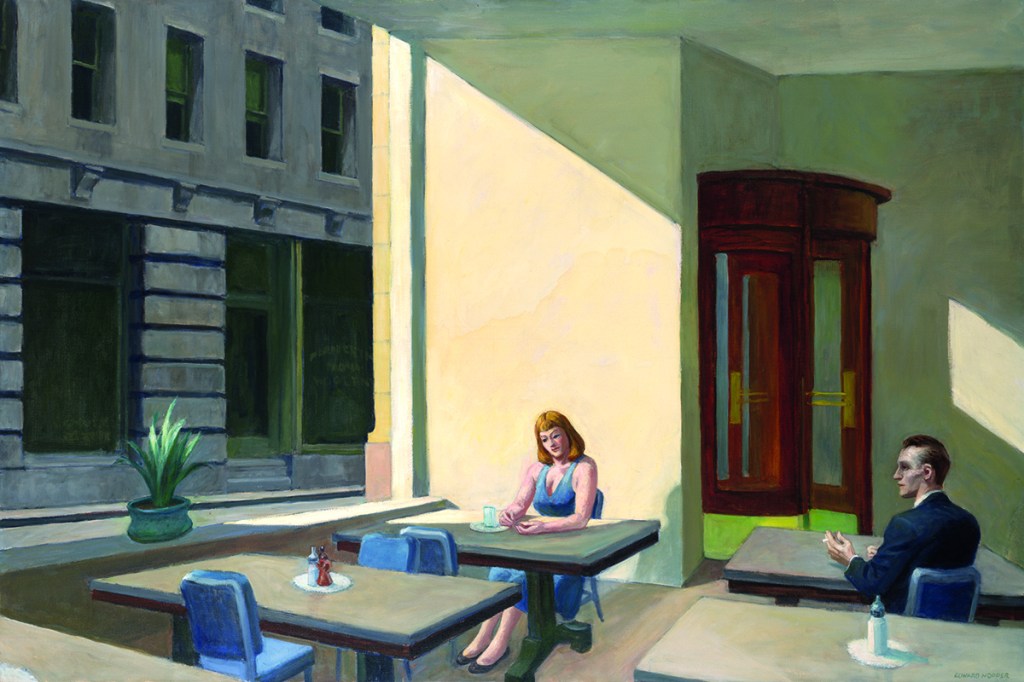

In putting together the exhibition for the Whitney, Conaty gained a greater appreciation for Hopper’s evocation of a timeless sense of place in his work. “With an artist as iconic as Hopper,” she notes, “it’s hard sometimes to remember that he was a human being who worked in a specific time and place. And given the fact that he lived and worked in New York for over six decades, he saw the changes that were going on around him, and he thought about those aspects of the city that were perhaps changeless. In his work there’s often this fascinating negotiation between reality and fantasy, and between change and changelessness. And in that sense, you get these compositions that feel really enduring, even today, in a work such as ‘Automat,’ there’s something that feels like a real space.”

The figure sitting alone in “Automat,” one of Hopper’s most iconic paintings, has often been interpreted as being lonely or bored. Conaty isn’t buying it. “Hopper came out quite strongly in his lifetime saying that his work was not about loneliness, and that word in particular was a word that he did not agree with. So, if we’re looking at this lone figure in an automat, we could just be looking at someone finding that moment of solitude or stillness in the midst of a big, bustling, ever-changing world, and that is something quite beautiful and enduring.”

For Grabsky, the conventional wisdom that Hopper portrays people who are feeling alone and trapped, such as the figures in “Nighthawks,” who don’t seem to have a way out of the diner where they are gathered, is missing the point. “You could certainly do an alternative take on Hopper that feels more claustrophobic,” he remarks, “but that would be better suited to a stage play. People really misread him as being claustrophobic. We know we are fighting a tide of superficiality today, and what Hopper was trying to do even back in his own day, was to encourage people to look at things more deeply, not just at what they appear to be on the surface.”

A critically important fact to keep in mind when looking at Hopper’s work is the fact that he began his professional life as an illustrator, and it took some time for him to turn into a professional painter. Although the young man from Nyack, New York, had studied under the great Robert Henri in Manhattan and then in Paris on several occasions between 1906 and 1910, his stardom was a slow burn. This may have partly been because it was the era of those who took the established truths of Western art and smashed them to pieces to fashion them into something new, whereas from the beginning of his artistic education, Hopper deliberately continued in the vein of realism that stretched back to the Old Masters (even as he absorbed influences from more recent movements, e.g., Impressionism).

What is particularly curious about Hopper, however, is that he did so largely in isolation from his peers. Like many American artists arriving in the City of Lights for the first time, Hopper marveled at the grace and beauty of the city, its diffuse light and glowing shadows, and its handsome buildings. He noted that from his boarding house in Montparnasse, he could see the great basilica of Sacre-Coeur rising atop Montmartre, where avant-garde painters, sculptors and characters of all sorts famously met and mingled – but he himself never went there.

“Whom did I meet?” he remarked, when asked about his time in Paris. “Nobody.”

When he finally returned to America and settled in New York, the work Hopper took on as an illustrator boiled down to paying the bills. “I was always interested in architecture,” Hopper observed, “but the editors wanted people waving with their arms.” He did what he had to do, arm-waving and all, and in the meantime (between 1913-23), he did not sell a single painting.

Once he finally began to receive recognition, in no small part due to the efforts of his wife and fellow artist Josephine Nivison to get his paintings shown, Hopper was able to put aside his day job in order to pursue his true passion for painting. Nevertheless, as shown in the Whitney exhibition, many of these illustrations, as well as the etchings Hopper produced during this period of germination, would go on to provide the framework for his later compositions.

In his earlier works, on paper, an illustration that was meant to sell men’s suits may later transform into a setting or an individual figure in one of Hopper’s canvases. What vanishes are the accompanying explanations. This is a decidedly intentional act on the part of the artist, who has no intention of telling us what we are to think about when examining his work. What emerged, beginning in the 1920s and continuing for the rest of his career, was the work of an ex-illustrator, who was no longer interested in illustration, per se.

“I have a suspicion,” notes Grabsky, “that Hopper knew that he was offering up multiple interpretations. He was a very wily painter. There’s no question in my mind that Hopper is playing an intellectual game with his audience: you need to work out what’s happening in the frame. Hopper knew exactly what he was doing, it’s just something that’s slightly unnerving. Like a great filmmaker, it’s as much about what you leave out as you put in.”

Conaty agrees. “There’s something startling about the way that he depicts figures, for example. You’ll note that these figures feel like types: there’s no sparkle in their eyes, there’s a lack of expression, and we know from his training that this was not from a lack of ability. Hopper could render a figure brilliantly, but he’s not trying to render a specific person with a specific feeling.”

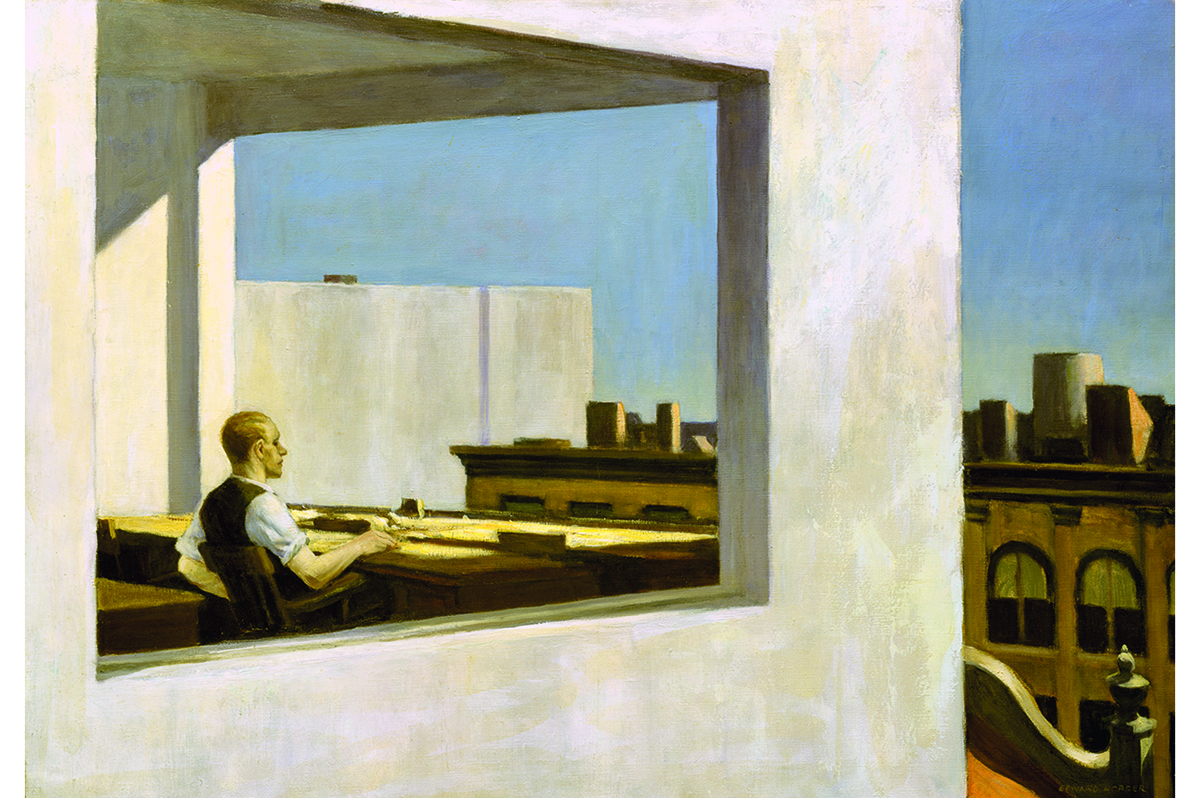

Throughout his long working career, whether in New York, in coastal New England, or on long car trips across the country with his wife, Hopper returned to the idea of place, where layers of possibility bring about uncertainty for those who happen to find themselves there. In New York, for example, Hopper never painted skyscrapers, even though they were going up around him all the time. His images of New York are timeless, easily mistaken for depicting locations in other cities, which is part of his intentional, nonspecific presentation of the elements of place. It’s why buildings of all sorts are often far more interesting to Hopper than the people who are within or without them. “Well, I like buildings,” he once commented in an interview. “And I like people…somewhat.”

“Cities are a kind of palimpsest,” notes Conaty. “And there’s a particular human response that people have to the sort of persistent change going on in them. It’s both a new-found love for what was there, and an anxiety around what is to come. You feel that in the tension of the paintings between what was, and what could be.”

For Grabsky, this is part of what makes Hopper a quintessentially American artist, and the title of his film hints at that. “Hopper can look straight through crowds and ignore them, and see the structures behind them, but he can also see what about them makes them American,” he observes. “Artists like Hopper are content just to look at local, American subjects; they don’t need to go to Europe anymore. They want to look around them and ask, ‘What is America?’ I think Hopper is very tuned in to that.”

As described in the documentary film, not long ago a cache of letters between Edward Hopper the art student and someone whom he had a crush on in Paris came to light. In these letters, Hopper’s unrequited regard for the object of his affections somehow survived for an extended period of time, despite her repeated attempts to give him the brushoff. “I do wish you wouldn’t take everything so alarmingly seriously,” the young lady wrote to him on one occasion. “I don’t think you at all reasonable.” The young Hopper couldn’t quite resist the urge to overthink.

By the time he became one of America’s most famous artists, Hopper finally got the message. “So much of every art is an expression of the subconscious mind,” Hopper observed in an interview, “that it seems to me most of all the important qualities are put there unconsciously, and little of importance by the conscious intellect. But these are things for the psychologists to untangle.”

In the case of Hopper’s work, it is time for a similar reassessment, in which his work no longer acts as a mirror for the perpetually self-absorbed. Here was a painter with no interest in portraying feelings of loneliness or isolation or in taking everything about himself with deadly seriousness. Instead, his expansive, layered work, built up over a lifetime of careful observation, allows a wealth of possible interpretations, which is far more interesting and indeed challenging when considering his output.

Edward Hopper’s New York is at the Whitney Museum of American Art through March 5. Hopper: An American Love Story is currently screening in select areas. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.