At a moment when words like “jihad” and “genocide” fall perpetually from the lips of pundits, professional activists, and policy makers, Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two seems a rather subversive spice to sprinkle into our combustible culture. While both parts of Dune comprise a complex film that defies simplistic one-to-one allegory, at times Villeneuve’s richly imagined epic places a finger on the familiar, the historical, just as it points its others toward a fiction set amongst the stars.

In the second half of this adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel, Paul and his mother, Jessica, have escaped the initial assault on House Atreides to shelter with Fremen insurgents, but Harkonnen death squads pursue them. The film’s thrilling first act sees Paul prove his usefulness as he fights alongside his Fedaykin (a reworking of the Arabic Fedayeen: “those who sacrifice themselves”) love interest, Chani. She’s the human heart of the film — played with warmth and wrath by the preternaturally-gifted Zendaya — and perhaps, its heroine.

We pick up where Part One left off: the Atreides have been betrayed by the aging Emperor (Christopher Walken, even more deadpan than usual) in order to keep the spice flowing, the all-important drug, melange, that allows humans to engage in space travel (“Power over spice is power over all,” an epigraph informs us). And standing in the wings of this space opera, operating the true levers of power, a Witch Matriarchy called the Bene Gesserit who manipulate the Universe through propaganda, parlor tricks and eugenics.

When the Emperor’s daughter, the Bene Gesserit-trained Princess Irulan, asks the Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam (an always-excellent Charlotte Rampling) about hope, the head witch informs her that the Bene Gesserit “don’t hope; we plan.”

Princess Irulan seems to be the key that will unlock the door of our anti-hero’s journey; Paul’s pathway will lead through her. Played by Florence Pugh, the princess is truly her father’s daughter — her one expression is a kind of disinterested vigilance and her other expression does not exist. This works well as Irulan is the dispassionate narrator of the tale; the film we’re watching is her diary come to cinematic life.

Since landing on Dune in Part One, the indigenous people of the planet have looked to Paul as a messianic figure who will Make Arrakis Great Again, but Paul continues to insist he’s not a messiah — just a humble freedom fighter like Chani, seeking revenge for what was done to his family.

Of course, Paul doesn’t suffer from a one literjon of humility. He’s horrified by what becoming the Fremen messiah will mean. In the first film, after the Harkonnen ambush, Paul has a vision of himself as this messianic figure, the Lisan al Gaib.

“That’s the future,” he tells his mother, narrating his revelation. “It’s coming. Holy war spreading across the universe like unquenchable fire. A warrior religion that waves the Atreides banner in my father’s name. Fanatical legions worshipping at the shrine of my father’s skull. A war in my name! Everyone’s shouting my name!”

The films use the terms “holy war” and “crusade,” while the novel (mostly) uses “jihad.” Herbert relied heavily on Muslim culture and theology when writing his masterpiece and since the release of Part One in the fall of 2021, Twitter-lectuals have lectured each other about Villeneuve’s depiction of the Fremen, accusing the director of cultural appropriation, Orientalism, Exoticism, etc. Part Two will only inflame them further, and, if they’re paying close attention, cause them to combust.

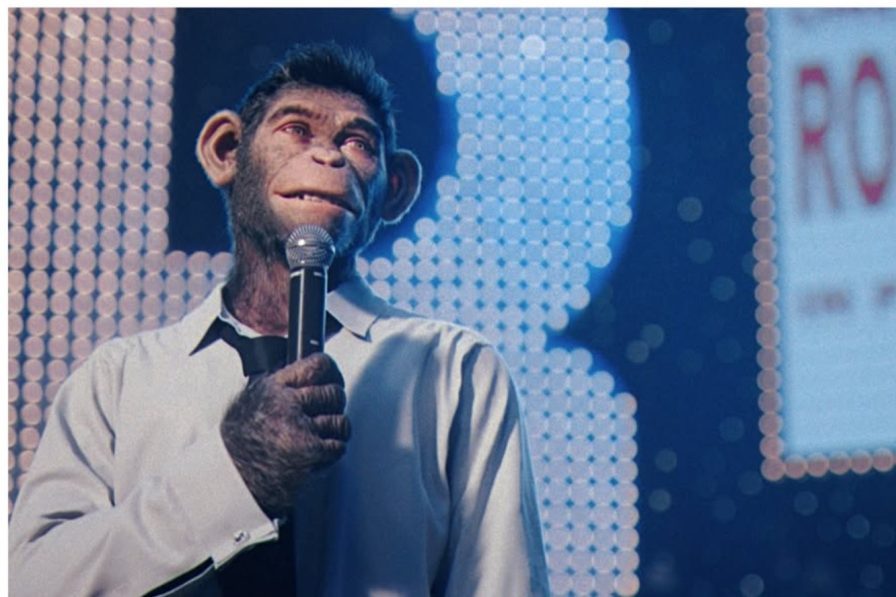

Standing in stark contrast to the Muslim-coded Fremen are the flagrantly fascist Harkonnen. We didn’t see much of their home world in the first part of Dune; Villeneuve more than makes up for that in second, staging a Nuremberg-style rally in Riefenstahl black and white, the Harkonnens chanting, saluting — all but goosestepping — as they watch a gladiatorial match between the surviving members of House Atreides and the psychopathic Feyd-Rautha, nephew of Baron Harkonnen, played to terrifying perfection by Austin Butler who we last saw as a pompadoured Elvis.

Villeneuve might have introduced this Harkonnen villain in a way that called any culture to mind — Herbert himself chose the name because he thought it “sounded Soviet.” In David Lynch’s adaptation of Dune, the decadent, rust-streaked Rome of a steampunk Caligula comes to mind. Villeneuve chooses to dress the skinhead Harkonnens in Hugo Boss-black, further conjuring comparisons with the Third Reich. I realized then that the director might be up to something a good deal more impish than Part One had led me to believe.

Speaking to IndieWire about this scene, Villeneuve said, “The idea that the sunlight, instead of revealing color, will kill color [and] will bring some feeling of a binary world where things are black or white, and this fascist and totalitarian environment will give me the opportunity to create images that will resonate and feel like an old, World War Two fascist movie.”

When Paul drinks an elixir that comes from a drowned sand worm, he experiences a vision that destroys any hopes he had for heroism. Saying more would spoil the film’s major reveal, but leaving the theater, I recalled that, in Dune Messiah, Herbert’s sequel to Dune, Paul casually references Hitler: “He killed more than 6 million. Pretty good for those days.”

The final act of Dune: Part Two marries the Atreides, Harkonnen and Fremen in an unsettling way. The Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother tells Paul’s mother, “You of all people should know. There are no sides.”

No sides?

Apparently, there aren’t and since viewing the film, I can’t stop thinking about its vision of oppression — particularly the press inside that oft-used term. Dune gives you the sense that, by holding something or someone down, you’re spring-loading it, charging it with energy. The Fremen have been hunted like vermin by the Harkonnen who constantly refer to them as “rats” — a slur that proves prophetic when Muad’Dib, the Desert Mouse, unleashes his vengeance. As Princess Irulan said of the Fremen earlier in the film, “Repression only makes their religion true.”

Will Paul accept his destiny as genocidal messiah? This occupation wasn’t his first choice.

Of course, it wasn’t Hitler’s, either.

Leave a Reply