So much rap is outsourced id – music we play to put us in touch with deep animal parts of our inner lives, where we fight and fuck and flaunt our victories like civilisation never happened. The vast sums of money and creature comfort afforded to the play-actors are darkly poetic. Here’s the deal: you tell us about the grinding poverty, violence, drugs you came through and how you’re now rich as fuck, and we’ll make you so. Just pop out of your mansion every few months and remind us how the good life tastes when you’ve grown up hungry. We all want heedless, hedonistic triumph, but we’ll take it vicariously – we have jobs to hold down and mothers to please.

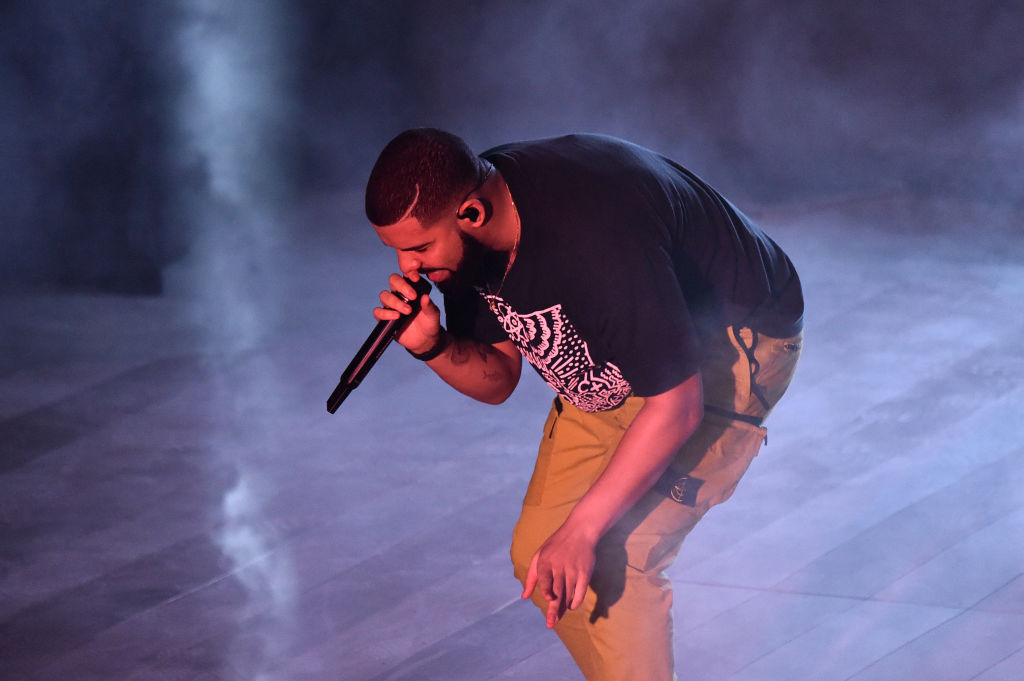

The Canadian rapper Drake has never been able to hold this street-hard pose for more than a second or two. It would look silly on him, even more than it does on the guys who’ve made their fortunes striking it over and over, long after they’ve retired into juice-cleanse domesticity. Drake is almost naked for the world to see: a sensitive, talented kid, a one-time soap opera star in Canada, pushing to place himself among the hard, triumphant men. He’s a tremendous performer and a phenomenal commercial success, largely because of his willingness to show himself soft too – sad, lonely at times, self-doubting. Like, for instance, a real person tends to be.

Drake’s had a few fine run-ins with the propped up statue-men of rap, the guys who pretend to be made of aggression, strength, and nothing soft at all. Competition is integral to rap, and sometimes that boils over into ad-hominem hostility. It’s part of the martial ritual that makes a lot of hip hop compelling. But Drake has never experienced a lyrical takedown as raw and cutting as the one delivered in May of this year by his long time rival, Pusha T. In a diss track titled “The Story of Adidon”, Pusha mocks Drake’s father, who left the home when Drake was five, and breaks the news that Drake has secretly fathered a young child with former porn star Sophie Brussaux, with whom he went on one or two dates while on tour:

You are hiding a child, let that boy come home Deadbeat mothafucka, playin’ border patrol

There have been devastating diss tracks before – Jay Z famously lost a battle with Nas in 2001 when Nas released “Ether”, a far, far better performance than Pusha’s halting, angry screed. Jay obviously came back, and Drake’s public has been wincing and waiting to see how Drake would respond. It was radio silence for weeks. On June 29, Drake released his fifth studio album, Scorpion, and it’s been occupying the number one spot on the billboard charts since then. It’s a good album, as Drake’s albums’ generally are. On the fourth track on Scorpion, titled “Emotionless”, Drake finally gets around to responding to Pusha:

I wasn’t hidin’ my kid from the world

I was hidin’ the world from my kid

From empty souls who just wake up and look to debate

Until you starin’ at your seed, you can never relate

Breakin’ news in my life, I don’t run to the blogs

The only ones I wanna tell are the ones I can call

They always ask,“Why let the story run if it’s false?”

You know a wise man once said nothin’ at all

Well, yes. That’s fair. Drake’s response is nimble and reasonable, utterly unflustered, explaining why he need not parade every bit of his life in front of the digital hordes. He makes music, and we pay him a fortune for it. Where in this arrangement does he oblige himself to disclose every painful detail of his romantic/sexual/reproductive life? We’ve all got our own private scandals, enough to keep us busy contemplating the agile human genius for fucking lives up, and hopefully putting them back together, with or without Drake, Sophie Bressaux, and their infant son Adonis.

This is all simple enough – Drake is a successful, intelligent guy who makes a mistake sometimes, and is cool and confident enough to know that he owes the internet no particular part of his pain. Except, no – this narrative is too easy, even if it’s the one Drake is selling on Scorpion. In interviews Drake is not the patient, calm, unflappable don he plays in his music. He’s a nervous, eager, agreeable kid, grateful to be here and tremendously ambitious. Hoping you like him as much as he wants to like you. There’s no way he was unfazed by Pusha T’s cruel, ungracious shank. He responded by waiting, and crafting a fine record composed, like all his records, of candid introspection and hyper-confident posing. He has to do the latter to play the game he’s chosen. The former has made him interesting. But Drake is not cool with this, it’s not easy and OK. I bet it hurts like hell.

That kind of pain has little place in hip hop, though; it’s a hard place to be broken and ashamed. Rap has traditionally emerged from communities already so afflicted. Its raison d’être precludes it from boldly exploring some important corners of the human experience. Be angry, yes – sure. But heartbroken and ashamed? That’s tougher. Those feelings will generally need to be sublimated, turned into something that will play well on meaner streets. Weakness gets your ass kicked.

Hip hop is ascendant now; it’s achieved a cultural influence its early practitioners couldn’t have imagined. Drake is one of the best we have at the moment, and he’s trying to broaden the emotional bandwidth of the genre, as are artists like Kendrick Lamar, Earl Sweatshirt, Tyler the Creator, and even, occasionally, Jay Z. It’s a noble attempt – lots of young people, especially young men, look to hip hop for models of how to be. Being a man is complicated and difficult. Drake seems to be wrestling, as best he can, with similar realities.

Ian Marcus Corbin is the owner of Matter & Light Fine Art in Boston, and a doctoral candidate in Philosophy at Boston College. Follow him on Twitter @ianmcorbin1