In February 1900, a critically acclaimed art exhibition went up at a Barcelona café called Els Quatre Gats. It was neither the first nor the last show mounted at the establishment, a popular drinking spot for avant-garde artists, writers and others. It was, however, the very first solo outing for one of the café’s regular patrons: a brash nineteen-year-old local art student named Pablo Ruiz Picasso.

It has now been fifty years since Picasso died, on April 8, 1973, and even as that anniversary is being commemorated worldwide with new exhibitions and publications, he has never really faded from public consciousness. His art and even personal objects associated with him are avidly collected, and he continues to inspire filmmakers, musicians and other artists.

To mark the half-century, I recently invited two art experts to lunch at Els Quatre Gats, both to discuss the café’s importance in launching Picasso’s career, and to consider the question of whether Picasso merits “cancellation” in what passes for culture today.

Els Quatre Gats opened in 1897 as a kind of hommage to Le Chat Noir, the famous Parisian café which had closed the same year. Artist and impresario Pere Romeu, who had worked as an entertainer at the Montmartre watering hole, wanted to replicate its atmosphere and influence in Barcelona, a city that was rapidly growing and embracing new ideas in a host of creative, intellectual and technological fields. Romeu gained the backing of three friends who, like him, had spent a great deal of time in Paris — artists Ramon Casas and Santiago Rusiñol, as well as critic and sometime painter Miquel Utrillo. The name of the new establishment was simultaneously an homage to its inspiration, a nod to the four “cats” who were its founders, and a reference to a Catalan slang expression for a group of weirdos.

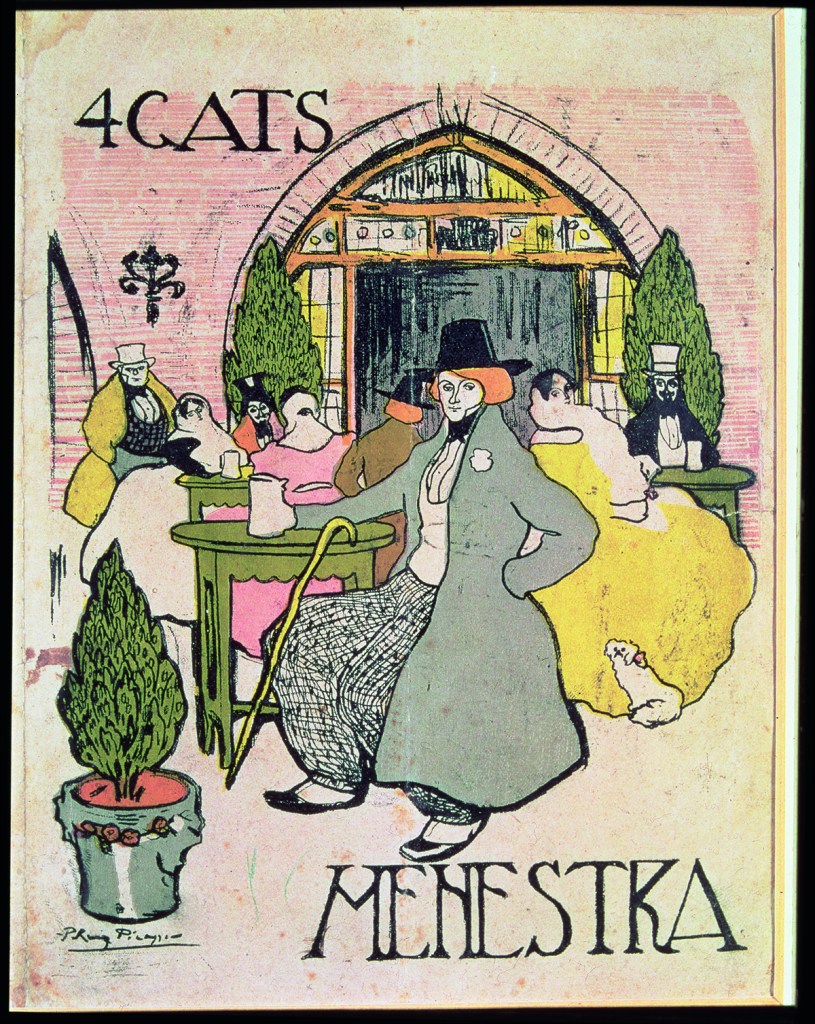

Housed in an exuberantly decorated building by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, a major proponent of Modernisme, the long-lived Catalan incarnation of what we commonly refer to as Art Nouveau, the café was filled with extraordinary works of art created by many of its regulars. Indeed, its menu cover was designed by Picasso himself. Although the original incarnation of Els Quatre Gats closed in 1903, thanks in part to Romeu’s being unable to run it profitably, some decades later it was reopened and beautifully restored.

Today’s Els Quatre Gats still features many traditional Catalan specialties, although given Barcelona’s well-earned status as a world food capital, things are perhaps a bit more elaborate than Romeu would have been able to turn out of his kitchen. For our Picasso luncheon we enjoyed dishes such as eggplant roasted in oak charcoal and topped with sweet onion, hazelnuts, herbs and goat cheese; veal cannelloni baked in a truffle béchamel sauce; black-leg organic chicken from Catalan wine country, stewed with plums, raisins, pine nuts and shavings of foie gras. And after some debate, which is only to be expected in an area as well-known for its wines as for its food, we settled on a fruity, blended white from a newer winery in the Empordà region of Catalonia called “La Vinyeta,” given the first name of one of my guests.

Vinyet Panyella is a writer, poet and cultural researcher specializing in modernism and its successors, and has published studies on Ramon Casas, Santiago Rusiñol, Miquel Utrillo and others. She served as director of the Sitges Museums from 2011-19 — the group includes Cau Ferrat, Santiago Rusiñol’s beautiful seafront home and studio. Since 2019, she has chaired Catalonia’s National Council for Culture and the Arts (CoNCA). My second guest, Gabriel Pinós, is director of the Gothsland Gallery and co-founder of the Museu del Modernisme, and serves as president of the Ramon Casas Association.

In order to further understand the attraction of Els Quatre Gats for the young Picasso, and its significance in his development as an artist, we discuss the unique atmosphere of what was something more than just a place to get plastered on the cheap.

“The atmosphere was what gave this place character,” notes Panyella. “This was a kind of anti-art gallery, or anti-salon space. If we were to try to find some contemporary vocabulary so that people today can understand what this place was, we could call it a creative laboratory. All kinds of people came here.”

Pinós adds, “The founders of Els Quatre Gats were active in the modern art movements of their time, especially in Paris, and they were bringing back what they had seen to Barcelona, acting as art-world revolutionaries here. So all of the innovative things that are going on in the art world outside are also going on here, in this place. It’s why one commentator said, if you’re feeling restless or want to learn something new, you need to go to Els Quatre Gats.”

“They were selling things that were shown here, too,” Panyella adds. “At Cau Ferrat for example, the early works by Picasso and [Isidre] Nonell and others that Rusiñol had in his collection, he originally bought here, at Els Quatre Gats. And in addition to having exhibitions and performances, people who were culturally important at the time came here, as they were visiting or passing through Barcelona.”

“This was really the place for artists, intellectuals, people from all over to get together and have a good time,” notes Pinós. “And the people who were building and modernizing the city of Barcelona at the time came here as well. Picasso and the other young artists who came here wanted to know what was going on, and what their elders were doing — their successes in Paris, their new ideas. So here was a place that modern-minded people could come and spend time together, and Picasso wanted to be around them.”

The perspicacity of the young Picasso, learning by associating and drinking with artists a generation older than himself, proved more important to his development than what he was being taught in art school. This was why Picasso came to Els Quatre Gats almost every day, and often skipped class in order to do so.

“He wanted to see what other artists were doing, like those who were painting the seaside, or gypsies or poor people,” Panyella explains. “Picasso was like a sponge with all the art he looked at, but during this period he’s really interested in seeing what Ramon Casas is up to.”

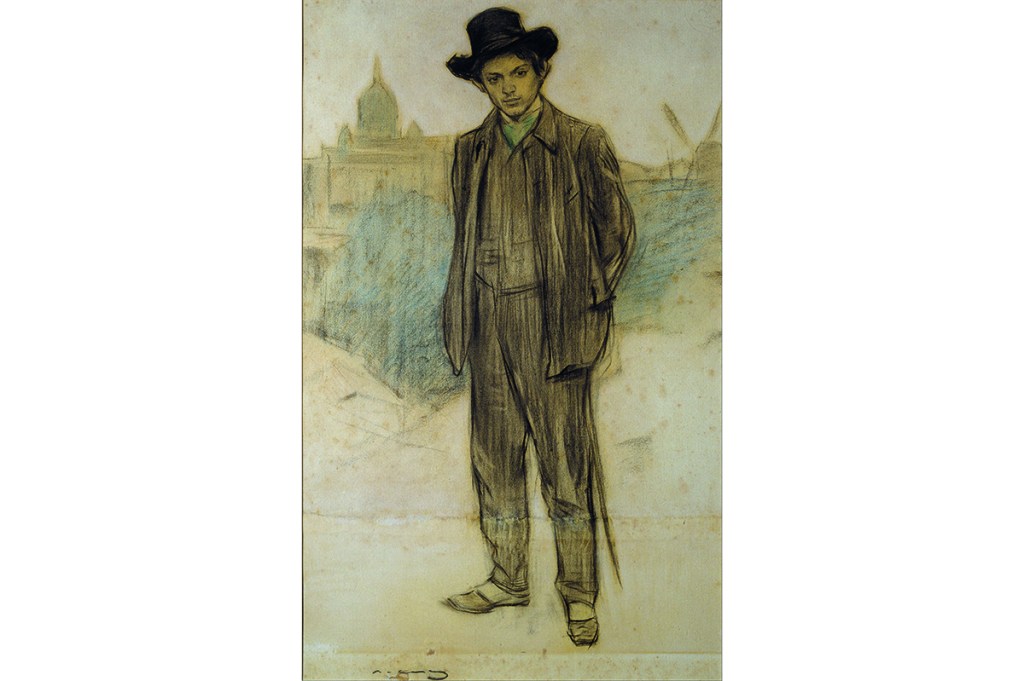

In fact, that very first Picasso solo exhibition was a kind of “in-your-face” move, with respect to Casas and the older generation. Casas had previously exhibited portraits of those who frequented Els Quatre Gats; now Picasso decided to do the same thing for his first show, but in his own style, creating even more modern-looking watercolor and charcoal renderings of some of his fellow “cats.” It’s an example of the kind of audacity and self-confidence that Picasso demonstrated throughout his career. “He was a young fellow,” notes Panyella, “who was saying to people like Casas and the others, ‘Oh, you’re the establishment now? Well look at what I can do.’”

“After seeing Picasso’s show here,” Pinós observes, “Casas went on to do a full-length portrait of the young Picasso. That means that, as far as Casas was concerned, Picasso was no longer a nobody. To have your portrait done by Casas at that time was like what they used to say about Mario Testino: you’re not anybody until you’ve had your photograph taken by Testino.”

I ask whether the motivation for this kind of one-upmanship came from one generation’s seeking to supplant another, something one often sees in the history of art.

“The desire of the student to surpass the teacher? No doubt,” agrees Pinós. “In fact, in the memoirs of art critic Alfredo Opisso, he recalled how whenever Picasso came here, he always went and sat at the small table in the front room where Casas, Romeu, and the others always sat, so that he could see what they were up to. Not with his peers or with people his own age.”

“It’s also because he wasn’t really an ‘emerging talent,’” says Panyella, “like the other young artists who came here were. His work was already bearing fruit, which is something a lot more substantial than simply having the promise of bearing fruit. When you read art critics of the time like Opisso, they don’t talk about Picasso as an emerging talent on the scene. He’s already there.”

“Picasso becomes Picasso in part because of the people whom he chose to gather around him, and who then responded to his particular personality,” comments Pinós. Panyella adds, “I think another factor here is that realistically, Picasso wasn’t actually any sort of competition for these artists, from their perspective, and for his part he was so convinced of his own talent that they didn’t really bother him either. Plus, unlike Casas and Rusiñol, Picasso from the beginning didn’t experience the level of negative criticism from art publications in Barcelona and elsewhere.”

Picasso’s status as the most important artist of the twentieth century has been challenged in recent years by disputes not about his art, but over his personal life. This is, of course, a selective and contemporary form of outrage. No one seems to mind that Picasso, that evolutionary and revolutionary artist, shamelessly ripped off ideas from others to turn them to his own ends. No one cares that Picasso was a stereotypical champagne socialist, creating propaganda on behalf of Spain’s anti-clerical government or the French Communist Party, while simultaneously acquiring luxurious residences, antiques and art just like any other capitalist pig.

And speaking of the porcine, there is Picasso the user and abuser, leaving a trail of broken hearts and broken lives in his wake, as he moves on to his next romantic conquest without, in many cases, first bothering to properly sever his ties with the preceding one.

It is this aspect of Picasso’s biography that has gotten him into trouble in recent years. Unquestionably, Picasso mistreated people, particularly those with whom he was romantically involved. So now, fifty years after his death, does that means that Picasso should be “canceled”?

“What we can’t do here is to interpret our past history using the mentality of the twenty-first century,” Panyella comments. “I’m not in favor of ‘cancel culture,’ because it seems like a kind of backwardness and, frankly, a scam. I think Picasso was a tremendous wounder of women, like many other men. But he was not an exception, nor was he a predatory figure toward women. It’s a kind of false Puritanism; for an interpreter of Picasso’s work to blame the artist for all of these perceived sins doesn’t seem either intellectually correct or honest.”

I ask why so many art museums seem to have adopted the position that, in order to be relevant to today, they have to investigate and punish dead artists for their sins.

“This position on the part of museums has been induced,” she remarks. “And I’d like to know why. What I do see is that among museums today, they are taking on responsibilities for themselves, in a series of slogans and concepts. What interests me is to see what they’re going to do with our museums. Should we shut our museums? Should we only have one interpretation? Do we just take some things down? And if so, what? There are now many exclusions of art and artists from different periods — what purpose does this serve? To educate by only telling part of the story?”

“I think what we’re going through right now is a powerful cultural crisis,” she continues. “Because when you substitute understanding with activism, you end up with total cultural isolation and commercialism. What’s happened now is that we’ve moved from cultural activity to consumer culture. Right now, we are in the hands of profiteers. But the pendulum has swung too far in one direction, and now it’s going to have to start swinging back the other way. If as a museum you’re not actually educating the public, but engaging in activism, then to me you’ve just lost your purpose.”

As our very long lunch begin to wind down, I remark that Els Quatre Gats was a critically important place in art history: had Picasso not chosen to make it his local, who knows what the history of modern art might have been, or whether we would be talking about Picasso today?

Panyella agrees. “Picasso comes here, to this place, and says ‘I like this, I don’t like that. I’ll take some of this, and some of that.’ And all of it forms into something real in his work throughout his life. I think everything that he took with him from here, eventually comes together in his art.”

“It’s the foundation for Picasso’s development as an artistic figure,” Pinós asserts. “Picasso would not have become Picasso, if he had not gone to Paris. But he would never have even attempted to go to Paris, if it wasn’t for Els Quatre Gats.”

An exhibition exploring Picasso’s connections with Els Quatre Gats, featuring over 180 works of art, will be on view at the Museu del Modernisme in Barcelona from April 14 through July 14. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2023 World edition.